Earth & Space

New study on avian malaria finds most of Hawaii’s birds contribute to deadly pathogen’s transmission

Research led by UC Santa Cruz finds that both non-native and native birds play a key role in the transmission of a disease that has contributed to the extinction of over a dozen species of Hawaii’s native birds

A Hawai'i 'Amakihi, one of just 15 surviving bird species in the Hawaiian honeycreeper family, is a frequent reservoir for avian malaria. Originally, more than 50 distinct species of Hawaiian honeycreeper existed. Some populations of ‘Amakihi are resistant and can survive infection.

Credit: Christa Seidl

Press Contact

Key takeaways

- The study found that both native and introduced birds can pass the parasite to mosquitoes, meaning nearly any bird community can help keep the disease circulating wherever mosquitoes survive.

- Birds with very low levels of the parasite can still spread avian malaria, countering the idea that only heavily infected birds drive transmission.

- Some birds play an outsized role in spreading avian malaria. This study found that mosquitoes feed more often on certain birds—including the introduced House Finch and native ‘Amakihi—making these species key drivers of disease transmission across Hawaii.

New research on avian malaria, which has decimated Hawaii’s beloved birds, explains how non-native birds play a key role in transmission and contribute to the widespread distribution of the disease. This disease threatens many native species that are integral to Hawaii’s identity and its unique and fragile ecosystems.

Avian malaria, caused by a microscopic parasite and transmitted by mosquitoes, has contributed to the extinction of more than a dozen species of Hawaii’s native birds—and is currently threatening those that remain. The disease infects birds’ red blood cells, leading to low blood oxygen levels and damage to the liver and spleen. And over the past four decades, the vivid colors and songs of these tropical birds have been disappearing due to habitat loss, introduced predators, and diseases such as avian malaria and avian pox.

This new study, from the lab of ecology and evolutionary biology professor A. Marm Kilpatrick, helps answer the mystery of which species of birds are sustaining the spread of malaria in Hawaii. Previous research pointed to native birds, due to the high levels of malaria in their blood following infection. But many habitats in Hawaii have no native birds and yet still have substantial malaria transmission.

Reservoir birds

The team found that most species of birds—both native and introduced—were partly infectious and could transmit avian malaria to biting mosquitoes. This suggests that all communities of birds in Hawaii could support transmission of avian malaria wherever temperatures are warm enough for mosquitoes and the development of the deadly pathogen they carry.

“What surprised us most was how effectively avian malaria was transmitted to mosquitoes, even from birds carrying vanishingly small parasite loads,” said Christa Seidl, who led this work as part of her Ph.D. studies at UC Santa Cruz.

