When National Geographic hired Kennan Ward to photograph red tree-kangaroos, he was thrilled by the prospect of a trip to Australia. His joy quickly turned to disappointment, however, when the magazine sent him to the San Diego Wild Animal Park to shoot captive animals.

"Even for the biggest magazines, it's just not cost-effective to photograph animals in the wild," said Ward, one of the leading wildlife photographers in the world and a purist who prefers to work in nature. "I like my animals wild. That's what separates us from 99 percent of the nature photography out there."

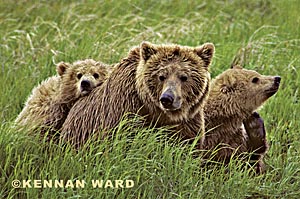

Ward, who earned a B.A. in environmental studies and wildlife biology from UC Santa Cruz in 1980, and his wife and fellow photographer, Karen, have spent three decades crisscrossing the globe to photograph animals in the wild. Ward is perhaps best known for his captivating photographs of grizzly bears, although his portfolio includes stunning landscapes and irresistible shots of polar bears, birds, marine mammals, and more. His success has allowed Ward to pursue his art on his own terms: He and Karen spend three to six months each year in the field and have logged hundreds of hours in Alaska, Antarctica, and Africa.

The author of six books, including books about grizzlies, polar bears, Denali National Park, and the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, Ward is a naturalist as well as a documentarian.

Ward credits his UCSC mentor, the late Raymond Dasmann, with broadening his understanding of bears by encouraging him to learn about natural history, ecology, and habitat. "That's the best thing I learned at UCSC--natural history," said Ward, producing a copy of his hand-typed senior thesis "Grizzly Bears and Man (A Co-Evolution)." Dasmann, with fellow environmental studies professor Richard Cooley and natural history professor Kenneth Norris, were "the best in the world," said Ward. "It was an incredible opportunity to absorb from those guys, who were at the top of their game."

With so much experience photographing and observing grizzly bears in Alaska, Ward saw an opportunity six years ago to reach viewers on another level and began filming bears in the wild. Ward's first-ever feature-length documentary film, Making Tracks, tells the story of two Alaskan grizzly bear cubs.

"Knowing so much about bear biology and behavior, I find still photographs don't show me their full behavior," said Ward. "I love still photography, because you can capture a moment and store it, but motion goes one step beyond. It gives you more emotion."

Narrated by Ward, the film showcases the photographer's signature themes that run through his books: challenge, competition, and the struggle for survival. Appropriate for children and engaging for adults, the 100-minute film showcases grizzlies like never before.

"It shows the life of two cubs with their mother for three years," said Ward, who spent six months poring through hundreds of hours of tape with editor Matt Widmann. "This is the real thing. It's natural history."

Ward has little regard for what he calls a "touchy-feely" approach to documenting animal behavior, in which humans make themselves and their interactions with animals part of the story. "This was going to be a rebuttal to Grizzly Man," said Ward, referring to Werner Herzog's documentary about Timothy Treadwell's years living among grizzlies in Alaska. "But then all of the sudden I realized the cubs had a story of their own, and their story unfolded."

Making Tracks shows the cubs foraging for food, learning to snag salmon, being harassed by coyotes, and it features many other behaviors that enlighten and entertain.

"The cubs face all kinds of trouble," said Ward. "What I like is that we, as kids and adults, are always in trouble, just like the cubs. But the cubs keep on going. They're a good example for us."

Ward treasures his time in the remote wilderness, where he keeps his distance from the subjects he is photographing. "Every single moment I'm in nature, I learn something," he said. "It's humbling."

Few people have the patience and determination to do what the Wards do, however. Karen said a typical day in Alaska begins with coffee at 3 a.m., followed by several hours in the field. By 7:30 a.m., the light is too bright and the photographers retreat for a midday nap, only to rise at 4 p.m. and shoot again until midnight. "You work seven days a week and never sleep eight hours in a row," she said. "You're pretty much on call the whole time. You can spend months waiting, and then something happens for two minutes. If you miss it, you're heartbroken."

The difference between a good shot and a great shot is timing, she said, adding that many summers they've had "fourth quarter" success. One summer, on the very day the plane was coming to pick them up from their remote location, the caribou migration began, with 180,000 animals moving through in a few hours. "Kennan shot 10 rolls," she recalled. "That made our whole summer."

Ward grew up in the Midwest, moved to California by himself at the age of 19, and put himself through school working as a park ranger. "I wasn't supposed to go to college, but I was really curious," he said. Awed by the beauty of California, he started taking photographs in earnest to show his family and friends what he'd found. "I couldn't believe it," he recalled. "Photography was my only tool to describe this place."

Three decades later, UCSC undergraduates in environmental studies and biology regularly intern with the Wards in their Santa Cruz-based business. "As you get older, you have a need to help somebody on their way," he said. "Ray Dasmann did that for me."

Ward's images are available on note cards, on posters, and in limited edition fine-art prints from Kennan Ward Photography. "I'm a surviving artist," said Ward. "I'm one of a handful who has the freedom to do this. We have the luxury of time and our own resources."

Ward's next project draws on the wisdom of his mentor. "Ray always said, 'If you want to know the predator, watch the prey.' So I'm going to do salmon. It involves all my pals--foxes, wolves, otters, eagles, orcas, seals, and bears."