Like a marketer's dream come true, Americans have responded to environmental hazards by shopping, as if buying bottled water and organic vegetables will protect them and their loved ones.

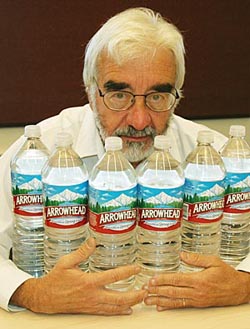

But "buying green" offers little real defense against environmental degradation and may pose an even greater threat by lulling people into a false sense of security, according to sociologist Andrew Szasz, author of the new book Shopping Our Way to Safety: How We Changed from Protecting the Environment to Protecting Ourselves.

"It's a peculiar form of environmentalism in which people recognize the problem but have given up on any hope of collective improvement," said Szasz, a professor of sociology at the University of California, Santa Cruz. "Consumers believe these products will protect them, which creates a kind of political anesthesia and precludes the collective action that generates real change."

In his book, Szasz documents the widespread popularity of products designed to protect consumers from environmental threats, critiques their effectiveness, and describes the unintended political consequences of a populace eager to "shop their way out of harm's way."

Sales of bottled water have soared amidst public concern over the safety of tap water, and consumers readily pay roughly 1,000 times as much for bottled water as they would pay for the same amount of tap water, says Szasz. But what are they getting for their money? Bottled water is less stringently regulated than tap water, according to Szasz. And although people who consistently eat organic foods do have lower levels of pesticide residues in their bodies, they are not residue-free. As for "natural" personal hygiene products, "nontoxic" household cleaning products, "natural" clothing, bedding, and furniture, Szasz points out that these products are poorly regulated, if they are regulated at all.

"These products do not work nearly well enough to warrant the faith consumers have placed in them," said Szasz, who calls this individualistic, consumer-based approach to protection "inverted quarantine." He likens the phenomenon to the fallout shelter panic of 1961, when Americans briefly embraced the notion that they could survive a nuclear attack in a backyard shelter. For a few months, until people accepted the fact that such shelters would fail--and tensions with Russia eased--the nation was in the throes of a frenzy that illuminates "the ultimate limits of individual self-protection," according to Szasz. The shelter panic is an extreme example of inverted quarantine, but the dynamics today are similar, he said.

"Rather than trying to limit the presence of contaminants in our environment, people are trying to keep contaminants out of their bodies," said Szasz. "It's a very fatalistic approach, and it is only an option for those who can afford to buy bottled water, organic food, and all the other putative shields available in today's marketplace."

Because consumers place such high levels of faith in these products, they feel far less compelled to support, or participate in, efforts to actually clean up the environment, said Szasz, author of Ecopopulism: Toxic Waste and the Movement for Environmental Justice (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1994).

"People feel vulnerable, and rightly so, but instead of engaging in political action, they respond by trying to barricade themselves from environmental hazards," he said. "By shopping, they think they've solved the problem. It's a form of political anesthesia, and it's really the opposite of what environmentalism is all about."

Although surveys show that Americans overwhelmingly want clean air and clean water, environmental policy hasn't risen to the top tier of issues on voters' minds for years, a disconnect that Szasz attributes to their belief that they have successfully purchased protection for themselves and their families.

"Consumers don't get the protection they think they're buying, which is a problem for the individual," said Szasz. "The problem for society is that their false belief produces political anesthesia."

But environmental threats are real, and they are likely only to intensify, warned Szasz, who hopes public awareness of the inverted quarantine effect will rouse people from their complacency and rekindle a more vibrant, collective environmental movement. "But that will happen only if Americans reject the mirage of individual solutions to our collective plight," he concluded.

------------

Note to reporters: Szasz may be reached at (831) 459-2653 or via e-mail at szasz@ucsc.edu.