Climate & Sustainability

A Justice-Focused Perspective on the Clean Energy Transition

Chris Benner investigates lithium extraction at the Salton Sea, and what it means for community groups and the future of clean energy.

A sign on the shore of the Salton Sea mocks the lithium industry (Photo: Chris Benner).

Chris Benner gets around, and not just by bike. About a decade ago, before he arrived at UC Santa Cruz, the sociologist and environmental studies professor worked to help produce reports and make recommendations for California’s Energy Commission and the Bay Area Metropolitan Transportation Commission, which inform some of his current research. In the meantime, he also studied housing shortages, solidarity economics, the plight of gig workers, and more.

Benner’s new book Charging Forward, is a timely exploration of one California region’s role in the growing production of electric vehicles, lithium extraction, and a “just transition” to a greener economy. Benner and his coauthor, Manuel Pastor, a sociology professor at the University of Southern California, highlight the valuable promise of a US-based lithium source, but warn of the potential for environmental degradation and labor exploitation. The book marks a significant step in Benner’s wide-ranging, interdisciplinary research, as he brings his justice and equity-oriented perspective into the field of climate action and sustainability.

“My work aims to understand structures of economies, and particularly how technological change is shaping economic well-being and economic access, and equity dimensions of that. Economic justice is the thread that ties all of those together,” said Benner, who is also director of the UCSC Institute for Social Transformation.

A modern gold rush

Energy demand and consumption is rapidly evolving and expanding throughout the United States and much of the world — a trend that will continue if climate mitigation goes well and oil and gas consumption drop. Tesla alone delivered about 1.8 million electric vehicles last year, and although sales have dropped recently, the company expects those numbers to soar eventually to tens of millions. At the same time, state governments continue building new wind farms and solar plants, while residential solar panels become increasingly popular.

All of these technologies, and especially batteries, need huge quantities of key metals. That means the energy transition will come with continually rising demand for critical minerals like lithium, cobalt, manganese, nickel, copper, and rare earth elements.

For some time to come, the world desperately needs lithium for lithium-ion batteries, the demand for which is rising. Because of this, some analysts foresee a shortage in the near future, as demand for lithium could grow tenfold.

