Health

How optogenetics can put the brakes on epilepsy seizures

In what could one day become a new treatment for epilepsy, researchers at UC San Francisco, UC Santa Cruz and UC Berkeley have used pulses of light to prevent seizure-like activity in neurons.

In what could one day become a new treatment for epilepsy, researchers at UC San Francisco, UC Santa Cruz, and UC Berkeley have used pulses of light to prevent seizure-like activity in neurons.

The researchers used brain tissue that had been removed from epilepsy patients as part of their treatment.

Eventually, they hope the technique will replace surgery to remove the brain tissue where seizures originate, providing a less invasive option for patients whose symptoms cannot be controlled with medication.

The team used a method known as optogenetics, which employs a harmless virus to deliver light-sensitive genes from microorganisms to a particular set of neurons in the brain that can be switched on and off with pulses of light.

It is the first demonstration that optogenetics can be used to control seizure activity in living human brain tissue, and it opens the door to new treatments for other neurological diseases and conditions.

“This represents a giant step toward a powerful new way of treating epilepsy and likely other conditions,” said Tomasz Nowakowski, an assistant professor of neurological surgery at UCSF and a co-senior author of the study, which appears Nov. 15 in Nature Neuroscience.

Subduing epilepsy’s spikes

To keep the tissue alive long enough to complete the study, which took several weeks, the researchers created an environment that mimics conditions inside the skull.

John Andrews, a UCSF resident in neurosurgery, placed the tissue on a nutrient medium that resembles the cerebrospinal fluid that bathes the brain. David Schaffer, a biomolecular engineer at UC Berkeley, found the best virus to deliver the genes, so they would work in the specific neurons the team was targeting.

Andrews then placed the tissue on a bed of electrodes small enough to detect the electrical discharges of neurons communicating with each other.

When the brain is acting normally, neurons send signals at different times and frequencies in a predictable, low-level chatter. But during a seizure, the chatter synchronizes into loud bursts of electrical activity that overwhelm the brain’s casual conversation.

The team hoped to use the light pulses to prevent the bursts by switching off neurons that contained light-sensitive proteins.

Remote-control experimentation

First, the team needed to find a way to run their experiments without disturbing the tissue. The tiny electrodes were only 17 microns apart – less than half the width of a human hair – and the smallest movement of the brain slices could skew their results.

Mircea Teodorescu, a UCSC associate professor of electrical and computer engineering and co-senior author of the study, designed a remote-control system to record the neurons’ electrical activity and deliver light pulses to the tissue.

Teodorescu’s lab wrote software that enabled the scientists to control the apparatus, so the group could direct experiments from Santa Cruz on the tissue in Nowakowski’s San Francisco lab. That way, no one needed to be in the room where the tissue was being kept.

“This was a very unique collaboration to solve an incredibly complex research problem,” Teodorescu said. “The fact that we actually accomplished this feat shows how much farther we can reach when we bring the strengths of our institutions together.”

A working paper led by the UCSC Genomics Institute’s Braingeneers group describes how this software enables researchers to create and store data-dense recordings of neural activity. A user-friendly, open-source interface allows researchers with varying programming skills to analyze and visualize the recordings.

This provides a dramatically simplified solution for researchers interested in understanding neuronal activity in lab-grown tissues or modeling treatments for neurological disorders.

New insight into seizures

Optogenetics enables researchers to zoom in on discrete sets of neurons.

The group could see which types of neurons and how many of them were needed to start a seizure, and they determined the lowest intensity of light needed to change the electrical activity of the neurons in live brain slices.

The researchers could also see how interactions between neurons inhibited a seizure.

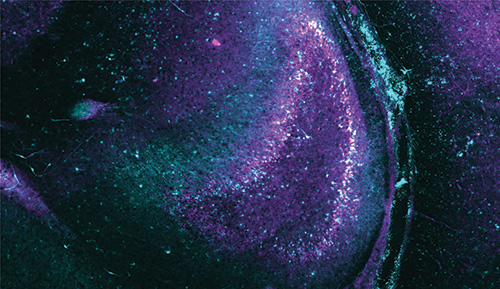

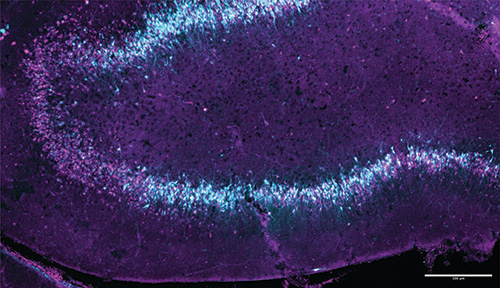

Another working paper reports on the detailed analysis of the study’s first recordings of a harmful feedback loop leading to a seizure-like event in a specific region of the brain called the “dentate gyrus.” From analysis of recordings of thousands of neurons with unprecedented fidelity at the precise onset of the seizure, the researchers gained new insights into what triggers a seizure.

Feedback-circuit connected neurons organize their activity first into wave-like patterns propagating in one direction, and then much larger wavelike patterns that propagate at 90 degrees to the initial waves, while they “phase lock” into synchrony. Further investigation with techniques like those from this project could help scientists further pin down exactly what biological mechanisms predispose these neurons to self-organize and become seizure-producing.

Edward Chang, the chair of Neurological Surgery at UCSF, said these insights could revolutionize care for people with epilepsy.

“We’ll be able to give people much more subtle, effective control over their seizures while saving them from such an invasive surgery.”

UC Santa Cruz researchers involved in this project include: Professors Sofie Salama, Tal Sharf, David Haussler, and Mircea Teodorescu; graduate student researchers Matthew Elliott, Alex Spaeth, Daniel Solis, Ash Robbins, and Drew Ehrlich; and postdoctoral scholars Jinghui Geng, Kateryna Voitiuk, and Jessica Sevetson.