Technology

UC Santa Cruz scientists to develop diamond-based sensors to monitor fusion-energy generation

Diamonds can withstand the extreme radiation inside the reactor of a nuclear power plant

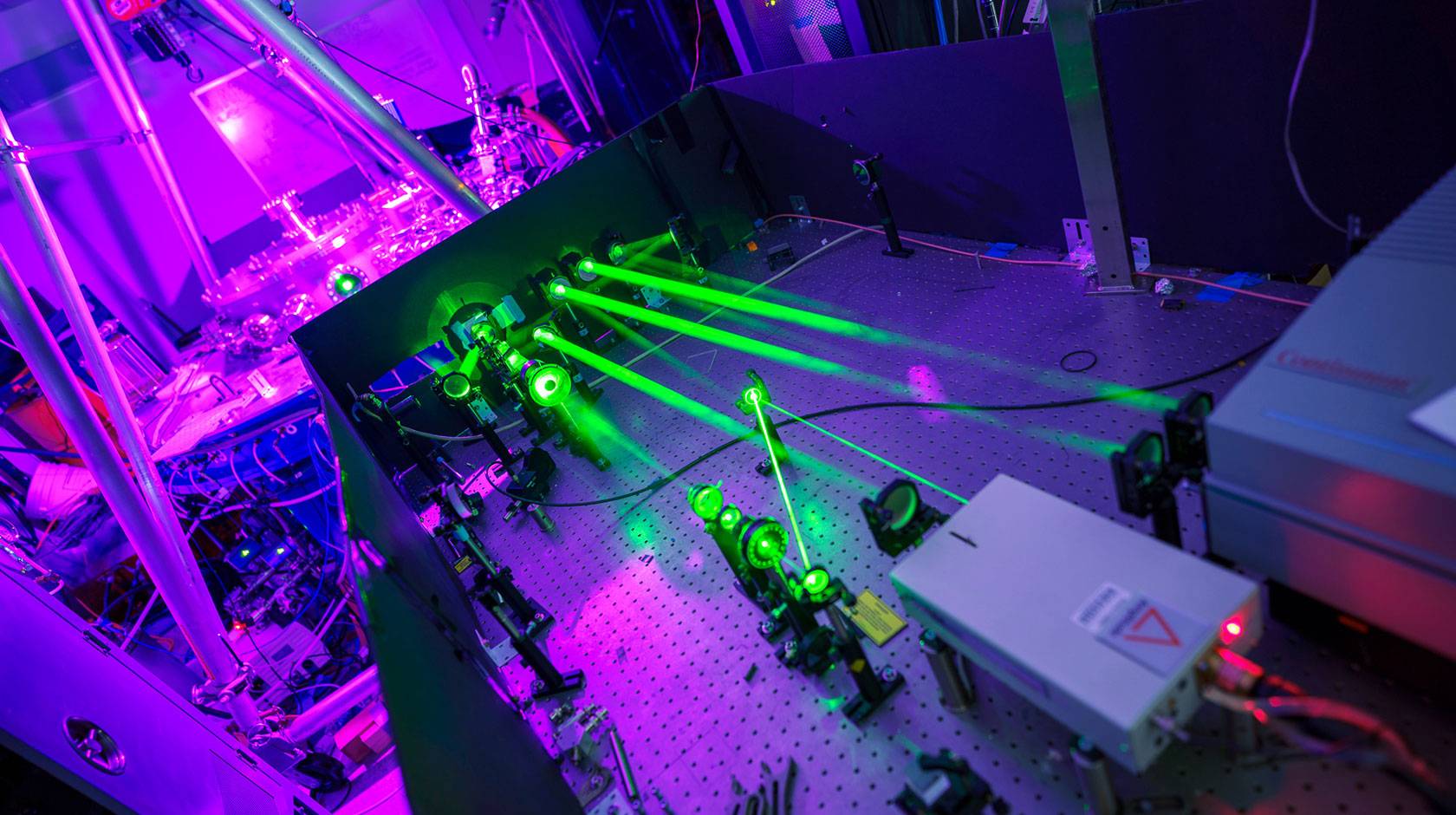

Experiments in the lab of UC San Diego Professor Farhat Beg, the lead researcher on a project that will investigate materials under extreme fusion conditions, in collaboration with physicists at UC Santa Cruz. (Credit: David Baillot / UC San Diego)

Press Contact

Key takeaways

- Researchers at the Santa Cruz Institute for Particle Physics are developing diamond-based sensors to monitor fusion reactions, a critical capability for safely operating future nuclear power plants.