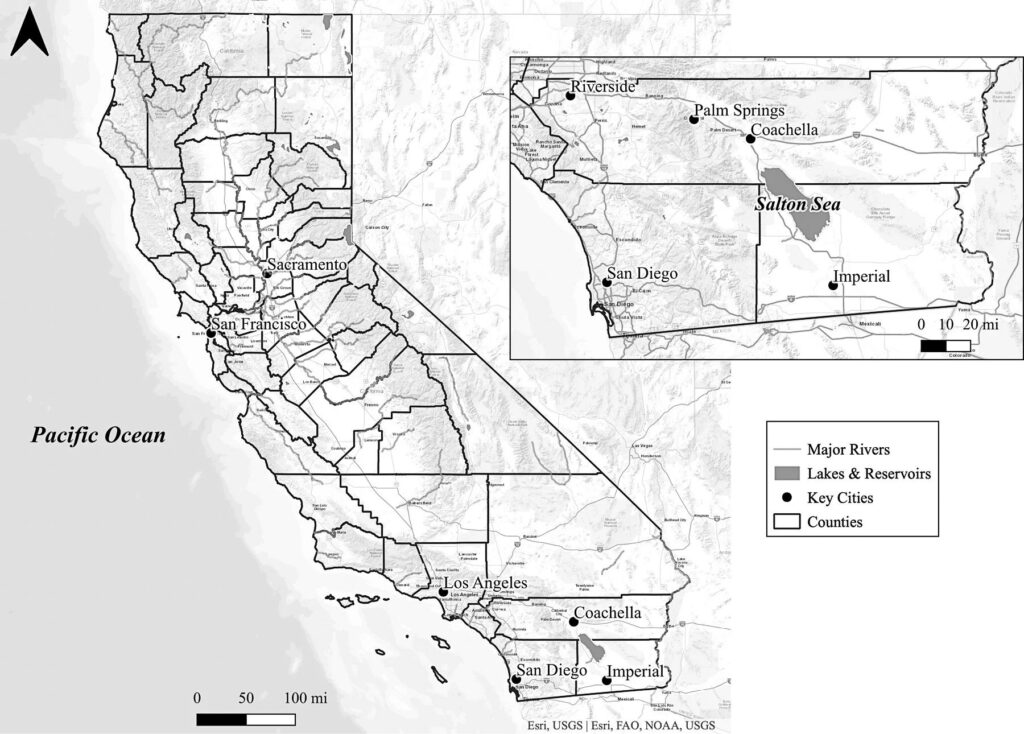

Currently, lithium predominantly comes from hard-rock mining operations in Australia or brine evaporation ponds in an area known as the Lithium Triangle — the arid, mountainous regions of Chile and Argentina. But groups in southeastern California seek to develop a new source, extracting lithium in the economically struggling and environmentally sensitive Salton Sea region.

The Salton Sea is a land-locked lake filled with salty water in the middle of the desert, about 100 miles northeast of San Diego. The lake formed in the early 1900s when floodwaters breached a canal after the Colorado River was redirected, following a deal with Mexican president and dictator Porfirio Díaz. In the 1950s, popular tourist venues popped up in the desert, including those visited by The Beach Boys, Frank Sinatra, and other artists.

It’s a compelling place that quickly piqued Benner’s interest, packed with myriad local stories, not just about the tragically shrinking, contaminated lake, but also about the people. “Come for the analysis, stay for the story,” he said.

Benner and Pastor’s success with work involving economics and equity throughout California caught the attention of Silvia Paz, executive director of Alianza Coachella Valley, a nonprofit group advocating for the region’s economy and environment. She approached the pair in 2020 to generate an equitable economic vision for the area on the northern side of the Salton Sea, resulting in two reports.

When Paz was soon afterward appointed by the governor to serve as chair of the Lithium Valley Commission, a state legislature-created group tasked with developing lithium opportunities in California, she again tapped Benner and Pastor for their expertise. She had them testify to the Commission on the prospects, opportunities, and challenges of lithium extraction in the region, and incorporated their findings along with other expert and community testimonies in a public report delivered to the legislature in 2022.

“We came to increasingly appreciate the importance of lithium for that region, but also to see it as a microcosm for broader global issues as we transition from extracting fossil fuels to extracting minerals all around the globe,” Benner said. That engagement with Paz ultimately informed Benner’s continued research in that area, including his new book.

Rather than wrestling lithium from huge evaporation ponds filled with brines from underground, as is done in South America, authorities in the Salton Sea region (spanning territory in southern California’s Imperial and Riverside Counties) aim to extract it from the hot brine sitting thousands of feet beneath the ground neighboring the lake, brought to the surface by drilling. Lithium mining companies want to work with the existing geothermal energy businesses in the area, as their geothermal drilling is already bringing mineral-rich brine to the surface that could be deployed to produce lithium.

As Benner and Pastor published their book, multiple companies have taken initial steps toward commercial lithium projects, while facing varying degrees of opposition. Within a couple years, Californian lithium may become a reality, if the companies’ plans come to fruition. “The region has become ground zero in California’s new ‘white gold rush’ — the race to extract lithium to power the rapidly growing EV and renewable energy storage market,” Benner and Pastor wrote.

An equitable solution

Mining companies advertise the proposed direct extraction method as the cleanest, greenest way to get lithium. The effort could also promise some economic relief, through jobs and economic development, to the relatively impoverished community.

But some local nonprofit groups, like Comite Civico del Valle, with whom Benner and Pastor have been in contact during the course of their work, have drawn attention to labor and environmental concerns. The groups have also organized coalitions, such as Valle Unido por Beneficios Comunitarios, campaigning to negotiate mandatory community benefit agreements about unionized jobs, hiring conditions, and wages, Pastor said.

