Earth & Space

UC Santa Cruz joins NASA project probing ocean worlds for signs of life

Earth and planetary sciences professor Andrew Fisher will lead hydrogeology simulations to study how water, heat, and chemicals circulate between rocky seafloors and subsurface oceans on worlds like Europa and Enceladus

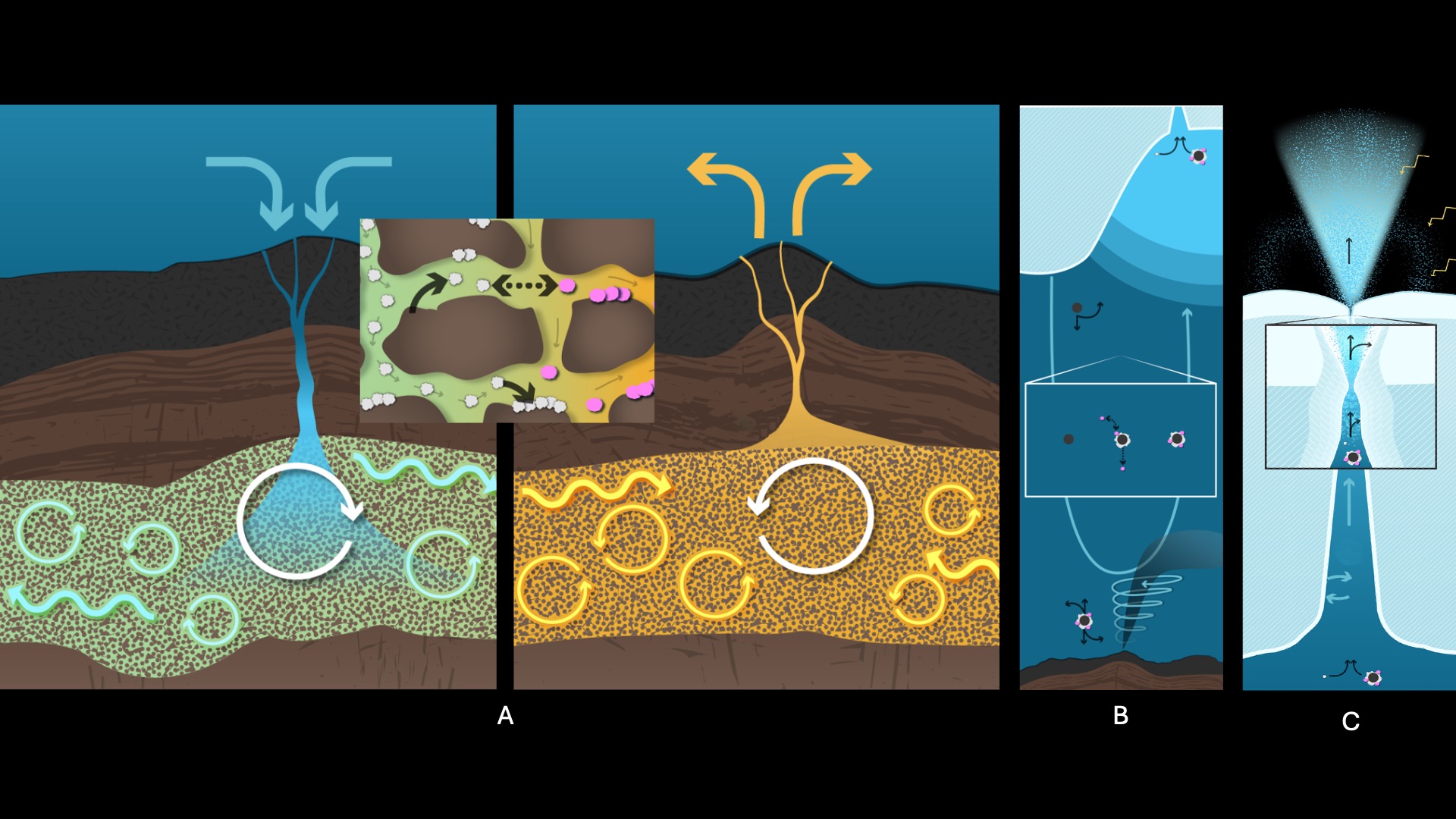

The Investigating Ocean Worlds (InvOW) project will measure organic compounds across three domains: the subseafloor (A), the ocean (B), and the cryosphere (C), with a goal of helping NASA apply what has been learned about the Earth’s oceans to other places in the solar system. (Credit: Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

Key takeaways

- The project aims to strengthen future life-detection missions by improving how scientists interpret organic carbon signals, which can be altered as they move through an ocean world’s seafloor, ocean, and icy shell before reaching spacecraft instruments.

