Scientists once thought that life could originate only within a solar system's "habitable zone," where a planet would be neither too hot nor too cold for liquid water to exist on its surface. But according to planetary scientist Francis Nimmo, evidence from recent NASA missions suggests that conditions necessary for life may exist on the icy satellites of Saturn and Jupiter.

"If these moons are habitable, it changes the whole idea of the habitable zone," said Nimmo, a professor of Earth and planetary sciences at UC Santa Cruz. "It changes our thinking about how and where we might find life outside of the solar system."

Nimmo discussed the impact of ice dynamics on the habitability of the moons of Saturn and Jupiter on Tuesday, December 15, at the annual meeting of the American Geophysical Union in San Francisco.

Jupiter's moon Europa and Saturn's moon Enceladus, in particular, have attracted attention because of evidence that oceans of liquid water may lie beneath their icy surfaces. This evidence, plus discoveries of deep-sea hydrothermal vent communities on Earth, suggests to some that these frozen moons just might harbor life.

"Liquid water is the one requirement for life that everyone can agree on," Nimmo said.

The icy surfaces may insulate deep oceans, shift and fracture like tectonic plates, and mediate the flow of material and energy between the moons and space.

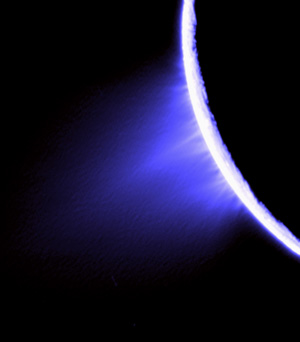

Several lines of evidence support the presence of subsurface oceans on Europa and Enceladus, Nimmo said. In 2000, for example, NASA's Galileo spacecraft measured an unusual magnetic field around Europa that was attributed to the presence of an ocean beneath the moon's surface. On Enceladus, the Cassini spacecraft discovered geysers shooting ice crystals a hundred miles above the surface, which also suggests at least pockets of subsurface water, Nimmo said (see earlier story).

Liquid water isn't easy to find in the cold expanses beyond Earth's orbit. But according to Nimmo, tidal forces could keep subsurface oceans from freezing up. Europa and Enceladus both have eccentric orbits that bring them alternately close to and then far away from their respective planets. These elongated orbits create ebbs and flows of gravitational energy between the planets and their satellites.

"A moon like Enceladus is getting squeezed and stretched and squeezed and stretched," Nimmo said.

The extent to which this squeezing and stretching transforms into heat remains unclear, he said. Tidal forces likely shift plates in the lunar cores, creating friction and geothermal energy. This energy may also rub surface ice against itself at the sites of deep ice fissures, creating heat and melting, according to Nimmo. Enceladus's geysers appear to originate from these shifting faults, and the thin lines running along Europa's surface suggest geologically active plates, he said.

A frozen outer layer may be crucial to maintaining oceans that could harbor life on these moons. The icy surfaces may shield the oceans from the frigidity of space and from radiation harmful to living organisms.

"If you want to have life, you want the ocean to last a long time," Nimmo said. "The ice above acts like an insulating blanket."

Enceladus is so small and its ice so thin that scientists expect its oceans to freeze periodically, making habitability less likely, Nimmo said. Europa, however, is the perfect size to heat its oceans efficiently. It is larger than Enceladus but smaller than moons such as Ganymede, which has thick ice surrounding its core and blocking communication with the exterior. If liquid water exists on Ganymede, it may be trapped between layers of ice that separate it from both the core and the surface.

The core and the surface of these moons are both potential sources of the chemical building blocks needed for life. Solar radiation and comet impacts leave a chemical film on the surfaces. To sustain living organisms, these chemicals would have to migrate to the subsurface oceans, and this can occur periodically around ice fissures on moons with relatively thin ice shells like Europa and Enceladus. Organic molecules and minerals may also stream out of their cores, Nimmo said. These nutrients could support communities like those seen around hydrothermal vents on Earth.

Nimmo cautioned that being habitable is no guarantee that a planetary body is actually inhabited. It is unlikely that we will find life elsewhere in our solar system, despite all the time and resources devoted to the search, he said. But such a discovery would certainly be worth the effort.

"I think pretty much everyone can agree that finding life anywhere else in the solar system would be the scientific discovery of the millennium," Nimmo said.