Meeting and engaging with community-based groups, as well as environmental, labor, and other organizations has become a big part of Benner’s research. In this work, he and Pastor support the concept of “green justice,” reminding audiences — whether they’re local groups, policy makers, or others — that not everything that appears green is good. Anyone developing a new kind of energy needs to be mindful of local social and environmental concerns, they argue in their book.

Over the course of this thread of research, Benner has been exploring how this shift to clean energy and transportation could become a just transition that benefits a broad swath of society. He considers three sets of jobs, including labor-friendly construction jobs, jobs for maintaining and operating facilities, and the many more jobs beyond mineral extraction, including those involved in EV battery manufacturing plants and assembling the electric vehicles.

For Benner, those additional jobs are crucial, and they’re lacking in many places that provide critical minerals to the industry, like Democratic Republic of the Congo and copper-producing Chile. He makes the case that the Imperial Valley has good transportation infrastructure, a large labor force, and lower land and energy prices than the rest of California, so it’s economically viable. “We should push for that kind of manufacturing to happen there, to get more of an economic benefit from the industry,” he said.

James Blair, an environmental anthropologist at California State Polytechnic University, Pomona, who leads the Lithium Valley Equity Technical Advisory Group for Comite Civico del Valle, describes Benner and Pastor as “prolific researchers” who have established partnerships with groups from the region, such as Alianza based in Coachella Valley. “I appreciate how they’ve been able to demonstrate the need for strong community benefits through their demographic research as well as the sweeping overview of labor and economic analysis of the battery supply chain and the energy transition in the US,” he said.

It’s a challenging balance Benner and Pastor are trying to achieve, Blair said, supporting the interests of corporations and developments while also suggesting that community organizations have the capacity to negotiate for their own interests. Also concerning is the proposed lithium extraction’s water consumption, air quality and hazardous waste impacts, Blair said, which Comite and other groups have drawn attention to. “One thing that’s important not to brush over is tribal cultural resources,” he added. “There are sacred sites in this area that need protection.”

Benner and Pastor’s book mentions the Torres Martinez Desert Cahuilla Indians, who lost half their reservation when the Salton Sea was created in the first place. Others, like the Kwaaymii Laguna band, the Kumayaay, the Agua Caliente band of Cahuilla Indians, and the Quechan Tribe, have been vocal in public comments and legal disputes about the lack of tribal consultation and consent for these projects.

Sustainable partnerships

Benner and Pastor have collaborated since the late 1990s on numerous projects, starting with providing research for a living-wage campaign in San Jose. They’ve coauthored five previous books, as well as an LA Times op-ed last fall arguing that the Imperial Valley population shouldn’t be exploited during this potential lithium boom.

Speaking about their longtime collaboration, Pastor said, “I think partnerships in the long haul depend on trust, and that’s trust in someone’s skill, in their generosity, in their values. And skill, generosity, and good values — that’s Chris Benner.”

Through their research and advocacy, Benner and Pastor have been “an important and influential voice,” Blair said. By studying the situation, working with local groups, and publishing reports early in the process, before lithium mining has begun, Benner and his colleagues have been able to argue for the need for it to benefit people living there, especially in disadvantaged communities.

Organizations in the area and legislators began taking note of Benner’s and Pastor’s book within a few months of its publication. State Senator John Laird, for example, told the researchers he appreciates their work, but believes the impact of state funds on environmental restoration was more significant than what Benner and Pastor portrayed. Ryan Kelley from the Imperial County Board of Supervisors also has been in communication with Benner and Pastor about their work, as he is interested in moving forward with lithium development in his county.

As long as the lithium resources in Imperial Valley interest political and commercial leaders there, Benner will continue asking his driving question: “Are steps being taken throughout the process to minimize environmental impact and maximize the benefit to the local community?” To Benner, such critical questions are relevant to any highly-valued mineral throughout the world, as humanity haltingly moves toward clean energy.