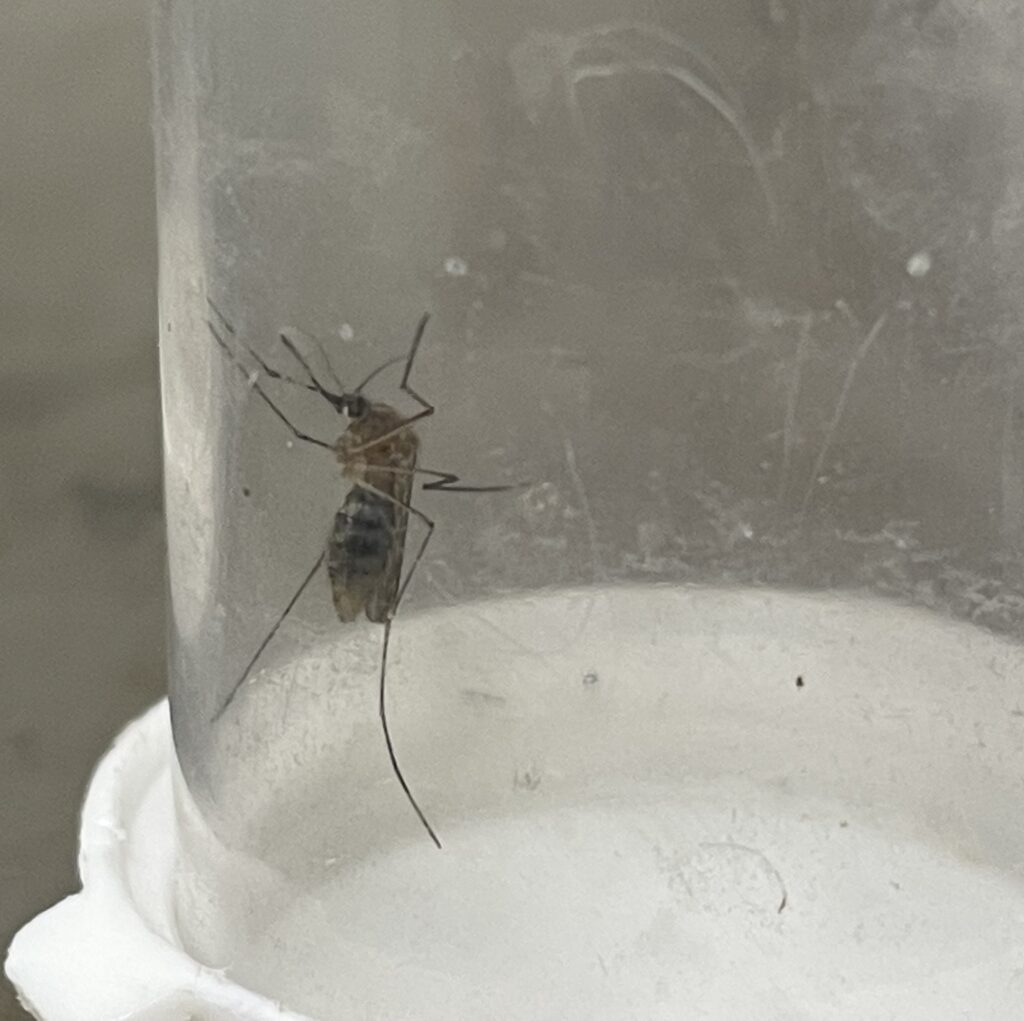

For this study, the team performed a series of laboratory experiments where they determined the fraction of mosquitos that became infected after feeding on birds with different levels of malaria. They combined these data with 1,275 measurements of the levels of malaria in 17 different species of birds, including seven native species and 10 introduced species.

Surprisingly, the integration of these two datasets showed that species broadly overlapped in their infectiousness for avian malaria. This was due to a relatively gradual relationship between malaria levels and infectiousness, and enormous variation within species in malaria levels. This suggested that, counter to previous beliefs, the differences between native birds and introduced species in infectiousness were relatively small.

“The similarity in infectiousness among species helped explain the widespread distribution of malaria we found among sites with very different bird communities,” Seidl said. “We found malaria at 63 of the 64 sites we sampled.”

No escape

Next, the team used relative patterns of malaria infection across sites to estimate mosquito feeding patterns on different bird species. They integrated these estimates with the infectiousness of each species and their relative abundance at 11 focal sites to determine the role of different species in transmission and overall community infectiousness. They found that bird communities across all 11 sites were similarly infectious—due to the similarity in infectiousness among species—but some bird species played disproportionate roles in transmission.

“The patterns of infection suggested that some species were fed on much more frequently than others by mosquitoes, and these species played a key role in transmission,” Kilpatrick said. The most important species across many sites was the introduced House Finch, whereas a native species, Hawai’i ‘Amakihi, was the next most important species wherever it was present. Many other species made smaller contributions to infecting mosquitoes because they were less frequently fed on by mosquitoes, but nearly all were infectious enough to sustain avian malaria transmission.

“These results show that avian malaria in Hawaii is an extreme generalist and can replicate to sufficient levels to support transmission in most species,” Kilpatrick said. “As a result, few, if any, warm low-elevation habitats where mosquitoes are present will be free from this pathogen, which will continue to threaten Hawaiian birds with extinction.”

This work helps inform local conservation efforts in Hawaii, which include mosquito control, captive breeding, and habitat restoration, especially at high mosquito-free elevations.