Salt marsh restoration can mitigate flood risk and bolster community resilience to climate change in our local waterways, according to a recent study published in Nature by a postdoctoral fellow with UC Santa Cruz’s Center for Coastal Climate Resilience (CCCR).

The study, titled “The value of marsh restoration for flood risk reduction in an urban estuary,” explores the social and economic advantages of marsh restoration amidst the growing threats of sea level rise and storm-driven flooding. Climate change will put many communities at risk. In California, some of the study co-authors from the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) have shown that 675,000 people and $250 billion in property are at risk of flooding in a scenario with 2 m of sea level rise combined with a 100-year storm. Flooding due to sea-level rise is amplified by storms, which drive higher coastal water levels via surges, waves, and increased river discharge, along with increasing coastal population density.

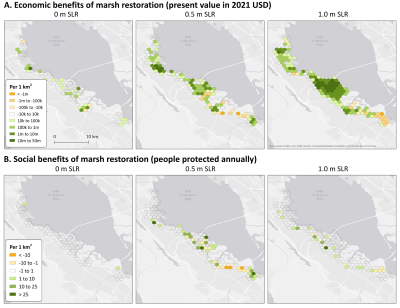

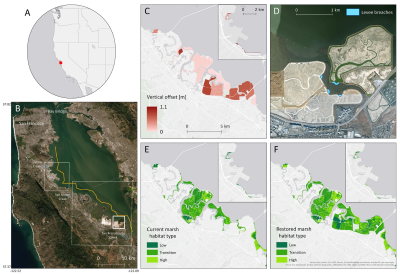

To simulate marsh restoration, the research team used a hydrodynamic model of San Francisco Bay, focusing on San Mateo County, the county most vulnerable to future flooding in California. The team ran computer simulations of the county’s shoreline during storms, with and without marsh restoration, and worked closely with local flood managers and planners to incorporate their input into the model.

“The Bay Area is low-lying and densely populated, thus at significant risk for future climate change impacts, and home to really large areas of degraded habitat. We have found compelling evidence that marsh restoration can reduce flood risk to people and property locally, providing both community and ecosystem co-benefits,” said CCCR fellow Rae Taylor-Burns, whose research also appears in a Springer Nature blog.

Key findings from the study include:

- Identification of priority areas in San Mateo County for salt marsh restoration to maximize socio-economic impacts in reducing flood risk.

- Development of a detailed flood model to evaluate the risk of flooding with and without salt marshes locally, aiding in the planning and design of restoration projects.

- The monetization of flood risk reduction benefits to identify cost-effective investments in marsh restoration, potentially attracting public and private funding.

The study underscores the broader implications of wetland restoration beyond flood protection, including carbon sequestration, habitat preservation, and recreational opportunities. It also makes the case for investments in nature-based solutions and community resilience that can help lessen future climate change impacts.

Researchers show the benefits of integrating salt marsh restoration into comprehensive climate resilience strategies in San Mateo County and estuaries worldwide that are facing similar threats. This could include funding from FEMA grant programs or Regional Measure AA, which provides approximately $500 million for marsh restoration throughout the San Francisco Bay. This work also supports identifying CA coastal wetlands as critical national infrastructure, as the Center has helped support coral reefs in Guam, Hawai’i, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands.

“As we confront the escalating challenges posed by climate change, it is imperative that we explore innovative solutions to enhance community resilience," said Michael W. Beck, director of the Center for Coastal Climate Resilience and a co-author of the study. “Salt marsh restoration represents a nature-based approach that can complement traditional infrastructure and safeguard our coastal communities."