Earth & Space

Star light, world bright

Exploring remote planets with extreme light-bending inventions

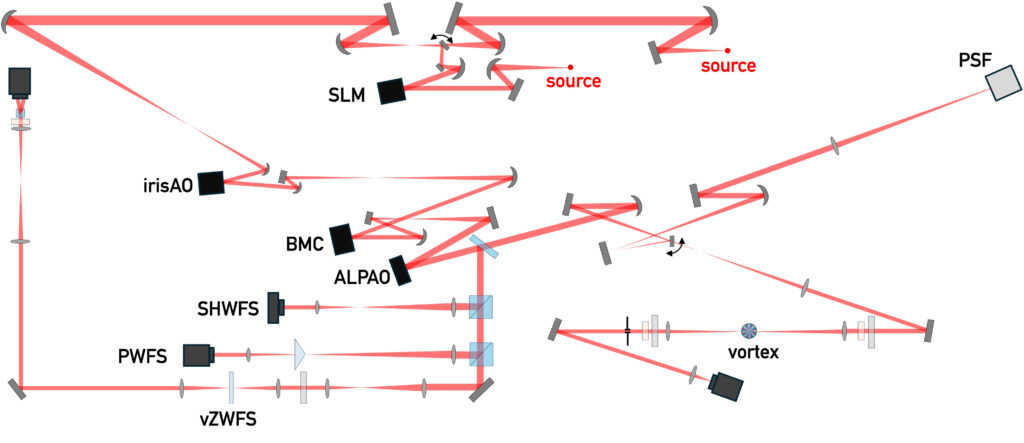

An overhead view of the upgraded SEAL facility (Photo by Daren Dillon).

Of all the circumstances a planet could form, Earth followed just the right recipe for life to proliferate. Were the conditions different, our home could have been a barren rocky world like Mars, or a gaseous giant like Jupiter. Many more planets of various kinds lie beyond our solar system, and the ingredients that make each of them unique are what drives a burgeoning subfield of astronomy known as exoplanet science.

Scientists today recognize that most stars in the universe host exoplanets, and with almost 6,000 already found since their first detection in the 1990s, billions more are waiting to be discovered.

Researchers at UC Santa Cruz’s Santa Cruz Extreme AO Lab (SEAL) are aiding the discovery effort through the development and testing of highly specialized instruments that are crucial for optimum performance of Earth-bound telescopes, allowing astronomers to get a crystal clear look at the sky.

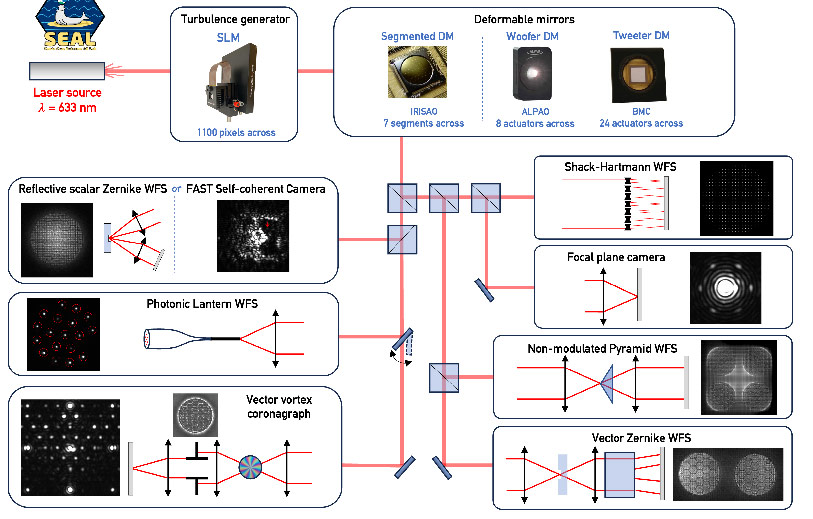

Observing stellar systems on the ground is challenging, however, due to the way our planet’s atmosphere distorts light traveling through it. The SEAL facility consists of a unique adjustable testbed for developing new technology to enable scientists to see smaller, more Earth-like exoplanets.

“Taking images with a telescope on Earth without the appropriate equipment is like standing at the bottom of a swimming pool trying to look up through the water,” said Rebecca Jensen-Clem, SEAL’s principal investigator and director of UCSC’s Center for Adaptive Optics (CfAO). “Without adjustments, we’re not going to get a very good image.”

Much like the murky waters of the deep ocean, the unpredictable fluidity of Earth’s atmosphere can distort any light that penetrates it. While space telescopes can avoid this issue as they travel far above Earth, ground-based telescopes are not so lucky.

That is exactly the problem SEAL is designed to address. The goal of the lab is to create adaptive optics machinery for directly imaging exoplanets via ground-based telescopes.

