At the beginning of her first quarter at UC Santa Cruz, freshman biology student Kimberly Davis collected some soil from the forest floor near Thimann Labs. She then isolated a bacterial virus from the soil, took pictures of it with an electron microscope, extracted the virus's DNA, sent it off for sequencing by the national laboratories' Joint Genome Institute, and is now analyzing the DNA sequence and studying the virus's genes.

It's all part of the Phage Genomics Lab course, in which a select group of students get to dive straight into research, while also taking the usual introductory biology lectures. Davis and her 13 classmates are making real contributions to scientific understanding of the genetic diversity of bacterial viruses (also known as bacteriophages or phages). Ultimately, they plan to publish their findings in a scientific journal.

"It's a really innovative way to learn and a great introduction to science," Davis said. "This is real research, discovering things that people don't already know, and that's really cool."

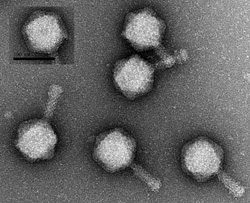

Bacteriophages are viruses that infect bacteria. They are so widespread that they are thought to kill off a significant fraction of the bacteria on the planet every day, said Grant Hartzog, associate professor of molecular, cell and developmental (MCD) biology. Because of their abundance and diversity, they represent one of the largest reservoirs of genetic diversity on the planet.

"When the students isolate their own virus, they are guaranteed to find something new," Hartzog said.

Students in the class isolated phages from locations all over campus, including the Alan Chadwick Garden, the Arboretum, and the Pogonip. The phage isolated by Davis infects a benign soil bacterium (related to the tuberculosis bacterium, although it does not cause disease). She named it "Little Red Riding Hood" in recognition of its forest origins. It has a large genome for a bacteriophage, consisting of about 150,000 base pairs of DNA that encode more than 200 genes.

"It's been a lot of work. I spent a lot of my free time in the lab, but it's really fun to see the results, and knowing that we'll write a paper about it is very gratifying," Davis said. "I think most of us in the class have decided we want to continue to do scientific research."

Hartzog said the course has clearly succeeded in getting students excited and engaged in their studies. It also prepares students for research in faculty labs and provides concrete examples of many of the principles that they learn in their lecture courses.

"We want to get them involved in research as early as possible in their college careers to enrich the quality of their experience here and give them the best chance for success after they leave," Hartzog said.

The course is funded for three years by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI), which is sponsoring similar lab courses at 12 institutions around the country as part of the Science Education Alliance. At UCSC, Hartzog teaches the lab together with Manuel Ares, professor of MCD biology.

"It's a problem-solving class. They have a task to do and they learn by doing," Ares said.

Ares and Hartzog selected the students for the class after inviting applications from incoming freshmen with strong backgrounds in high school biology.

"When you have a curriculum that's designed to serve a very heterogeneous mix of students, the more accomplished students can end up feeling neglected. We have to work harder to keep those students engaged," Ares said. "The way most practicing scientists know facts is by the experiments that prove them, and this course provides an experimental context that is absent from most lecture classes."

The HHMI funding paid for the sequencing of only one phage genome, so Davis was thrilled when hers was chosen. Hartzog subsequently obtained a grant from the California Institute for Quantitative Biosciences (QB3) that paid for the sequencing of all the other phages isolated by the class.

Ares has created a web-based Phage Genome Browser that the students use to analyze the viral DNA sequences. The browser, which provides a variety of tools for studying genome sequences, is based on the widely used UCSC Genome Browser created and maintained by researchers at the Center for Biomolecular Science and Engineering.

"We've learned a lot about sequencing and sequence analysis. It takes awhile to realize how much information there is in the browser," said student Jessica Ruby.

Ares and Hartzog plan to build on their experiences with this course to provide similar opportunities for a larger number of students and faculty.

"The lab may eventually evolve into a series of one-quarter courses that would involve more students," Hartzog said. "We can also create other courses, such as a bioinformatics course that would focus on analyzing the novel sequence data we are acquiring. The idea is to use this as a catalyst to create other fun and interesting teaching and learning opportunities on campus."