Earth & Space

‘Super-Jupiter’ exoplanet has markedly different atmosphere than our gas giant, new study finds

Analysis of early direct images from James Webb telescope show immense dust clouds on brown dwarf that lead to a blurring of atmospheric lines—and scientific consensus

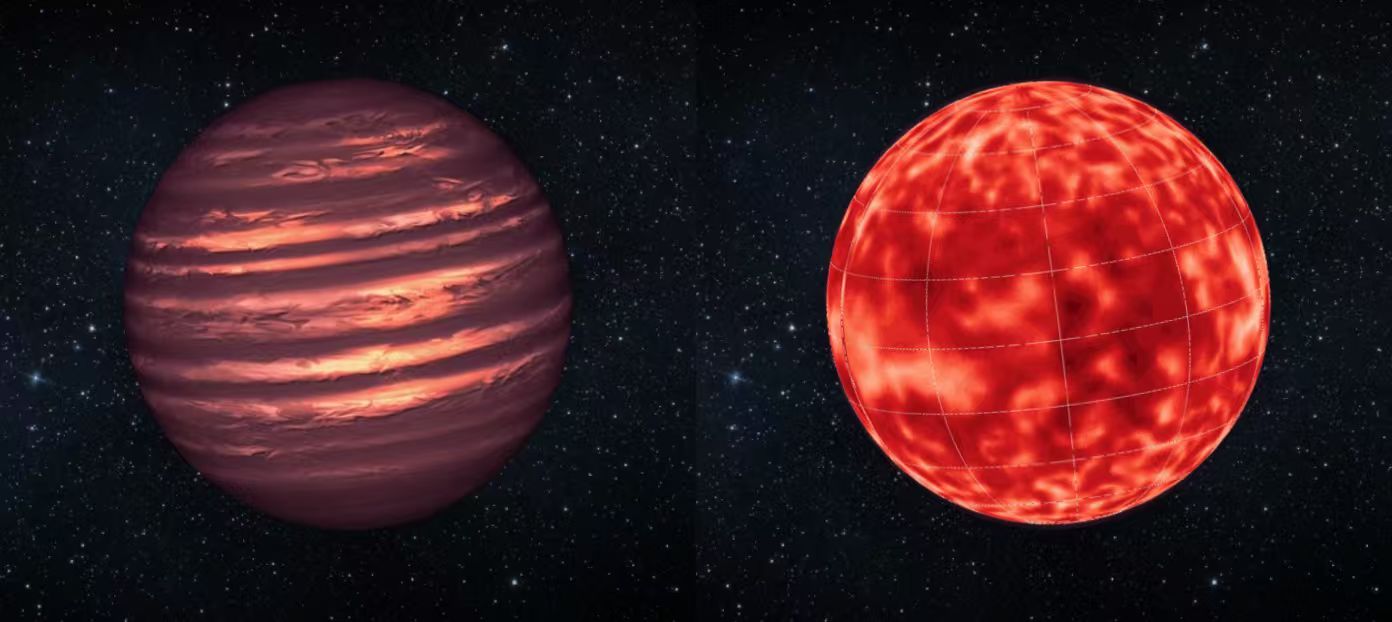

Left: Artistic conception of the longheld astronomical assumption of brown dwarfs resembling Jupiter in appearance, displaying prominent multiple zonal bands and stable vortices similar to the Great Red Spot. (Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech) Right: Study team’s modeled general circulation for super-Jupiter VHS 1256B.

Press Contact

Key takeaways

- James Webb Space Telescope observations reveal that the atmosphere of a brown dwarf classified as a “super-Jupiter” is far more chaotic than that of our own gas giant—challenging popular assumptions.

- This study focused on the exoplanet VHS 1256b, in the constellation Corvus some 40 light-years from Earth.

- Through direct imaging and advanced simulations, researchers concluded that VHS 1256b likely lacks Jupiter’s neat zonal bands and stable vortices due to this type of exoplanet’s much hotter temperatures and unique wave dynamics.

In the first high-profile paper of a program to observe planets beyond our solar system with the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), a team of scientists including Professor Xi Zhang at the University of California, Santa Cruz, have used direct imaging of a mysterious exoplanet to dispel a long-held assumption about the atmospheres of celestial objects of its size.

The exoplanet in question is known as VHS 1256b, in the constellation Corvus some 40 light-years from Earth. It is classified as a brown dwarf, which are enormous orbs sometimes called “super-Jupiters” when their mass hovers around that of the gas giant in our home system. As such, astronomers believed these kinds of exoplanets had atmospheres that swirled and variably shined in a similar fashion as Jupiter’s.

NASA selected VHS 1256b for close observation by the JWST Direct Imaging Early Release Science Program because its brightness in the infrared spectrum showed the largest variability detected on any exoplanet to date. The new findings seem to answer why VHS 1256b has been winking at astronomers so wildly.

With the use of computer modeling to simulate the atmospheric dynamics of VHS 1256b, then comparing the model with observational data from the JWST direct-imaging program, the co-authors of this new study concluded that the exoplanet’s atmosphere differed significantly from the series of horizontal “zonal bands” and stable vortices like Jupiter’s Great Red Spot.

“The mechanism of giant planets’ atmospheric circulation has long been an important and unresolved question in planetary science,” said co-author Zhang, a professor of Earth and planetary sciences at UC Santa Cruz. “These novel wave dynamical processes on super-Jupiters provide us with a unique perspective to examine our fundamental understanding of this problem.”

Full-spectrum observations by the JWST direct-imaging team, which includes UC Santa Cruz astronomy and astrophysics professors Andy Skemer, Steph Sallum, and Jonathan Fortney, found that immense dust clouds loom at low altitudes of VHS 1256b. Then, based on their analysis, Zhang and his co-authors determined that those clouds radiate heat that results in large-scale equatorial waves that organize giant dust storms, creating a more chaotic atmosphere compared to the neatly striped Jupiter.

NASA launched the early-release program in 2022 to develop the techniques and technology for direct, high-contrast imaging of exoplanets, especially those with traits of a habitable atmosphere like Earth’s. NASA’s other early-release science team for JWST exoplanet characterization, the transiting planet program, is led by Professor Natalie Batalha, head of UC Santa Cruz’s astrobiology initiative.

The reason why the atmospheric circulation of VHS 1256b, and perhaps other exoplanets in its class, is so distinct from Jupiter’s derives from the nature of brown dwarfs and their much hotter temperatures than Jupiter. Brown dwarfs are unable to sustain hydrogen fusion in their cores and cool down over billions of years—hence, their lackluster nickname. They are often used as proxies to study giant planets.

Most brown dwarfs exhibit some variation in self-luminosity, which is caused by their patchy surfaces and their rotation that leads to small periodic fluctuations. But some brown dwarfs, like VHS 1256b, show significant irregular variations in observable brightness—making them ideal laboratories for studying the atmospheric circulation of extrasolar giant planets.

Zhang co-wrote the paper with lead author Xianyu Tan, a fellow at Shanghai Jiao Tong University’s Tsung-Dao Lee Institute. They initiated the research project and developed the core concept, and Zhang helped Tan set up and run the numerical simulations, contributed solar system expertise for comparative analysis, and shaped the overall narrative. Skemer supervised and contributed to the JWST data analysis.

The new study, published on November 26 in the journal Science Advances, is titled “Large-amplitude Variability Driven by Giant Dust Storms on a Planetary-mass Companion.”