Campus News

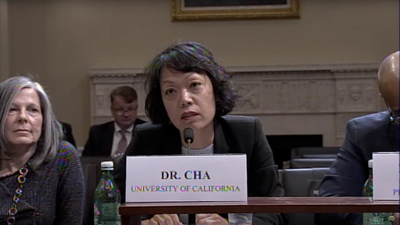

J. Mijin Cha testifies on solutions to energy poverty before congressional subcommittee

Assistant Professor of Environmental Studies J. Mijin Cha shared her insights on solutions that could make electricity more affordable for low-income families across America.

Screenshot

Assistant Professor of Environmental Studies J. Mijin Cha testified during a legislative hearing of the U.S. House of Representatives Subcommittee on Energy and Mineral Resources on Dec. 12, to discuss energy poverty and share her insights on solutions that could make electricity more affordable for low-income families across America. During her testimony, Cha recommended a three-pronged approach.

“To address the root causes of energy poverty, we must, one, reintroduce the ban on oil exports and expand it to include a ban on fracked gas exports to keep oil and gas extracted in the U.S. in the U.S.; second, we must expand current federal assistance programs that provide assistance to struggling households, such as the Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP) and the Weatherization Assistance Program (WAP); and third, we must plan for and advance a managed decline of fossil fuel extraction and use,” she said.

Cha had been invited to testify on H.R. 5482, a bill introduced by Rep. Harriet Hageman, R–Wyo., The proposed bill would commission a report to congress on issues of energy affordability, require estimates of how any future bills or resolutions related to federal management of energy resources might affect household energy costs, and impose new limits on how federal agencies can manage land and energy resources, especially fossil fuels.

In particular, the bill would require that, before federal agencies can make any decisions about energy resource extraction, pipelines, or transmission, they must undertake additional studies at the request of companies or others who want to develop the energy resources. These studies would focus specifically on any possible benefits of the proposed project for energy costs or jobs but would not include any negative consequences, such as increased localized pollution or greenhouse gas emissions released.

In opening remarks for the legislative session, Subcommittee Chairman Pete Stauber, R-Minn., said the bill is part of an “all of the above” energy development agenda being pushed by Republicans that he believes will “help increase domestic energy production and reduce energy costs for American families.” He blamed rising energy costs on the Biden Administration and said the bill is an effort to “hold this administration responsible for their policies that are raising energy costs and burdening at-risk communities across our country.”

Subcommittee Ranking Member Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, D-N.Y., questioned the bill’s logic during her opening remarks, pointing out that home energy costs in the U.S. have continued to go up at a time when American oil and gas production is at a record high. She said the bill’s requirements for federal agencies to produce “one-sided” benefits reports that don’t consider costs or risks is intended to slow down any federal efforts to transition away from fossil fuels, and she accused the bill of “exploiting the language of poverty in order to enrich private oil and gas interests.”

During her testimony, Cha commended the committee for recognizing the importance of energy poverty, citing U.S. Energy Information Administration data from 2020, which found that roughly one-third of U.S. households struggled to pay their energy bills or kept their homes at unsafe temperatures because of cost concerns. But, she told the committee that the proposed bill’s specific focus on increasing fossil fuel production “is counter to combating energy poverty.”

Cha said that since 2015—when Congress repealed a ban on crude oil exports that had been in place for 40 years—the U.S. has become a net exporter of petroleum. Exports of both crude oil and liquified natural gas (of which the U.S. is also a net exporter) have been found to result in increased domestic costs, because exports tie prices to global markets, rather than just domestic demand. For this reason, Cha says the bill’s focus exclusively on increased energy production “does nothing to reduce energy prices,” but ending exports of these resources could actually reduce domestic costs and “ensure American resources benefit Americans.”

Moreover, energy bill payment assistance programs, like LIHEAP, and home energy efficiency improvement programs, like WAP, tackle the issue of energy poverty far more directly, Cha explained. Energy efficiency gains from weatherization can reduce heating bills by up to 30%, and bill assistance through LIHEAP “could be a lifeline for all families in need,” she said. But at current funding levels, LIHEAP can only serve about a third of the households that are eligible for the program.

“If cost is a concern, expansion of LIHEAP and WAP could be funded by repealing the tax credits and subsidies that oil and gas industries receive,” Cha recommended. “Conservative estimates calculate that oil and gas companies currently receive $20 billion a year in financial subsidies. These subsidies dwarf the amount allocated to LIHEAP: currently just $3.6 billion for the fiscal year 2024.”

Cha also advised the subcommittee to keep sight of the fact that climate change, which is primarily driven by the use of fossil fuels, is ultimately the biggest threat to the health and safety of low-income communities. Heat and extreme weather events tied to climate change can also increase home energy demand—resulting in higher bills—and can damage electricity grids, leading to blackouts and instability in electricity service that puts all Americans at risk. For all of these reasons and more, Cha said the U.S. must phase out the extraction and use of fossil fuels, and H.R. 5482 runs counter to that goal.

“To stave off the worst impacts of the climate crisis, we must have a managed and orderly decline of fossil fuel extraction and use,” she concluded. “A timeline with set production reduction targets and resources for transition will provide stability and certainty for markets to adapt and provide stability and certainty for workers and communities.”