- UC Santa Cruz will receive $555,000 of an $8 million multi-campus fusion-energy initiative to fuel the state’s global leadership in nuclear fusion.

- This work is part of a broader, rapidly accelerating fusion ecosystem in California, where major scientific milestones, significant private investment, and government mandates are driving efforts toward building the first commercial fusion pilot plants.

In the quest to meet the state’s growing demand for clean electricity, the University of California has awarded multiple UC campuses with research grants totaling $8 million over three years to fuel California’s global leadership in nuclear fusion.

Physicists at UC Santa Cruz will receive $555,000 of that to develop a literal gem of a monitoring system that such power plants will need to safely generate fusion energy—a system that incorporates artificial diamonds to detect the nuclear “burn” products of fusion reactions.

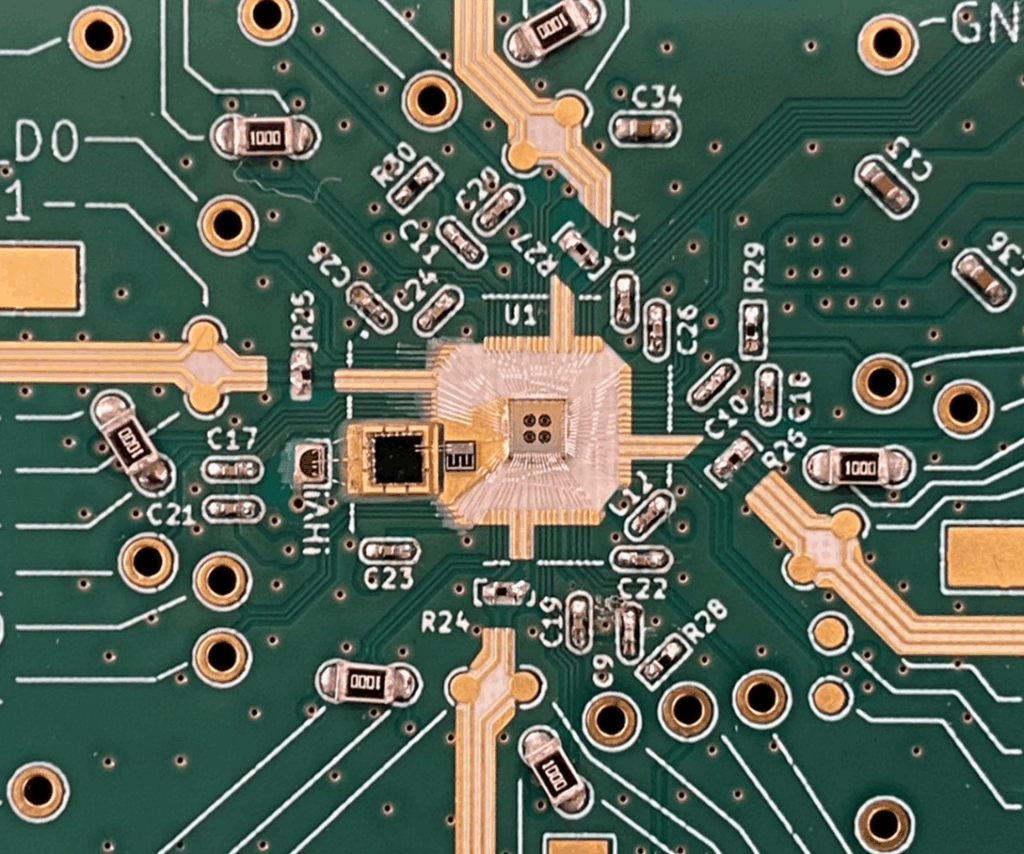

Diamonds are widely known for how well they can withstand radiation, which would reach extreme levels inside a nuclear reactor that produces fusion energy at commercial scale. Researchers at the Santa Cruz Institute for Particle Physics (SCIPP) have been at the forefront of the particle physics community’s international effort to develop silicon sensors for use in colliders and other fields.

