Arts & Culture

Ahead of new game release, Animal Crossing: New Horizons book reflects on comfort, community, and capitalism

Professor of Computational Media Noah Wardrip-Fruin speaks on themes explored in his new book

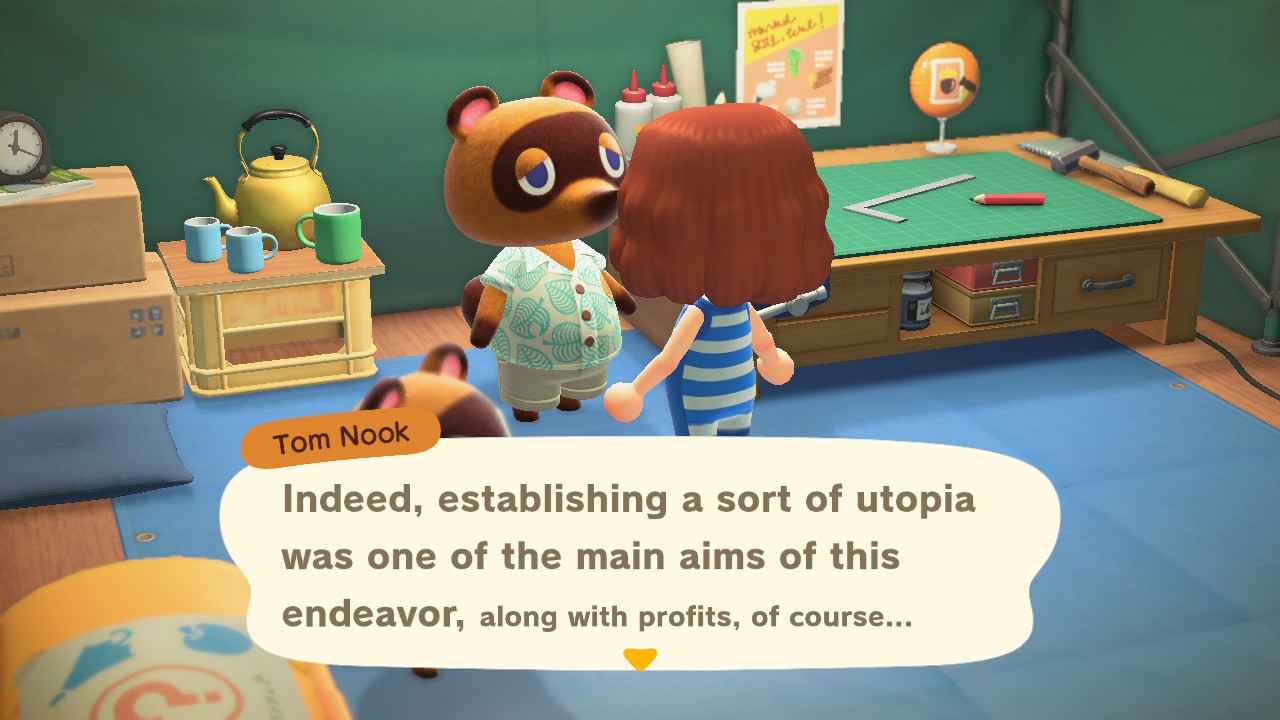

A screenshot from Animal Crossing: New Horizons shows the character Tom Nook revealing deeper themes of the game.

Press Contact

Remember Animal Crossing: New Horizons? During the height of its popularity during the COVID-19 pandemic, the game, built for the Nintendo Switch console, was averaging 1 million copies sold per day. Now, almost six years since the start of the pandemic, University of California, Santa Cruz Professor of Computational Media Noah Wardrip-Fruin published a book titled “Animal Crossing: New Horizons, Can a Game Take Care of Us?”

The book is part of a new collection published by University of Chicago Press called ‘Replay,’ a series of short general-interest books about a single game. It’s an exploration of how and why the game resonated so deeply with people during the pandemic, reflecting on themes of comfort, ability/disability, “safe capitalism,” and more. Ahead of Nintendo’s planned January 2026 release of a new version of the game, we sat down with longtime games expert Wardrip-Fruin to learn more about lessons drawn from New Horizons.

The following Q&A has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Q: Why Animal Crossing: New Horizons? What about this game intrigues you enough to write a full book on it?

A: Part of it is personal experience, I spent hundreds of hours playing Animal Crossing: New Horizons with my kids during the first year of the pandemic. And part of it is cultural — the game had a huge impact. It might be a little hard to remember now, but Biden had an island in Animal Crossing, the Detroit Lions announced their season through Animal Crossing, the Monterey Bay Aquarium did livestreams in Animal Crossing. It seemed to really hit people in a way that this series never had before, and I was interested in why that was.

Q: Why do you think the game struck a chord with so many people during the pandemic?

