Student Experience

Learning through participation

Barbara Rogoff has studied the collaborative method Mayan communities use to teach children for over 30 years

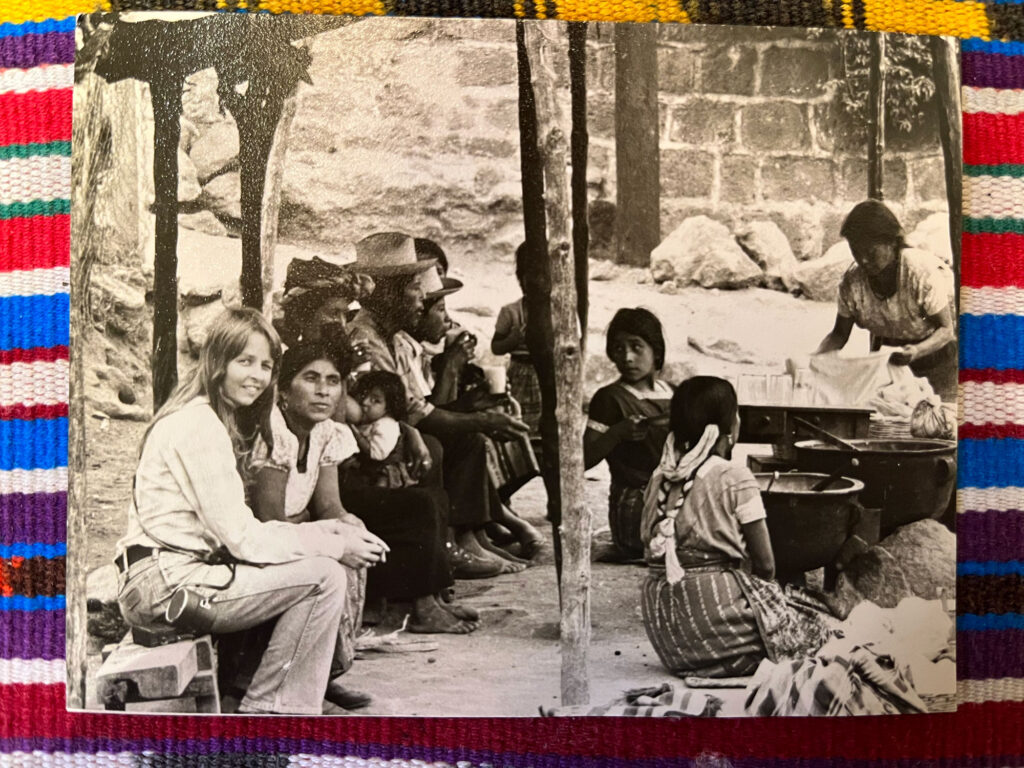

At the celebration event of the book Rogoff wrote, Developing Destinies. A Mayan Midwife and Town, with the sacred midwife Doña Chona Pérez (center) and colleague Marta Navichoc Cotuc (left)— Courtesy Domingo Yojcom.

“Give a man a fish and feed him for a day. Teach a man to fish and you’ll feed him for a lifetime,” so the proverb says. But perhaps figuring out how to fish on his own would be more beneficial for everyone involved.

After decades of studying how Mayan families raise their children, UC Santa Cruz psychologist Barbara Rogoff has found that learning through observation and collaboration is an effective way of raising capable, independent children and immersing them in their culture.

Rogoff, who is the UCSC Foundation Distinguished professor of psychology, has spent her career studying cultural differences in how children learn and how communities create everyday learning opportunities, with a focus on Indigenous-heritage communities in the Americas. She examines how their cultural practices shape learning through participation, collaboration, and observation in daily life. Her work has highlighted an unique approach to learning, called Learning by Observing and Pitching In (LOPI) to family and community endeavors, which emphasizes how children engage with and contribute to their families and communities as part of the learning process.

In November 2024, Rogoff and her graduate student Itzel Aceves-Azuara, now a psychology professor at California State University, Sacramento, published a study describing how collaborative learning in Mayan communities has changed over the past 30 years. We caught up with Rogoff to learn more about her decades of work in this field and what her new study suggests about how cultures are changing.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Q: What inspired you to study psychology within Indigenous cultures, specifically?

I think there are a number of things that influenced me from a young age.

For instance, when I was a child, I went to school in Australia from ages 5 to 6. Even though American and Australian cultures are similar, going to school there allowed me to notice contrasts between the cultures.

Another instance was when I was in eighth grade. I was not very happy taking home economics, but I could get out of taking home economics if I took Spanish, so that’s what I did. I think learning Spanish and connecting with cultural aspects of the language was a major impetus for my interest in studying Indigenous cultures.

And then in college, I became friends with a group of Chicano students who were very generous and patient in sharing their Mexican heritage with me. That helped me learn some aspects of how to be in their cultural community. It may have set me on the path for what I have spent my career studying.

Q: How did you become involved with studying the Indigenous communities in Guatemala?

In my third year of graduate school, one of my advisors asked me if I would be willing to work with him on a study in Guatemala. I agreed, and negotiated with him so I could spend half my time doing ethnographic research, which means observing and trying to qualitatively understand child development, and the other half of my time would be spent doing the cognitive testing that he was hiring me to do.

He was trying to find answers to questions such as, how do the children remember? Or, how do they understand quantity? But I was more interested in how they learn.