But these sensors—known as low-gain avalanche diodes (LGADs)—can’t withstand extreme-radiation environments. Aside from fusion-energy production, this also rules out their use in important fields such as space science. So SCIPP has partnered with the small business Advent Diamond, which can make the sensor substrate with diamonds instead of silicon.

The Science Division provided SCIPP faculty member Bruce Schumm with just over $48,000 in seed funding for this project, based on its alignment with the division’s core emphasis on research impact. That seed money was vital because, so far, no government agency has been willing to fund a collaboration between SCIPP and Advent, according to Schumm.

In other words, the seed funding had the synergistic effect of strengthening SCIPP’s proposal to contribute to the UC fusion-energy initiative. “Advent is one of the few companies in the world that can do the sort of boutique R&D needed to develop diamond sensors as nuclear particle detectors,” said Schumm, the Long Family Professor of Experimental Physics. “Dean Bryan Gaensler’s willingness to seed this work has at last enabled a collaboration that we have sought to get off the ground for several years now—in a direction that inspired a significant part of our thinking about diagnostics for commercial fusion power plants.”

Growing interest and investment

Fusion is a type of nuclear reaction that powers our sun. It emits no greenhouse gases, generates very little waste, and is fueled by hydrogen—the most abundant element in the universe. Given fusion’s potential to address energy and national security challenges, the federal government has long underwritten the complex pursuit of harnessing this incredibly powerful reaction for the generation of essentially unlimited electrical power.

In 2022, scientists at the UC-managed Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory crossed a critical fusion-ignition barrier in a lab for the first time, sparking a nuclear reaction that emitted more energy than it consumed. Since that initial blast, the team at Livermore Lab has since achieved fusion ignition multiple times, with ever-increasing energy output.

Significant interest in fusion energy has built up in recent years due to these breakthrough experiments demonstrating ignition, burning plasma, and energy gain for the first time in the laboratory. Meanwhile, over $10 billion in private investments have been made into a nascent thermonuclear-fusion industry.

In addition, the U.S. Energy Department recently started investing in the development of fusion-energy hubs. Along with that, state Senate Bill 25 “supports the development of the fusion energy ecosystem in California, including the workforce and supply chain necessary to advance fusion research, development, demonstration, and deployment.” The bill aims to have a fusion pilot plant in California by 2030.

In that context, the UC Initiative for Fusion Energy provided two grants of $4 million over three years. The two winning teams are composed of UC faculty across a wide range of disciplines, representing five UC campuses and the Lawrence Livermore and Los Alamos National Laboratories. The funds derived from fee income the university receives for managing the two labs.

Fusing forces

Despite all the momentum, however, significant challenges remain before fusion can be safely and economically harnessed in power plants. UC Santa Cruz’s scientists join a team of fusion-energy experts from UC San Diego, Los Angeles, Irvine, and the two national labs. Collectively, they will investigate materials under extreme fusion conditions, diagnostics that can measure the profile of individual fusion burns in an environment of extreme radiation, and issues related to regulatory policy and public perception.

The team, led by UC San Diego Professor Farhat Beg, will include students and leverage advanced manufacturing, measuring, and computational tools to model and develop new materials, or variants of them. Their focus will be on “three Ms”—model, manufacture, and measure. Simone Mazza, an assistant research scientist at SCIPP, will lead UC Santa Cruz’s charge to develop an “extreme radiation-hardenend” detection system for plasma monitoring.

“Despite significant progress, important questions pertinent to engineering and design challenges remain before fusion energy can successfully transition from the laboratory to a commercially viable power plant,” Mazza said. “To address these challenges, a coordinated effort is warranted between academia, national laboratories, and industry.”

Accelerating progress toward a future powered by abundant, stable, zero-carbon fusion energy is a key priority for U.S. Secretary of Energy Chris Wright. In his first secretarial order, Wright identified nuclear fusion as a technological breakthrough that will unleash American energy innovation, meet the nation’s rising energy demands and maintain its global security and competitiveness.

Fusion energy likewise offers tremendous potential to help California meet its ambitious goal of generating 100 percent clean energy by 2045 and advancing the state as the epicenter of global innovation. In an October 2025 gathering at UC Berkeley, Governor Gavin Newsom signed a bill dedicating $5 million in state funds to research and development supporting the commercialization of fusion energy, with the goal of delivering the world’s first fusion energy pilot project in the state by the 2040s.

For more information, read the full announcement in the UC Newsroom.