To accomplish this, SEAL has a variety of ways to simulate different atmospheric distortions, plus various equipment for measuring aberrations, and an array of mirrors for testing light correction. The adaptive optics that result use sensors to measure the distortion caused by Earth’s atmosphere alongside deformable mirrors that bend and correct the starlight, resulting in a much sharper image.

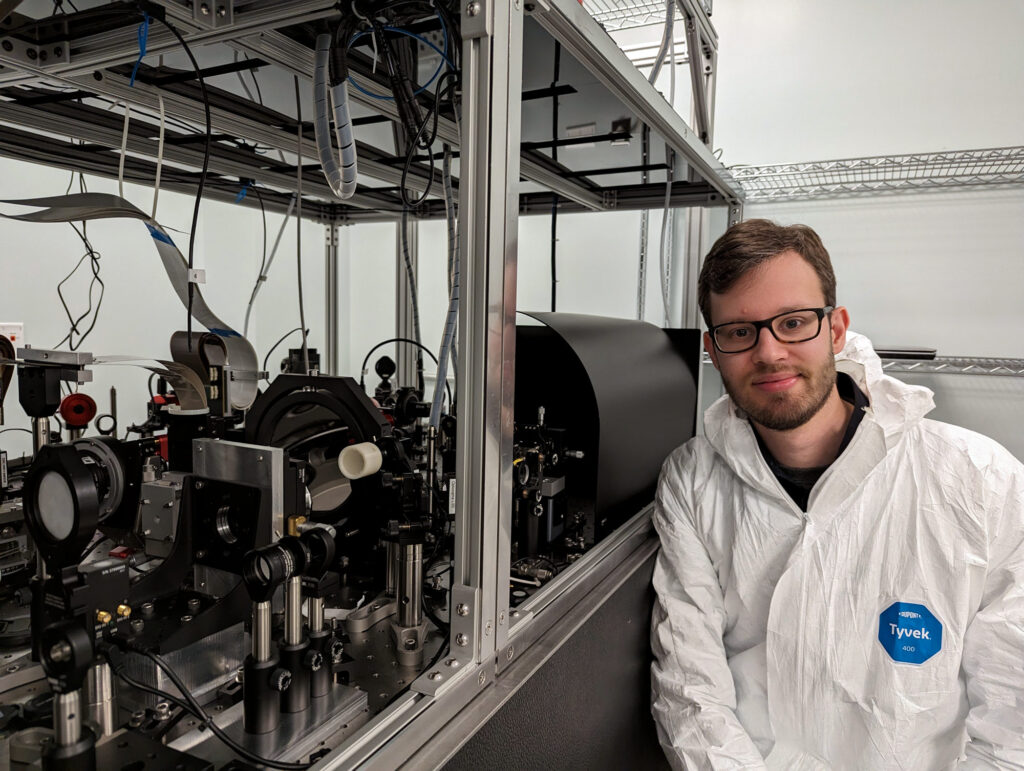

Jensen-Clem’s team rebuilt the SEAL testbed for better optical quality and performance last summer, just in time for postdoctoral researcher Emiel Por, astrophysicist and winner of the Heising-Simons Foundation’s 51 Pegasi b Fellowship, to join the group.

Using his expertise in astronomy and instrumentation, Por plans to further exoplanet science through novel inventions developed at SEAL, and mentor early-career researchers who are looking to break into the field.

A direct look

With a strong background in observational astronomy and instrumentation, Jensen-Clem was eager to join the Center for Adaptive Optics at UCSC after completing postdoctoral research at UC Berkeley. In particular, she was interested in finding ways to directly image Earth-like exoplanets using ground-based telescopes.

Almost all exoplanets discovered thus far have been found through indirect methods, such as observing the change in a star’s light when a planet passes in front of it. However, most exoplanets don’t transit because they aren’t aligned within our line of sight.

Direct imaging is a technique that holistically observes the exoplanet system by blocking the host star’s light, producing a “high-contrast” effect on its orbiting planet. In doing so, scientists can gain a better understanding of the planet’s atmosphere. That atmospheric light contains a spectrum of colors that characterizes the planet, and its constituents can point to the presence of specific molecules.

“The planet’s spectrum can tell us, for example, if there’s oxygen, nitrogen, or signs of life,” said Jensen-Clem. And by creating the right kind of tools, she could analyze an exoplanet’s distinctive nature more directly. It’s like trying to identify a person through the frizz of their backlit shadow (like the transit method) versus shining a light at them head-on (like direct imaging), she said; direct imaging will yield better results for exoplanet characterization.

In her application, Jensen-Clem proposed the development of a testbed that combined the prowesses of adaptive optics and high-contrast imaging called extreme adaptive optics. She toured the campus in 2018 during her interview, where she was invited inside UCSC’s Laboratory for Adaptive Optics (LAO). There, she spotted a giant granite table among its collection of detectors and mirrors, and knew that it would be the perfect spot for her idealized facility.

