Archaeological exploration in sub-Saharan Africa is uncovering evidence that indigenous urban settlements existed hundreds of years ago and played a prominent role in the slave trade of the 17th through 19th centuries.

J. Cameron Monroe, an assistant professor of anthropology at UC Santa Cruz, details his findings from more than a decade of field survey and digging in the west African republic of Bénin. His article, "Urbanism on West Africa's Slave Coast" in the September/October 2011 edition of American Scientist, shows how archaeology "plays an important role in rejecting the idea that Africa has never been more than a recipient of cultural stimulus from the outside world."

Monroe's research builds on work in the 1980s and 1990s by Susan and Roderick McIntosh in Mali who demonstrated that urban settlements existed in the Niger delta region more than 1,000 years ago. Monroe said they were the first to debunk the notion that large-scale settlements existed only after contact with outside cultures.

"The McIntoshes documented a deep history of urbanism and shook the field up," he said. West Africa is a region where "we not only didn't know much but what we thought we knew was increasingly disproven," he said.

Monroe's research focuses on settlements–cities or kingdoms–that emerged in the era of European contact. He wants to understand how Atlantic commerce affected the nature of urban-area formation and urban-rural relations. He calls his quest the "Abomey Plateau Archeological Project" and has been working on it since 2000. Two years ago he led a research expedition that included UCSC undergraduates.

Monroe said the biggest surprise came early in the research as he and colleagues tracked the distribution of royal palace sites. He was surprised at how extensive and interconnected they were.

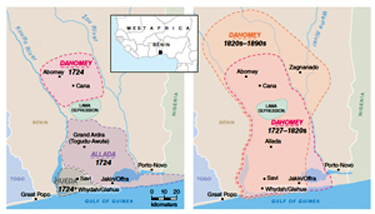

As colonizing Europeans began establishing outposts during the 16th and 17th centuries, the native societies began to change and adapt, Monroe said. As the slave trade grew in the second half of the 17th century, West African urban communities transformed. "Royal capitals expanded rapidly, towns emerged on the coast and in the interior, and people flocked to the European-controlled coastal fortresses," he writes.

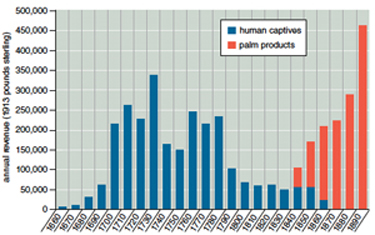

The existing societies made a living from the slave trade as they facilitated the transfer of Africans from the interior to slave ships on the coast.

As the slave trade slowed in the 19th century, commerce in palm oil, sought by European countries, grew, he said. That ushered in profound societal changes because nearly "anyone with a pot and a palm tree became an active participant in Atlantic trade." Royal dynasties that existed for centuries were forced to change.

Monroe, who was last in Benín a year ago, is currently working on funding proposals for a three-year project to complete his research. One aspect will be further field research opportunities for undergrads and graduate students.

Archaeology probes West African cities and impact of European influence

Shift from trade in human captives to palm oil changed social and power relationships