Campus News

UC Santa Cruz: A dream preferred

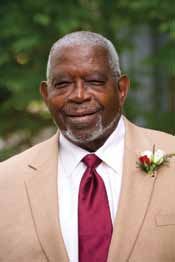

An essay by Oakes College founding provost J. Herman Blake about the transformative power of education.

Ed. note: As part of this year’s Alumni Reunion Weekend in April, emeritus writing lecturer Don Rothman and Oakes College founding provost J. Herman Blake sat down to talk about the transformative power of education. Their talk, which covered the importance of empathy and the enduring multicultural vision that guided the creation and growth of Oakes, moved many in the audience to tears. The following is an essay by Blake re-creating the talk.

When I joined the faculty of Cowell College in 1966, I thought my future path was clear and certain. My colleagues were young, hopeful, intelligent, and intellectual. They welcomed me into their company, and I felt privileged.

I could have stayed at Cowell forever. But deep inside me there was restiveness. Given my humble beginnings and the racial limits I had experienced in the years before UCSC, I felt ill at ease enjoying the boundless freedom of the present. I wanted to extend opportunity to many in the general community who would love to be where I was.

When Chancellor Dean McHenry asked me to partner with politics and community studies professor Ralph Guzman in planning a new college, I had my doubts. I had been on campus for just three years. My courses were just beginning to come together; while my research plans were dormant, my trajectory was academic scholarship, not administrative leadership. However, after counsel with Berkeley mentors, I accepted the invitation.

Ralph Guzman’s dreams for the Latino community paralleled mine for the African American community. We both agreed our plans should be wholly inclusive in spite of some community pressures to limit our focus.

We needed a core group of faculty to do the initial planning, so we carefully listed those on campus we knew shared our values and goals and sought them out.

When Oakes College opened in 1972, we still did not have a name, but I was satisfied with College VII. We had a small contingent of faculty and about 250 students. The faculty was a source of great comfort—incredible minds, great teachers, and totally committed to the university as well as the college.

There were about 20 or so minority students among that first group. Eventually we had a faculty that was about 30 percent women and 50 percent minority, many of them in the sciences.

Our goal of promoting the sciences among minority students began to take shape—and it was successful.

The doubts and fears that kept me awake at night, and often troubled my days, were eventually stilled by the visions, hopes, and dreams that soared into the stratosphere. Students who arrived with limited preparation responded well—they not only overcame, they prevailed.

They are now attorneys, teachers, social workers, physicians, entrepreneurs, and college professors.

In 2012 I was invited to spend a week at Oakes College in celebration of its 40th anniversary. I went to classes and seminars throughout the campus; met with faculty members, students, staff, and community members; and attended gatherings at the homes of the provosts of Oakes and Cowell colleges.

Having left UCSC in 1984 to assume the presidency of Tougaloo College in Mississippi, I had little understanding of the extraordinary changes in the college and the university. The chancellor, George Blumenthal, had been one of the original faculty in Oakes College. An astrophysicist, he was an outstanding teacher with a sensitive soul, and all students—particularly minority students—flourished in his classes. It was a huge change from 1972. Intellectual understandings we anxiously sought then were now intuitively understood.

Everywhere I went, it was like stepping into the middle of a dream.

There is no limit to what UCSC can become.

View the full talk between Blake and Rothman.