- Recent UC Santa Cruz modeling studies suggest hydrothermal vents may be common on icy ocean worlds, a finding that significantly increases the likelihood that these distant environments could support life.

- The project brings together 16 laboratories and multiple disciplines to study ocean worlds as integrated Earth-like systems, combining modeling, lab experiments, and fieldwork to better understand how geological, chemical, and possible biological processes interact.

Ocean worlds such as Jupiter’s icy moon Europa and Saturn’s counterpart, Enceladus, could be among the most favorable places to discover life beyond Earth—and perhaps even a second, independent origin of life.

With NASA’s Europa Clipper spacecraft scheduled to arrive at Europa in 2030 to determine whether its icy crust or under-ice ocean might be able to support life, the space agency has given the green light to a project to investigate ocean worlds in new, collaborative ways. The Investigating Ocean Worlds (InvOW) project team spans 16 laboratories across the United States, including the lab of Earth and planetary scientist Andrew Fisher at the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Fisher is one of the project’s 17 co-principal investigators, and he and students in the Earth and Planetary Sciences Department will explore hydrogeology by simulating how water may move in and out of the rocky seafloors of selected ocean worlds. “We are trying to understand how water might carry heat and dissolved chemicals from the interior into the ocean, and how these flows might be detected during future missions,” Fisher said.

The five-year InvOW project will be led by the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) and is slated to begin in 2026. In particular, InvOW will aim to improve the analysis of data related to carbon-rich molecules that could be an indicator of biological activity and that will be a focus of future life-detection missions.

According to Chris German, WHOI senior scientist and InvOW principal investigator, the new project will investigate how physical, chemical, and possibly biological processes active on ocean worlds like Europa or Enceladus might affect data collected by future space missions that hunt for signs of life.

“If you are alive today, this is the first generation where the question of whether there is life elsewhere in the universe could be answered in your lifetime,” said German. “Previously, this was an abstract, intellectual, and philosophical question. We now know enough to say that it is entirely plausible that there is life out there, within humanity’s reach, and we just need to go and look.”

The InvOW project team will integrate a combination of disciplines—ocean, polar, and space sciences—and use interdisciplinary approaches such as theoretical modelling, laboratory experiments, and fieldwork to investigate three different domains on ocean worlds: the rocky subseafloor, the ocean itself, and the icy outer shell, known as the cryosphere.

A unifying focus will be to investigate how organic materials—potentially indicative of life—might be modified as they travel through Europa’s or any ocean world’s different domains before they reach a spacecraft’s detection system.

“Identifying carbon compounds on ocean worlds that would provide unambiguous evidence for the presence of life is challenging,” explained German. On Earth, ocean life consumes so much of the organic carbon present, very little is left unconsumed. As a result, there is little to no “signal-to-noise” problem between detecting organic compounds that are the result of life against a background of non-biological material.

In space, the opposite may be true. On other ocean worlds more distant from the Sun, where there is significantly less energy to support biological activity, non-biological organic matter might dominate.

“With focused research, there’s a lot that can be done—a tremendous amount of groundwork that can be laid— to optimize the design and scientific yield of future missions,” said InvOW deputy principal investigator Tori Hoehler, director of the Center for Life Detection at NASA’s Ames Research Center. “The InvOW award gives us the opportunity to do just that, by bringing together planetary scientists and Earth oceanographers to understand alien oceans the way we understand our own—as complex systems where geology, physics, chemistry, and possibly biology, work together in concert.”

A study published last year and led by Fisher used complex computer modeling to show that hydrothermal vents like those found on our own ocean floors could also exist on two ocean worlds. A follow-up study led by UC Santa Cruz graduate student Ryu Akiba, published in September, extended those results to a wider range of potential ocean-world conditions—raising the odds that life could exist on these distant bodies as well.

To learn more, read the lead WHOI announcement.