Health

How early pregnancy impacts aging: implications for breast-cancer risk

New study by UC Santa Cruz team discovers that early pregnancy in mice reduces buildup of ‘confused’ cells that could lead to breast cancer later in life

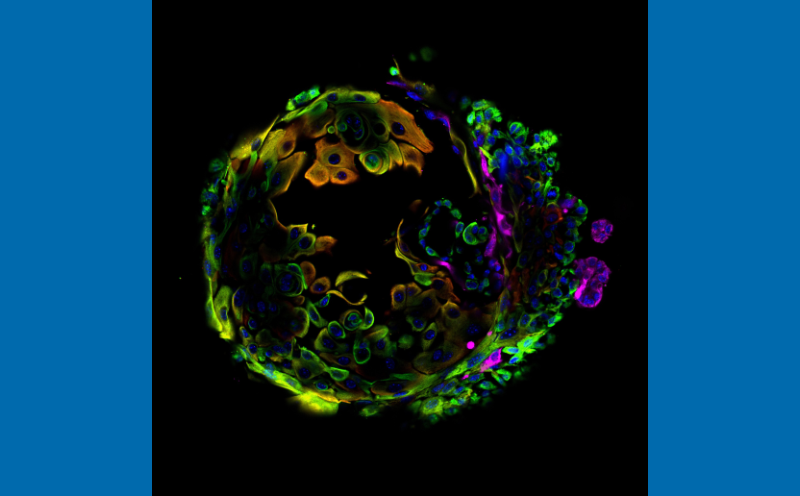

The orange cells in this image show abnormalities that emerge due to an inflammatory molecule that also accumulates with aging in mice that have not undergone pregnancy. (Credit: Sikandar Lab)

Key takeaways

- Early pregnancy may “reset” how breast tissue ages, reducing cell changes that are linked to higher breast cancer risk later in life.

- A small but potentially risky group of breast cells builds up with age in women who have never been pregnant—but is sharply reduced in those who had an early pregnancy.

- One inflammatory molecule, IL-33, appears to push breast cells toward a more cancer-prone state, offering a possible biological clue to long-term breast cancer protection.

- The findings could help explain why an early first pregnancy decreases breast cancer risk, though pregnancy-related protection takes years to emerge.

A new study by cell biologists at the University of California, Santa Cruz, suggests that an early first pregnancy may protect against breast cancer decades later by preventing age-related changes in breast cells that are linked to tumor formation. Using a mouse model designed to mimic human aging and reproductive history, researchers found that pregnancy fundamentally alters how mammary tissue ages—reducing the buildup of abnormal cells that have the ability to change their identity in a way that could seed cancer in later life.

The work, recently published in Nature Communications, addresses a long-standing puzzle in breast cancer biology. Scientists have known that while aging increases breast cancer risk, having a pregnancy early in life offers long-term protection. The cellular reason for this has remained a mystery.

In this study, researchers used single-cell technology to compare the breast tissue of old mice that had been pregnant versus those that had not. They discovered that as breast tissue ages without pregnancy, it accumulates a population of “confused” hybrid cells—cells that try to be two different types at once and display an inflammatory signal called IL-33.

IL-33 can trigger uncontrolled growth, which is a first step towards tumor formation. However, the study revealed that pregnancy acts as a “cellular reset button” that effectively blocks these confused cells from building up.

“By forcing the cells to choose a specific job and stick to it, pregnancy maintains the ‘lineage integrity’ of the tissue,” said Shaheen Sikandar, an assistant professor of molecular, cell, and developmental biology and corresponding author of the study. “This suggests that the protective power of pregnancy comes from its ability to stop these hybrid cells from accumulating in the first place—the focus of our work now.”

Modeling decades of risk in mice

A woman’s risk of developing breast cancer rises steadily with age, with most diagnoses occurring after age 50. Meanwhile, having a first child before age 30 lowers lifetime risk. To understand why, the researchers went beyond most prior studies, which focused on the short period just after pregnancy, when breast cancer risk is temporarily elevated.

Instead, they examined mammary glands at a much later stage—roughly equivalent to postmenopausal age in humans. They compared aged mice that had never been pregnant (nulliparous) with aged mice that experienced an early pregnancy. In human terms, the model corresponds to women who had their first child between about 20 and 30 years of age and were then studied after age 50.

This long view matters because roughly 75% of breast cancer diagnoses occur after age 50, according to population-level cancer statistics cited by the researchers, while most women in the United States have their first pregnancy between ages 20 and 33.

Using single-cell RNA sequencing, the team analyzed thousands of individual mammary epithelial cells to track how aging and pregnancy together reshape cell populations and gene activity.

A risky cell population builds up with age, unless pregnancy intervenes

One of the study’s most striking findings was the discovery of these hybrid cells, described that way because they express markers of both major mammary lineages—luminal and basal. The location of these cells, in the basal layer of the mammary gland, adds to their potential importance. Many studies suggest that breast tumors often arise from cells that lose their normal identity over time, particularly as women age.

To test whether the inflammatory signaling molecule IL-33 itself might drive harmful changes, the researchers treated mammary epithelial cells from young mice with IL-33. The result: The cells began to behave like those from aged, never-pregnant animals.

IL-33 exposure increased cell proliferation and promoted the formation of organoids—miniature, simplified versions of tissue—especially when combined with suppression of Trp53, a key tumor-suppressor gene. These functional changes mimic features associated with early tumor development.

“Taken together, the findings could help explain why the protective effect of pregnancy takes years to emerge, and why it persists into later life, by showing how early reproductive events can leave a lasting imprint on the aging breast,” said Andrew Olander, a graduate student in the Sikandar Lab and lead author of the study.

Pregnancy restores balance and promotes differentiation

Pregnancy did more than just reduce the number of hybrid cells. It also corrected broader age-related imbalances in mammary tissue. In aged mice that had been pregnant (parous), the usual expansion of basal cells seen with aging was normalized, and both basal and luminal cells showed a reduced ability to form organoids.

At the same time, luminal cells in aged parous mice retained molecular signatures associated with “post-pregnancy involution,” a state that may make them more visible to the immune system. The authors suggested this could enhance immune surveillance and further reduce cancer risk.

Implications for understanding breast cancer risk

Although the work was done in mice, the researchers argue that the biological principles are likely relevant to humans, given parallels in mammary gland structure and cancer epidemiology. The study does not prove that these hybrid cells directly cause cancer, but it identifies them as a plausible contributor to age-related risk—and a potential target for future prevention strategies.

“Our study lays the groundwork for understanding the complex relationship between aging and pregnancy in the mammary gland,” Sikandar said. “Future work will be focused on further understanding the role of the ‘confused’ hybrid cells in developing breast cancer.”

Other study co-authors from UC Santa Cruz include Paloma Medina, Veronica Haro Acosta, Sara Kaushik, and Matijs Dijkgraaf. They conduct research in the Department of Molecular, Cell, & Developmental Biology, and some are affiliated with the campus’s Genomics Institute, Department of Biomolecular Engineering, and the Institute for the Biology of Stem Cells. This work was funded by the Hellman Foundation, a National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute fellowship to Olander, and a grant to Sikandar.