Nearly a century on from the atrocities of World War II, the Japanese American experience is still not widely known. For many female-identifying activists, the chance to learn and reflect is now, to see how lessons from that time might still be relevant today.

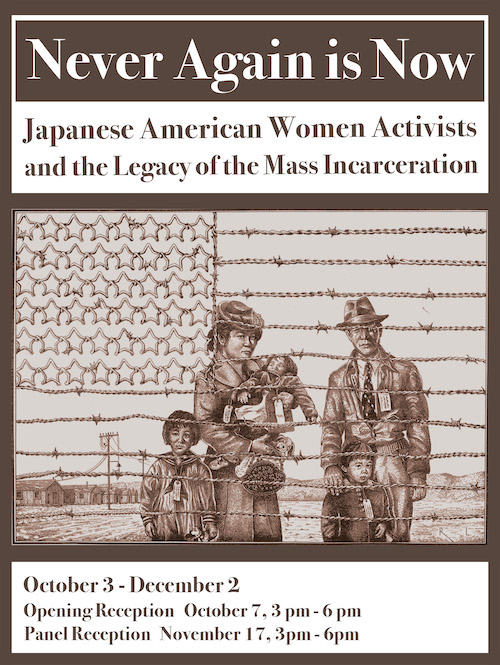

On Tuesday, Oct. 3, Cowell College’s Eloise Pickard Smith Gallery launched a two-month exhibition entitled “Never Again is Now: Japanese American Women Activists and the Legacy of the Mass Incarceration.” The exhibit — on display through Dec. 2 — features artwork and historical renderings of women’s memories surrounding this time period, including challenges to racial and gender stereotypes, promotions of intergenerational ties, and developed coalitions of years past.

The pieces include work from the women who were themselves affected during this dark period of history, as well as their daughters, granddaughters and non-binary family members.

History Department Chair and Co-Director of the Center for the Study of Pacific War Memories Alice Yang co-curated the exhibition after years of research into the topic. The exhibition was co-curated with the EPS new gallery curator, Martabel Wasserman, who invited local artists' contribution to compliment the exhibit. Yang, a second-generation Korean-American herself, has studied, researched and reported on the female Japanese-American experience dating back to the early 1990s, and published two texts on the topic with both Stanford University Press (2007) and Bedford/St Martin’s and Macmillan (2000).

This exhibition gives Yang and her collaborators the chance to continue those imperative conversations about this history, made ever more important by the fact that many who experienced this time period are passing away.

“The reason why this is important history to be studied is that it’s fundamentally a history that all Americans should know,” she explained. “For me, it’s not just about a war-time history; it’s also about the history of people’s scapegoating and fears after 9/11, it’s about the question of reparatory justice for other victims in the U.S. and outside the U.S., and includes victims of Japanese colonialism.”

One major topic of the exhibit is focused on the Redress Movement, which refers to Japanese American efforts to obtain the restitution of civil rights, an apology, and/or monetary compensation from the U.S. government. In 1978, the Japanese American Citizens League called on Congress to provide a restitution of $25,000 per internee, an apology, and funds toward an educational trust fund.

The Civil Liberties Act of 1988, signed into law by President Ronald Reagan, resulted in $20,000 in compensation — equivalent to $51,437 in 2023 — with a total of 82,219 redress checks.

Yang wrote a book, Historical Memories of Japanese American Internment and the Struggle for Redress, on the three different redress groups within the movement, showcasing how the experiences were remembered, still contested and still debated.

“All of that has continued to influence people’s perception of redress,” she said.

In the exhibit, Yang highlights Kathy Masaoka who has called on the US to support HR 40 and the African American community’s demand for reparations and has called on Japan to provide appropriate redress and apology to military sexual slaves of Imperial Japan, known as “comfort women.” Yang admires stories like hers and others throughout her curation and study of the movement.

“These activists have taken their experience from their family members, their experience of injustice, and argued that the lesson from that should be to support others who are unfairly targeted,” she said.

Further, Yang believes that studying this history allows current activists to recognize the wrongs of years past, and create a better future in times of strife.

“I fervently believe that it is important to understand in times of national security crisis like this, that there is a tendency for the government to scapegoat people they see as threats — and a lot of the time, that is based on unwarranted assumptions based on identity rather than behavior,” she said.

The exhibit hosted an opening reception on Saturday, October 7, and will host a panel reception open to the general public on Friday, November 17 from 3 to 6 p.m. Attendees are invited to register in advance for the event; more information is available via Cowell College.