Forty years ago, Craig Haney was a young professor of psychology at UC Santa Cruz when a question about the real causes of crime began to form in his mind: What if most violent criminal behavior is rooted in early childhood suffering, particularly the harrowing experiences of trauma, abuse, and maltreatment?

Haney had spent the day interviewing an inmate at San Quentin State Prison, and as he crossed the Golden Gate Bridge, he was struck by the consistent themes of abuse and deprivation that he'd heard during previous such interviews he’d conducted with men on Death Row.

Back on campus, Haney mentioned the patterns he was seeing to senior colleagues, who were skeptical. There wasn't much literature to suggest that early trauma could so profoundly shape adult behavior, and certainly not adult criminal behavior. There was an occasional suggestive study, but no solid database or convincing theory to support Haney's hypothesis.

What a difference four decades makes.

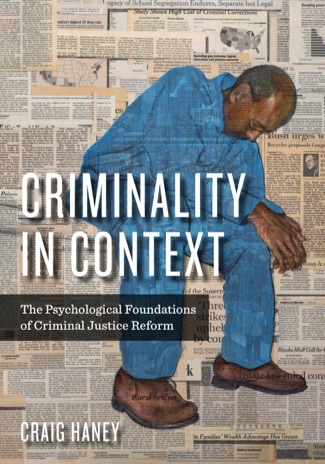

Haney, now a distinguished professor of psychology, is the author of the new book Criminality in Context: The Psychological Foundations of Criminal Justice Reform. The book is a comprehensive, in-depth analysis of 40 years of research into the root causes of criminal behavior. Haney's conclusions about the key role of preventable trauma and structural injustice also upend conventional thinking about how to bring about real reform in the criminal justice system.

"The nation’s dominant narrative about crime is that it is committed by bad people who freely choose to make bad decisions, persons who are fundamentally different from the rest of us" said Haney, who holds psychology and law degrees. "The only thing that is fundamentally different about them is the lives they’ve lived and the structural impediments they’ve faced."

Thousands of studies have been conducted since the day Haney took that fateful drive over the Golden Gate Bridge. They clearly establish that the people who are most at risk for criminal behavior are those who have been exposed to numerous traumas or “risk factors” in their lives, often beginning in childhood. The long-term impact of abuse and neglect is often compounded by additional mistreatment at the hands of the very institutions charged with protecting them, including schools, the foster care system, and the juvenile justice system, he said.

Haney's expertise on capital punishment and the psychological effects of incarceration have made him a leading voice in criminal justice reform. He has provided key testimony in major legal challenges regarding the death penalty, solitary confinement, and prison overcrowding. His previous books include Reforming Punishment: Psychological Limits to the Pains of Imprisonment, and Death by Design: Capital Punishment as a Social Psychological System.

"Poverty and race are intertwined in our society"

In addition, Haney argues, poverty and racism are major structural factors that contribute to crime. "Ninety percent of people in prison are poor, and the majority are people of color," said Haney.

Poverty is a “gateway” risk factor that exposes people to other forms of trauma, ensures a range of unmet needs, and can constrict opportunities over an entire life course, he said. Because race and poverty are so deeply intertwined in our society, people of color are more likely to confront these challenges. This fact, and their differential treatment at the hands of criminal justice system, accounts for their overrepresentation in our prisons.

If social, economic, and racial injustices are the real causes of criminal behavior, Haney argues, then the only real path to reducing crime is to meaningfully target them.

“Fundamental criminal justice reform will require us to change our conceptions of who commits crime and why," said Haney. "It isn't about individual pathologies. It's about pathological social histories and circumstances. We know this not because it's politically liberal or progressive to say so. We know it because there’s a mountain of data telling us it’s true."

If we don't change the narrative to align with hard scientific evidence, he said, genuine and lasting criminal justice reform is unlikely to ever succeed. Misplaced efforts like the War on Drugs in the 1980s and '90s exacerbated economic and racial inequality with policies that encouraged police departments to arrest and imprison more people, ushering in the era of mass incarceration that persists today.

Now, enlightened by scientific evidence and an overarching analysis of the causes of crime, Haney is advocating for "fundamental changes in the way we respond to crime and how we approach crime prevention." Both efforts—a much fairer set of legal responses and a more effective approach to prevention—must take adverse social histories and structural injustice into account, he said.

"Right now, death penalty cases are the only ones where a person’s background and circumstances are seriously considered in the sentencing process. Otherwise these things are largely excluded and ignored, and judges have very little latitude to take them into account," said Haney, who believes personal history and context are nonetheless relevant at every step of the adjudication process.

Similarly, to be effective, crime prevention strategies must focus on massive structural changes, including a serious effort to alleviate poverty.

"Addressing the terrible consequences of poverty and economic inequality is important in its own right, but also should be seen as advancing the goal of crime prevention," said Haney. "Reducing crime and poverty are part of the same social justice agenda."