The unveiling today of the Hubble Ultra Deep Field, a spectacular new set of images from the Hubble Space Telescope, brings mixed emotions to astronomers at the University of California, Santa Cruz, who are trying to save the orbiting telescope from a premature end. While the Ultra Deep Field offers astronomers the deepest, most detailed view ever of the distant universe, it also underscores the unique capabilities that will be lost if the Hubble is allowed to die.

Congress is currently reviewing a NASA decision announced in January to cancel a planned servicing mission to the Hubble that would have extended its life past the end of the decade. Astronomers at UCSC and elsewhere have been outspoken in their support for the Hubble.

"The Hubble Space Telescope is the most successful telescope ever built and continues to be the centerpiece of worldwide astronomical research," said Sandra Faber, University Professor of astronomy and astrophysics. "Furthermore, Hubble is entering a new and even more productive phase in which bigger cameras enable it to map larger regions of the sky, storing away data on millions of stars and galaxies as a precious resource for future generations."

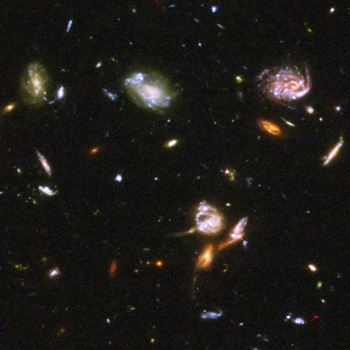

The Ultra Deep Field (UDF) is a deeper, more detailed version of the iconic Hubble Deep Field images obtained in 1995 and 1998. The UDF was acquired with a more powerful camera than the original deep field images, and more telescope time was devoted to it, enabling Hubble to capture light from the faintest and most distant objects ever observed. The results give scientists a view back to a time when the universe was just 5 percent of its present age, about 700 million years after the Big Bang.

"These results demonstrate how incredibly powerful the Hubble is. It is exploring some of the most interesting and important science questions of our day, and without it we won't be able to do these kinds of studies," said Garth Illingworth, professor of astronomy and astrophysics at UCSC.

Illingworth is deputy leader of the science team for the Advanced Camera for Surveys (ACS), one of two Hubble cameras used to obtain the UDF. He also helped plan the use of the Near Infrared Camera and Multi-Object Spectrometer (NICMOS) to image the same field. The combination of the two cameras--the ACS detecting optical wavelengths (visible light) and NICMOS detecting infrared wavelengths--gives astronomers a wealth of valuable data.

"Combining these images, we should be able to look back to within several hundred million years from the Big Bang and see if we can find galaxies in the earliest stages of their evolution," Illingworth said.

The ACS was installed on Hubble in 2002, and a new cooling system for NICMOS was installed during the same servicing mission. Additional instrument upgrades were planned for the servicing mission that is now slated for cancellation.

Only the Hubble Space Telescope can provide the extremely high resolution and wide field of view needed to obtain images like the UDF. Ground-based telescopes can obtain high-resolution images using adaptive optics technology, but adaptive optics works only over a tiny field of view, and it works only at much longer wavelengths of light, said Claire Max, professor of astronomy and astrophysics and deputy director of the Center for Adaptive Optics at UCSC.

"Using adaptive optics on the ground is like looking through a soda straw compared to Hubble's wide-angle lens," Max said.

Data from Hubble are used to guide the work astronomers do at ground-based observatories around the world, Illingworth said.

"When it comes to understanding galaxies--how they formed and evolved into galaxies like our own Milky Way--Hubble is at the center of a web, a large network of telescopes," he said. "Astronomers use the big telescopes on the ground to further explore objects detected by Hubble."

Hubble provides exquisitely detailed images of distant galaxies, showing their size and brightness and what kinds of stars they hold. Large ground-based telescopes, such as the Keck Telescopes, are needed to perform the spectroscopic analysis that can tell astronomers exactly how far away a galaxy is and other important properties. But without wide-field surveys like the UDF, astronomers wouldn't know where to point their giant ground-based telescopes to find those faint galaxies.

"It's an amazingly complementary activity. We can do so much more by using both together than we could ever do using ground-based telescopes alone," Illingworth said.

The original Hubble Deep Field image contained hundreds of tiny flecks and blobs of light that further analysis proved to be distant galaxies in the early stages of their evolution. But as deep as that image was, many of the most distant galaxies were extremely faint, and some were barely detectable. The UDF, with its higher resolution and wider field of view, is expected to reveal more distant objects in greater detail than astronomers have ever seen. (Details available at hubblesite.org/news/2004/07.)

"I expect the UDF to be as important as the original Hubble Deep Field has been in opening up new opportunities to study new objects, as well as objects we know about but don't yet understand," Illingworth said.

_____

Note to reporters: Illingworth will be in Baltimore at the Space Telescope Science Institute for the Hubble Ultra Deep Field Workshop for Science Writers on March 9. He will return to Santa Cruz on March 10, where he can be reached at (831) 459-2843 or gdi@ucolick.org. You may contact Faber at (831) 459-2944 or faber@ucolick.org.