I noticed how skilled the children were at various everyday activities, such as weaving on a backstrap loom, which is a complicated skill the girls were very good at. Similarly, the boys were skilled in agriculture from a young age; it has so much science involved in it, and that really impressed me.

So, I asked mothers how they teach their daughters to weave, and they would say, “I don’t teach them, they learn.”

That was puzzling to me, because I thought, well, if the moms aren’t teaching them, how do they learn this very complex technology?

That question led me to the question that has directed the rest of my career, which is: How do kids learn in such a situation where they’re not being formally taught?

Q: Can you share more about the projects you did with the communities in Guatemala over the decades?

There’s been a lot of them but there was one study that was a central one. I wanted to find out how mothers in different cultures help their children learn.

We visited the homes in four communities: San Pedro in Guatemala, a middle-class community in Salt Lake City, Utah, a tribal community in North India, and then a middle-class community in Turkey. We interviewed mothers about child rearing and the children’s daily routine and we asked them to show their young children how to operate some novel objects, such as an embroidery hoop with a clamp, or a jumping jack puppet. We then observed how the mothers interacted with and helped their toddler learn about the new objects.

What we found is that the middle-class families who we interviewed in Utah and Turkey would often organize their interaction like a lesson. They were trying to motivate the children’s involvement with mock excitement, saying, “Oh, look, look, sweetie, look at this”, using a voice that adults do not use with each other, but to get the child excited about watching, and by giving them vocabulary lessons. They would test the children by asking things like, “Oh, where’s its eyes? Where’s its hat?” Oftentimes, they would overrule what the child actually wanted to do with the object. We found they would either pay attention to their children, or pay attention to the interview.

In the Mayan community, we didn’t see much of those things. What we saw was that the mothers were in a posture ready to help the child, and very subtly would help the child while simultaneously doing other things. The mothers were able to manage the interview without interrupting what they were doing with the toddler, and help the toddler without interrupting what they’re saying in the interview. These observations were similar to what we saw in India, too.

Q: Your studies led you to describe a specific type of learning, called Learning by Observing and Pitching In (LOPI). Can you explain this concept?

The term describes the way of life that I observed, and how the children learn by being a part of it. In Learning by Observing and Pitching In to family and community endeavors, children are included as a contributing member, even the youngest children.

There are seven key facets to this way of learning, with the central one being that the kids are included as contributors in family and community events. The interactions with children are collaborative, rather than someone telling the child what to do, like we often see in European-American families. The idea of learning in Mayan culture has more to do with learning to be a contributing member of the community, and learning skills as well as innovating for the benefit of the community.

The parents trust the children to be involved and learning. That contrasts with what we’ve seen in European American middle-class families, where kids are assumed at age two not to be capable of helping, and parents often try to exclude them from the situation.

In a study with Mexican heritage moms in Santa Cruz, the moms emphasized children’s initiative and learning to be part of the group. One said, “Well, it’s not like the sweeping by two-year-olds is really getting the floor that clean, but they’re learning to be a part of things.They’re learning how to be part of the circle of the family.”

Q: You recently published a study comparing how learning within Indigenous families had changed over the last 30 years. What were your findings?

Just before Covid, my former graduate student, Itzel Aceves-Azuara, and I interviewed the same moms from the families that I worked with 30 years ago in Guatemala, and this time we looked at how their grown daughters interacted with their own children, that is, the grandchildren, to see if this way of learning continues through a generation.

We saw a few changes, one of them being that 30 years ago, the three people in the family were interacting together almost all the time. Now, that kind of inclusive collaboration was happening only about half the time. It was more often that two people in the family were engaged together and the other was separate. One important thing that did not change, however, is that their interactions remained harmonious.

We did this same study with European American middle-class families and found that 21% of the time, the families engaged with resistance to each other, so there was often some sort of conflict.

We found that number to be much lower in the Mayan community, where 30 years ago there was conflict in only about 5% of the interactions, and we found that to still be true in this next generation. So, they’ve managed to maintain a really important cultural practice but at the same time, they changed in the extent to which everybody was included in the interactions.

The Mayan families we worked with were quite pleased to learn that our study showed that they’ve maintained such harmonious relationships. They taught me a new phrase in Tz’utujil, their native language: “k’o rxajaaniil,” which means “it has sacredness.” They use that phrase all the time, especially when the kids are about to start fighting. With that little phrase, they’re telling the kids to be harmonious.

Q: What are you working on now? And what are your next steps from here?

Itzel Aceves-Azuara and I plan to continue studying how the families have changed their ways of interacting over the years, but now we’re looking at the difference in attentiveness – how much the older child is paying attention to what’s going on – and the ways that the mothers talk to the kids.

I’m also working on a historical photo archive project. I inherited many important, historical photographs of the Mayan community in Guatemala that were taken by an anthropologist couple back in 1941, but they’re in the form of negatives and contact sheets. So together with some local people, we are forming a local committee and figuring out how to get them developed and how to make them accessible to the local people.

Q: What advice would you give to someone studying about the cultural impacts on child development or someone starting out in this field of study?

I think it’s really important to be embedded in the community that one is studying, forming relationships with people and having your eyes open to things that you didn’t expect. That’s where you’ll learn the most.

That’s different from a lot of methods that are used in this field, where people often do experiments with a hypothesis. They already think they know the answer in some sense – either A or B, but they’re not even considering that it could be C, D, E, or F.

Context is important, so the advice I would give to the person who’s trying to understand child development is to understand the context by being there, by being a part of it — by practicing LOPI themselves.