The legendary "man-eating lions of Tsavo" that terrorized a railroad camp in Kenya more than a century ago likely consumed about 35 people--far fewer than popular estimates of 135 victims, according to a new analysis led by researchers at the University of California, Santa Cruz. The study also yields surprises about the predatory behavior of lions.

Despite the notoriety of the attacks--the harrowing nine-month saga has been the subject of three Hollywood films, and the lions remain a popular exhibit at the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago--the number of victims has been a matter of dispute. The new study, "Cooperation and Individuality Among Man-Eating Lions," appears in the Nov. 2 issue of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. The research utilized a sophisticated stable-isotope analysis to investigate this vexing question.

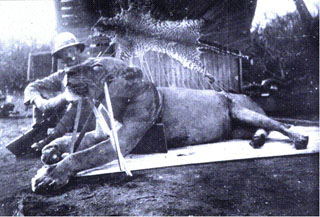

By analyzing samples of the hair and bone of the lions, researchers were able to estimate that one lion likely ate 11 humans and the other consumed 24 people during the animals' final nine months. Both lions were shot and killed in December 1898 by Lt. Col. John H. Patterson, a British officer and engineer hired to restore safety in the region. For years after, Patterson, who gained great notoriety for the feat, claimed the lions had killed 135 people--far more than the Ugandan Railway Company's estimate of 28 victims.

"This has been a historical puzzle for years, and the discrepancy is now finally being addressed," said Nathaniel J. Dominy, an associate professor of anthropology at UCSC. "We can imagine that the railroad company might have had reasons to want to minimize the number of victims, and Patterson might have had reasons to inflate the number. So who do you trust? We're removing all those factors and getting down to data."

Dominy and lead author Justin D. Yeakel, a doctoral candidate in ecology and evolutionary biology at UCSC, collaborated on the project with Bruce D. Patterson, the MacArthur Curator of Mammals at the Field Museum (no relation to John H. Patterson).

To investigate each lion's lifetime dietary patterns, Yeakel analyzed samples of their bone collagen and hair keratin that were provided by the Field Museum. He then compared those data to the isotopic signatures of the lions' presumptive prey, including modern grazing and browsing animals, and humans. Human samples were obtained from the remains of Kenya's Taita population that were gathered by anthropologist Louis Leakey during his famous East African Archaeological Expedition of 1929.

The results suggest that during the final months of what John Patterson described as the lions' "reign of terror," fully half of one lion's diet consisted of humans, with the balance made up of mid-sized grazing animals such as gazelles and impala. Strikingly, the other lion ate very few humans, subsisting instead on herbivores. That dietary disparity leads Dominy and Yeakel to infer that the Tsavo lions worked together to scatter everyone, both humans and wild game, setting the stage for one to gorge on humans and the other to feed on herbivores.

"The idea that the two lions were going in as a team yet exhibiting these dietary preferences has never been seen before or since," said Dominy.

Cooperative hunting is beneficial when lions are stalking large prey like Cape buffalo and zebra, but humans are small enough that lions don't typically need to work together to make a kill. In this case, an array of conditions may have temporarily altered the lions' behavior, including drought and disease that depleted the availability of the lions' conventional prey. In addition, large numbers of people and animals had gathered for the railroad project, and severe dental problems and a jaw injury suffered by one of the lions probably greatly inhibited its ability to hunt.

"These findings underscore the complexity of what lions are capable of doing, and the complex interplay of costs and benefits that determine the size of their coalitions," he said.

The stark dietary differences highlight the importance of considering individuals within populations, said Yeakel. "In ecology, we often think of a population as being the sum of its parts, but there can be really rich things happening among individuals in a population," he said. "It's a new way of thinking about how populations work to consider how individuals affect the whole."

More than a century after the attacks, the Tsavo lions remain notorious; last year, the National Museum of Kenya began an effort to recover the remains of the lions, saying they represent an important part of the country's history and heritage. The grisly chapter finally ended in December 1898, when John Patterson--after nine months spent in pursuit of the animals--shot and killed one lion, then killed the second lion 20 days later. During the final three months of the nine-month siege, lion attacks were a "nightly occurrence," and work on the railroad expansion had ground to a halt as terrified laborers refused to work, said Dominy, noting that the delay prompted the first and only mention of lions in Britain's House of Parliament as members demanded an explanation for the work stoppage.

Ending the terror earned John Patterson widespread and enduring fame, but Dominy wonders if the boastful hunter might have exaggerated his estimate of victims to enhance his own reputation. "The railroad company attributed the deaths of 28 Indian nationals to the lions, and Patterson may have reasonably assumed scores of Africans were also killed," said Dominy. "But based on our statistical analysis, there's an outside chance they ate as many as 75 people. Our evidence attests only to the number of people eaten, not the number of people killed."

In 1924, John Patterson sold the hides of the lions--which he had used as rugs--to the Field Museum, where taxidermists restored and stuffed the pelts and mounted a diorama that continues to fascinate museum visitors today. Patterson's 1907 book, The Man-Eaters of Tsavo, was an international bestseller when it was published, and it remains in print today.

"The fact that we can determine both the diet and the behavior of two animals killed more than a century ago is a testament to the enduring value of museum collections and the science that interprets them," said Field Museum curator Bruce Patterson. "The rather extravagant claims (Colonel) Patterson made in his book can now be pretty much dismissed."

For Dominy, downgrading the number of human victims of the Tsavo lions is the latest chapter in a legend that takes a new turn with the insights about lion predation offered by these animals. The path of human evolution has been shaped by predation, said Dominy, noting that the efficiency benefits of bipedalism are gained at the cost of speed, making humans vulnerable to quick, four-legged predators, including lions.

"In a discussion of bipedalism, Louis Leakey once said, 'People are not cat food,' " said Dominy. "But they are. This study proves that."

In addition to Dominy, Yeakel, and Bruce Patterson, coauthors on the paper are Kena Fox-Dobbs, assistant professor of geology at the University of Puget Sound; Mercedes M. Okumura, research curator in human evolutionary anatomy at the Leverhulme Centre for Human Evolutionary Studies at the University of Cambridge; Thure E. Cerling, distinguished professor of biology and of geology and geophysics at the University of Utah; Jonathan W. Moore, assistant professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at UCSC; and Paul L. Koch, professor of earth and planetary sciences at UCSC.

#####

Note to journalists: Dominy may be reached at (831) 459-2541 or njdominy@ucsc.edu; Yeakel may be reached at (831) 704-6218 or via e-mail at jyeakel@pmc.ucsc.edu; Bruce Patterson may be reached at (312) 665-7750, via e-mail at bpatterson@fieldmuseum.org, or through Nancy O'Shea, director of public relations at The Field Museum, at (312) 665-7103 or via e-mail at noshea@fieldmuseum.org.