An international team of scientists will investigate how water flows through rock formations beneath the seafloor during an eight-week expedition this summer to the eastern flank of the Juan de Fuca Ridge off the coast of British Columbia. It will be the first expedition of the Integrated Ocean Drilling Program (IODP), an ambitious new international collaboration set up to succeed the Ocean Drilling Program (ODP), which supported 20 years of international expeditions to study the ocean floor and obtain evidence of Earth's history from seafloor sediments.

Andrew Fisher, professor of Earth sciences at the University of California, Santa Cruz, is co-chief scientist of this first IODP expedition, along with Tetsuro Urabe of the University of Tokyo.

The amount of water that circulates through the upper oceanic crust is equivalent to the combined flows of all the rivers that pour off of the continents, Fisher said. Driven by slight differences in temperature and pressure within the seafloor, this "hydrothermal flow" is enough to recirculate all of the water in the oceans through the seafloor every few hundred thousand years, he said.

"This process affects the chemistry of the ocean, changes the properties of the crust itself, and influences the microbial communities that live below the seafloor," Fisher said. "We know it's important, but we really don't understand much about how it works."

The researchers will be drilling holes deep into the seafloor and capping the holes with elaborate structures called "CORKs" that will enable scientists to monitor processes beneath the seafloor and conduct experiments. These advanced seafloor observatories allow measurements of temperature, pressure, fluid chemistry, and microbiology to be obtained from different depths in the borehole. The CORKs, which stand about two stories high on the ocean floor, cap boreholes that extend hundreds of meters through the seafloor sediments and into the "basement rocks," the basalt of the upper oceanic crust. One function of the CORKs is to allow conditions within the boreholes to equilibrate.

"When you drill the hole, you change the temperature and the pressure and you contaminate things, and the only way to get back to equilibrium is to seal it up and let it sit for awhile," Fisher explained. "The CORKs basically plug the hole. They also have lots of valves and connections where we can hook up to them with a submarine or an ROV [remotely operated vehicle] and take measurements from different intervals in the borehole."

The researchers plan to put in four observatories this summer. The observatories will enable them to conduct a kind of standard hydrogeologic testing commonly done on land, known as a "cross-hole test."

"In a cross-hole test, you pump in one hole and monitor in several other holes. No one's ever done this in the seafloor. The environment is different, but in principle it's the same thing anyone would do to test an aquifer," Fisher said.

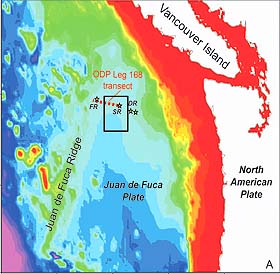

The expedition (IODP Expedition 301) will depart from Astoria, Oregon, on June 28, 2004, on the research vessel JOIDES Resolution, a well-equipped drilling platform used for years in the ODP. The scientists will be returning to an area about 120 miles (200 kilometers) west of Vancouver Island that Fisher and his collaborators previously studied eight years ago on ODP Leg 168. In a paper published last year in Nature, the researchers reported their discovery of fluid flow between a pair of seamounts in this area that are separated by more than 30 miles (52 kilometers).

"One of the big surprises from Leg 168 was that the flow rates were very high, and yet the driving forces are just a couple of pounds per square inch, not even the equivalent of one atmosphere of pressure," Fisher said. "The ocean crust is very permeable, with wide open cracks and fractures, so the driving forces are very small."

The Juan de Fuca Ridge, west of the drill site, is a place where new oceanic crust is being built as two oceanic plates spread apart and fresh lava pours out of the seafloor. To the east, the Juan de Fuca Plate dives beneath the edge of the North American Plate.

This new expedition is an opportunity to ask some basic questions about the plumbing system in the seafloor, Fisher said.

"The upper oceanic crust is the largest aquifer on Earth--it covers two-thirds of the planet. But it's a complicated system, and we don't know how well connected it is," he said. "Can you pump in one place and see a response a kilometer away? If you pump at one depth, can you see a response 500 meters below? Those are very basic questions if you want to build a model of the system. A lot of people have published papers with models of the seafloor and no data--I've done it myself. This is an opportunity to get the kind of information we need to understand the system."

New drillships equipped with different drilling technologies are being developed for the IODP, and Fisher's group plans to return to the site in a few years with one of these new vessels to conduct additional experiments.

"We'll drill another hole in between these observatories and then do some experiments where we pump into the formation and monitor the response all around it. We'll also do long-term experiments where we inject chemical tracers," he said.

All the water circulating through the ocean crust has implications on land where the oceanic plates are subducted beneath the continental plates. The explosiveness of volcanoes such as Mount St. Helens, for example, is due to water that ends up mixed with molten rock when oceanic plates are subducted deep into the Earth. Water in subduction zones may also affect the behavior of earthquake faults.

The investigation will also address questions that are of general interest to hydrogeologists who study complicated rock systems on land as well as on the seafloor, Fisher said.

The JOIDES Resolution is currently docked in Astoria, Oregon, for the first port call of the IODP. Tours for reporters and other visitors will be given on Friday, June 25. The expedition departs on June 28. For information about the media event on June 25, please contact Regina Deavers at (202) 232-3900 x1614 or rdeavers@joiscience.org.

The IODP is an international scientific research endeavor funded by the U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF), the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan, and the European Consortium for Ocean Research Drilling to conduct basic research into the history of the ocean basins and the overall nature of the crust beneath the seafloor. IODP will use new resources to support technologically advanced ocean drilling research, which will enable investigation of Earth's regions and processes that were previously inaccessible and poorly understood.

The Joint Oceanographic Institutions (JOI), a consortium of 20 academic institutions, leads U.S. participation in the IODP through the U.S. Science Support Program (see joiscience.org). Through an alliance with Texas A&M University and Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory of Columbia University, JOI leads the operations of a riserless vessel in IODP that is funded by NSF. Japan and the European Consortium for Ocean Research Drilling will also operate platforms in the program. Japan will contribute Chikyu, a $500 million riser vessel that will begin service in 2006, and Europe will operate mission-specific platforms to ice-covered and shallow-water regions.

_____

Note to reporters: You may contact Fisher at (831) 459-5598 or afisher@ucsc.edu until June 24, 2004, when he will be departing on the expedition.