Prior to Jensen-Clem’s arrival, researchers used the table to test machinery for deformable mirrors due to its heavy weight, providing a low-vibration environment. Although LAO — founded in 2002 through a grant from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation — develops adaptive optics hardware as CfAO’s technical counterpart, the test facilities for extreme adaptive optics were much less complex during that time.

With LAO Director Phil Hinz’s permission, along with support from UCSC and a multi-campus astronomical research unit headquartered on campus called UC Observatories (UCO), Jensen-Clem and her assembled team built her testbed on that same granite table upon arriving in 2020. Jensen-Clem called their new research home the “Santa Cruz Extreme AO Lab.”

“For 25 years or so, Santa Cruz has been developing cutting-edge adaptive optics tech,” said Bruce Macintosh, the present director of UCO. “That got a big boost when Professor Jensen-Clem was hired.” Macintosh said UCO serves as the bridge between testing equipment at SEAL and actually putting it on a telescope.

Through SEAL, Jensen-Clem and her colleagues are paving the way for improved adaptive optics on telescopes such as those at Lick Observatory on Mount Hamilton in Santa Clara County, and W. M. Keck Observatory in Hawaiʻi. SEAL now attracts research scientists near and far to employ its specialized facilities for testing high-contrast imaging hardware, including Por.

Molding starlight

Before arriving at UCSC, Por studied astronomy and instrumentation at Leiden University and worked as a NASA Hubble Fellowship Sagan fellow at the Space Telescope Science Institute. In his early days as a graduate student, he wrote an open-source software package for high-contrast imaging. Serendipitously, Jensen-Clem relied on the same software package for her research as a postdoctoral scholar.

Now, Jensen-Clem is eager to serve as Por’s postdoctoral advisor as he creates more innovative extreme adaptive optics technology at SEAL. In fact, the main reason he chose to bring his work at UCSC is because of Jensen-Clem’s testbed.

“SEAL is a very, very modular testbed which follows a standard adaptive optics-style layout,” he said, noting how well the laboratory’s equipment and simulation techniques suit his research.

Like his advisor, Por is fascinated by the idea of constructing devices that help directly image exoplanets. He explains that while indirect methods work very well in detecting them, they only work for planets that orbit close to its host star, transit in our line of sight, or have extensive atmospheres. “As you go further out, there is very little that those methods can do,” he said. “That’s where direct imaging takes over.”

To improve direct imaging techniques, Por designs instruments known as coronagraphs that mask starlight to expose extremely faint planets and their atmospheres. And he isn’t just interested in suppressing starlight — Por seeks to “mold the starlight around an exoplanet” to better measure and analyze it.

One of his projects include building an advanced coronagraph for the Santa Cruz Array of Lenslets for Exoplanet Spectroscopy (SCALES), an instrument that combines the most successful methods of directly imaging smaller, older exoplanets close to their star at Keck Observatory on the big island of Hawaiʻi.

“We’re trying to collect light from an exoplanet that’s really close to its star in terms of how we see it in the sky, which means there’s a lot of glare from the host star,” explained Steph Sallum, an assistant professor of astrophysics and SCALES’ project scientist. “An instrument like the coronagraph Emiel is building will decrease that glare, which is really important for being able to take pictures of exoplanets.”

UCO director Macintosh agrees. “Emiel is one of the very best people in the world at designing special masks that block out that light from the star and let you see the tiny planet that’s left over,” he said. “At SEAL, he can use Professor Jensen-Clem’s testbed under controlled conditions to test how well he can block starlight.”

Additionally, Por will be inventing a new kind of coronagraph that utilizes photonics — a novel branch of technology that manipulates light through a path via total internal reflection. A traditional coronagraphic system can be as large as six feet in order to support its optical hardware; but a photonic coronagraph, such as what Por is designing, has the potential to miniaturize the whole system into the size of a flat chip at about an inch or less in length. This coronagraph will also be tested at SEAL, with the goal of implementing it at Lick Observatory.

“This emerging field of astrophotonics is really a revolution that’s happening right now, and new technologies like Emiel’s photonic-based coronagraph are some of the first representatives of that revolution,” Jensen-Clem said.

She is excited for the future of SEAL with Por on her team, who will not only steer the laboratory in a new direction, but also instruct the next generation of instrument scientists. This past summer, Jensen-Clem and Hinz hosted its annual AO Summer School, a practical workshop held at CfAO for early-career researchers filled with lectures and activities on adaptive optics. As one of the instructors, Por taught attendees how to perform simulations using specialized software. Considering how his high-contrast imaging software was used in similar activities in the past, Jensen-Clem deemed him a perfect addition to the school’s curriculum this year.

Although his time at UCSC has just started, Por is already spearheading an unprecedented era of adaptive optics and exoplanet science. With his innovations, scientists can gain another step forward in exoplanet characterization. “I bet we’ll be in a very different place in just five years from now than we are today,” said Jensen-Clem, “and I’m really excited to see where this takes us.”