Campus News

UCSC astronomers find most distant galaxy candidate yet seen

Astronomers have found what may be the most distant galaxy ever seen, about 13.2 billion light-years away.

STIFF image

Astronomers studying ultra-deep imaging data from the Hubble Space Telescope have found what may be the most distant galaxy ever seen, about 13.2 billion light-years away. The study pushed the limits of Hubble’s capabilities, extending its reach back to about 480 million years after the Big Bang, when the universe was just 4 percent of its current age.

“We’re getting back very close to the first galaxies, which we think formed around 200 to 300 million years after the Big Bang,” said Garth Illingworth, professor of astronomy and astrophysics at the University of California, Santa Cruz.

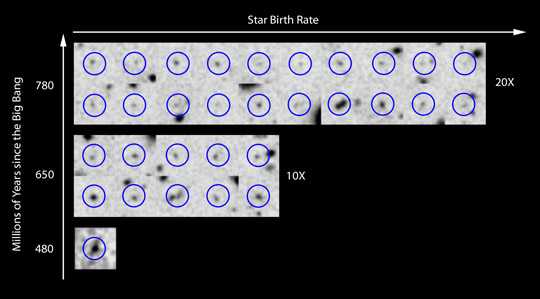

Illingworth and UCSC astronomer Rychard Bouwens (now at Leiden University in the Netherlands) led the study, published in the January 27 issue of Nature. Using infrared data gathered by Hubble’s Wide Field Planetary Camera 3 (WFC3), they were able to see dramatic changes in galaxies over a period from about 480 to 650 million years after the Big Bang. The rate of star birth in the universe increased by ten times during this 170-million-year period, Illingworth said.

“This is an astonishing increase in such a short period, just 1 percent of the current age of the universe,” he said.

There were also striking changes in the numbers of galaxies detected. “Our previous searches had found 47 galaxies at somewhat later times when the universe was about 650 million years old. However, we could only find one galaxy candidate just 170 million years earlier,” Illingworth said. “The universe was changing very quickly in a short amount of time.”

According to Bouwens, these findings are consistent with the hierarchical picture of galaxy formation, in which galaxies grew and merged under the gravitational influence of dark matter. “We see a very rapid build-up of galaxies around this time,” he said. “For the first time now, we can make realistic statements about how the galaxy population changed during this period and provide meaningful constraints for models of galaxy formation.”

Astronomers gauge the distance of an object from its redshift, a measure of how much the expansion of space has stretched the light from an object to longer (“redder”) wavelengths. The newly detected galaxy has a likely redshift value (“z”) of 10.3, which corresponds to an object that emitted the light we now see 13.2 billion years ago, just 480 million years after the birth of the universe.

“This result is on the edge of our capabilities, but we spent months doing tests to confirm it, so we now feel pretty confident,” Illingworth said.

The galaxy, a faint smudge of starlight in the Hubble images, is tiny compared to the massive galaxies seen in the local universe. Our own Milky Way, for example, is more than 100 times larger.

The researchers also described three other galaxies with redshifts greater than 8.3. The study involved a thorough search of data collected from deep imaging of the Hubble Ultra-Deep Field (HUDF), a small patch of sky about one-tenth the size of the moon. During two four-day stretches in summer 2009 and summer 2010, Hubble focused on one tiny spot in the HUDF for a total exposure of 87 hours with the WFC3 infrared camera.

To go beyond redshift 10, astronomers will have to wait for Hubble’s successor, the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), which NASA plans to launch later this decade. JWST will also be able to perform the spectroscopic measurements needed to confirm the reported galaxy at redshift 10.

“It’s going to take JWST to do more work at higher redshifts. This study at least tells us that there are objects around at redshift 10 and that the first galaxies must have formed earlier than that,” Illingworth said.

Illingworth’s team maintains the First Galaxies web site, with information about the latest research on distant galaxies.

In addition to Bouwens and Illingworth, the coauthors of the Nature paper include Ivo Labbe of Carnegie Observatories; Pascal Oesch of UCSC and the Institute for Astronomy in Zurich; Michele Trenti of the University of Colorado; Marcella Carollo of the Institute for Astronomy; Pieter van Dokkum of Yale University; Marijn Franx of Leiden University; Massimo Stiavelli and Larry Bradley of the Space Telescope Science Institute; and Valentino Gonzalez and Daniel Magee of UC Santa Cruz.

This research was supported by NASA and the Swiss National Science Foundation.

The new Hubble results show that the rate of star birth changed dramatically in the universe over just 170 million years, increasing by ten times from 480 million years after the Big Bang to 650 million years, and doubling again in the next 130 million years, as shown schematically in this bar graph. The astonishing 10 times increase in star birth happened in a period that is just 1 percent of the current age of the universe. Credit: NASA, ESA, Garth Illingworth (UC Santa Cruz), Rychard Bouwens (UC Santa Cruz and Leiden University) and the HUDF09 Team.