Climate & Sustainability

New global directory of reforestation organizations helps would-be donors maximize the impact of their philanthropy

Professor Karen Holl and Postdoctoral Researcher Spencer Schubert launched the directory in partnership with nonprofit environmental media organization Mongabay

Planting trees is something most people can get behind, and tens of thousands of reforestation projects now operate worldwide. However, for donors and funders who want to support these efforts, it can be hard to identify which organizations to trust with their money and even more difficult to determine which are effective.

“I would give talks, and people would ask, ‘Who should I donate my money to?’” said Karen Holl, a reforestation expert and environmental studies professor at the University of California, Santa Cruz. “There was really no standardized way to answer that question.”

So how can a tree investor decide what organizations to support? What questions should ensure money goes toward the best outcomes for biodiversity, climate and people?

To help answer those questions, Holl and UC Santa Cruz Postdoctoral Researcher Spencer Schubert spent more than a year evaluating “intermediary organizations,” the major groups that channel funding and resources to local tree-planting projects around the world.

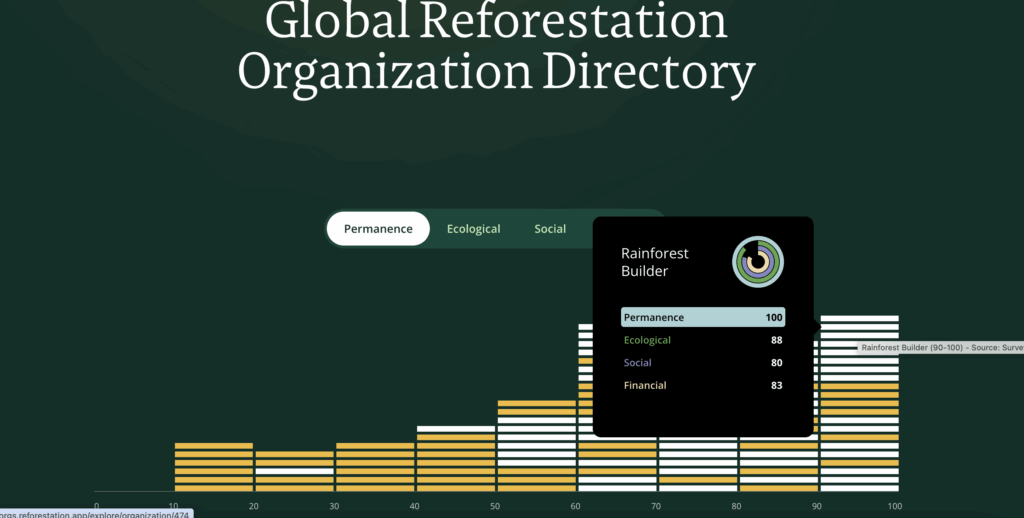

The result is a new Global Reforestation Organization Directory, developed in collaboration with Mongabay, with research funded by the Center for Coastal Climate Resilience and the MacArthur Foundation Chair at UC Santa Cruz.

The directory provides standardized information about the public commitments and transparency of more than 125 major tree-planting organizations contacted by the research team between October 2024 and June 2025. Seventy of those organizations completed detailed surveys, while researchers performed systematic reviews of websites and public reports for the rest.

How it works

The directory doesn’t rank organizations or judge individual projects — it also does not recommend projects. Instead, it shows what organizations publicly share about following scientific best practices, avoiding common mistakes and monitoring their results. The overarching goal is to provide standardized information for comparison among groups, making it easier for donors to find the ones that match their priorities.

“We’re setting the norm of what the standards are,” Holl said. “Before this, nobody had the information to compare organizations.”

Each organization in the directory received a score for its availability of information in four main categories developed based on Holl’s prior research:

- Permanence: Are the trees surviving in the long term? Do organizations have standards in place for picking effective projects, and are these projects actually addressing the causes of deforestation? This category also involves land tenure, as well as making sure organizations have strong maintenance and monitoring plans.

- Ecological: Are projects planting the right trees in the right places? This category evaluates tree species selection (Are they native? Are they useful to communities?) and seed sources to ensure genetic diversity. It also asks whether organizations are monitoring changes in biodiversity, such as an increase in wildlife.

- Social: Are local people benefiting from the project? This category assesses local community involvement throughout project phases. It looks at safeguards against displacing communities, support for landholders and monitoring of benefits to local people, including gender demographics.

- Finances: Where is the money going? This category examines transparency around funding sources, disclosure of how much money goes to tree-planting organizations versus administrative costs, and whether there is long-term maintenance funding.

Organizations can be sorted by category and score, or viewed individually, showing their data across all categories. The results are a useful starting place for comparison, but the researchers caution against discounting organizations based solely on the scored criteria. Not all organizations work the same way. Some work in remote areas where certain social criteria don’t apply, while others tailor standards to local conditions rather than impose rigid requirements. These flexible approaches can sometimes be more effective than one-size-fits-all policies.

The absence of information on an organization’s website also doesn’t necessarily mean the organization has neglected those criteria. Some excellent programs may lack the staff or resources to maintain public dashboards. However, public transparency signals that an organization understands the complexities involved in reforestation and has the capacity to organize, monitor and report results.

Promoting transparency

As an investor or philanthropist, picking the right organization matters. Not all tree-planting efforts pack the same punch. And while increasing tree cover has many potential benefits, it can also have negative consequences, such as destroying diverse grasslands, introducing invasive species and displacing deforestation into remnant forests. Projects also have the potential to benefit or harm the communities they involve.

Holl’s prior research has shown that many organizations claim to follow best practices but don’t share enough details about their actual results.

To organizations, Holl’s message is direct. “What are your goals? And if those are your goals, what are measurable objectives and how are you measuring them? You need to be clear about what you’re trying to achieve and honest about how well projects are meeting their targets.”

Organizations claiming to restore biodiversity should measure biodiversity, she said. Those focused on community livelihoods should track whether locals are benefitting from the projects. By evaluating these organizations, “our goal was not to be punitive,” Holl said, “but to try to incentivize groups to follow best practices.”

Holl sees evidence that change is already underway. Organizations are improving their monitoring commitments compared with earlier research. But “actually monitoring and also making those data public,” she said, “those are the next steps.” Many organizations are collecting data, “but then there isn’t a follow-through on the public reporting side,” Schubert added. “There’s a disconnect.”

For now, the directory offers something previously unavailable: a systematic way to compare how major reforestation organizations approach the complex challenge of growing trees that survive, benefit communities and support biodiversity for the long term. Current funding for the project only supports directory updates through December 2025. The team is seeking additional resources to maintain the platform in the long term as organizations update their practices and new tree planters enter the field.

This story was adapted from original reporting by Mongabay