A: Most games don’t provide safety, what they provide is risk, danger, excitement. But Animal Crossing really offers safety—and offers it in return for doing what the game tells you to do. If you do the game tasks, you basically can’t fail. On the other hand, you can’t do anything but the tasks. I think that safety was very important, but it was also limiting in ways that weren’t always obvious. All the most interesting characters in the game have businesses, and so my kids were inspired to try to start their own businesses. But the game didn’t recognize anything they were doing. Basically all you can do is the piecework that’s assigned to you—reflective of the gig work that was so common during the pandemic.

I think the other thing that led to it being so big was that, especially once you’d progressed through the main game, it became a place to hang out, a place for community with other players. That community was really hard for people to get.

Q: Are there any particular memories from your time playing the game during the pandemic that stand out or influenced the book?

A: When I realized I was going to write a book about the game, I actually got a second Switch, so I could use it as my research device, and the family Switch could stay the family Switch. When I did that, whole new areas of the game opened up, because when two players have their own Switches, they can do much richer multiplayer modes than when sharing.

I’m disabled, and I was able to do things like play tag, hide and seek, and other games like that that my son had never been able to play with me because I’m just not able enough. It was really rewarding for him and for me. Animal Crossing is interesting in that it makes possible types of activity that are just…hanging out.

One of the themes of the book definitely is my own position as someone with limitations from my own body, and everybody having limitations from the pandemic. The place of Animal Crossing in my life and in the general culture, I think, had a lot to do with those limitations.

Q: How do you see connections and communities emerge in the game?

A: With the online version of the game, players can go and visit other people’s islands. I started reading more about how other people used the feature of visiting strangers’ islands, or visiting people they knew from real life’s islands—and some of it was kind of depressing.

There’s a commodity speculation built into the game—it’s called the “stalk market,” but it’s for turnips. The way the stalk market works is, you buy turnips, which go bad after a week, there’s a new price morning and evening, and you’re supposed to check the price until you find what you think is the best price you’re going to get, and sell your turnips before they go bad. But you can do this at other people’s islands, too. So people created these groups of hundreds of people who would share their turnip prices, and it became this reproduction of Wall Street, where if you have lots of insider information, you can make lots of money. But for the ordinary person, it’s kind of a loser’s game.

On the other hand, people in the disabled community, people in queer communities, people in lots of communities that were being targeted during this period really were able to use Animal Crossing as a space for supportive community—and also for things like protests. There were Black Lives Matter protests in the game, there were Free Hong Kong protests in the game.

Any sort of virtual protest is a way of showing solidarity and concern around an event or a group of people, and that way, it’s a lot like an in-person protest. On the other hand, the sense of community is different, I think you can only have eight people on an island at a time. So you’d have these distributed small protests, instead of being in a huge group. The BBC reported that Animal Crossing was removed from sale in China amid Hong Kong protests, so clearly somebody thought it had an impact outside of the game!

I came to have really mixed feelings about Animal Crossing by the end, where I could see how powerful the community it offered was for people, but at the same time, it really felt like it embedded a bunch of neoliberal ideas that I wasn’t sure I wanted to have kids all over the world exposed to.

Q: You spend time exploring the concept of “safe capitalism.” What is this and what insights should we take away?

A: In most economic games where there’s a lot of gathering resources and buying and selling like there is in Animal Crossing. These games involve economic risk—you can go bankrupt. But in Animal Crossing, you can’t. You can run out of money because you bought too much stuff, but that doesn’t really prevent you from doing anything.

My thought about the assigned role that you play in the economy of Animal Crossing, where basically you do nothing but gig work, is that maybe that isn’t the ideal vision of the economy that we want to give to kids. It’s comforting and all that, but it’s a very passive role. You can never really aspire to have any project of your own. My kids wanted to take initiative, but discovered there was no mechanism.

Q: What is video game manipulation and how is it relevant to this game?

A: Video games definitely use forms of psychological/ behavioral economic manipulation.

We talk about it most in terms of mobile games, [which incentivize in-app purchases], but Animal Crossing uses a bunch of these same techniques. For example, if you log in every day and go to this ATM-like thing called the Nook Stop, you get increasing amounts of currency as a bonus. If you ever skip a day, you get knocked back down to the minimum again. This creates a really powerful loss aversion that I especially saw in my kids. It didn’t matter what the family plan for the day was, we had to log into Animal Crossing at least once.

There’s also things that are maybe less manipulative, but still create powerful motivations that are maybe more than parents want their kids to experience.

Again, I think the pandemic made people feel a bit differently about that than they might otherwise. There was so much feeling that routine and structure had been wiped away, that saying, ‘Oh, I’m gonna log into Animal Crossing every morning,’ felt like ‘I’m getting a piece of my routine back.’ It’ll be really interesting to me to see what happens when the next Animal Crossing comes out—which presumably won’t be during a global pandemic—and see how people respond to these things that are both manipulative, but also structure and progress creating.