Campus News

One of the planet’s most important carbon sinks is revealing its secrets

New research clarifies how tiny organisms in the Southern Ocean play an outsized role in moderating Earth’s climate.

Screenshot

The Southern Ocean plays a central role in moderating the rate of climate change, absorbing an estimated 40% of the total amount of human-generated carbon dioxide emissions and 60-90% of the excess heat trapped by greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. Understanding how the Southern Ocean absorbs carbon dioxide is one of oceanography’s top priorities, but remote, harsh conditions of the Southern Ocean challenge scientists’ ability to accurately characterize how carbon cycles through the ocean and atmosphere.

A new study, published April 26 in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, quantifies key aspects of the biological processes that influence the Southern Ocean carbon sink. The “biological pump,” where carbon is used by organisms at the surface and transferred to ocean depths, away from contact with the atmosphere, is a critical process in ocean carbon cycling.

First author Yibin Huang worked on the study as a postdoctoral researcher in ocean sciences at UC Santa Cruz, together with corresponding author Andrea Fassbender, a research scientist at NOAA’s Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory and adjunct professor of ocean sciences at UCSC, and coauthor Seth Bushinsky at the University of Hawaii at Mānoa.

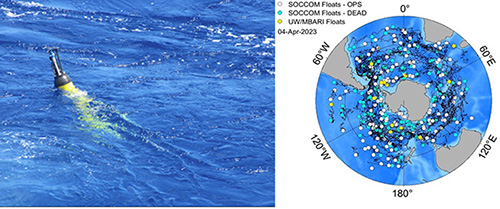

The researchers examined data collected from more than 60 autonomous profiling floats over 10 years to quantify for the first time the role that tiny phytoplankton play through their creation of different types of biogenic carbon. Each type of biogenic carbon has a different impact on carbon export and on the exchange of carbon dioxide between the atmosphere and ocean.

Understanding the Southern Ocean’s carbon cycle is critically important because a change in the rate at which biogenic carbon is stored in ocean waters could result in more carbon dioxide remaining in the atmosphere, which could potentially affect the rate of climate change.

Huang, now at the NOAA Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory in Seattle, said that simultaneously monitoring the three different types of carbon produced by biological activity has posed a longstanding problem for oceanographers. The three types of carbon—particulate inorganic carbon, particulate organic carbon, and dissolved organic carbon—interact in a complex set of balancing relationships that determine how much carbon is absorbed by the ocean and how much is released to the atmosphere. Due to the complexity of traditional methods of measuring the amount of carbon exchanged between types of carbon over a specified time, he said, scientists have tended to treat the total carbon production as a black box.

“Our study applies a recently developed method for estimating the production and export of distinct biogenic carbon pools in a cost-effective way and at ocean basin scales to monitor how marine ecosystems function and their response to future climate change,” Huang said.

In the Southern Ocean below 35° south latitude, the interaction of physical and biological processes shapes regional biogeochemistry and influences the global ocean interior. Prevailing upwelling south of the Antarctic Circumpolar Current brings deep waters rich in dissolved inorganic carbon into contact with the atmosphere. The deep waters are also rich in nutrients, which fuel biological activity that peaks during spring and summer. Phytoplankton consume dissolved inorganic carbon, with some species using it to make their exoskeletons, and subsequently transport it to depth when they die.

While plankton flourish in this rich, cold water, they can’t fully use available nutrients and the dissolved inorganic carbon brought to the surface during upwelling. Some of the dissolved inorganic carbon is outgassed to the atmosphere locally. The unused nutrients are subsequently transported toward the equator via large-scale ocean circulation, fueling a large fraction of the biological production in the subtropics and tropics. The seasonal pattern of carbon cycling in the Southern Ocean is also shaped by the slowdown in phytoplankton growth during the winter.

The new paper focuses on quantifying the amount of dissolved inorganic carbon used by these tiny organisms, and how the natural process of carbon export influences the modern air-sea exchange of carbon dioxide.

The researchers found that organic carbon production captures roughly 3 billion tons of carbon per year, which is equivalent to about one quarter of total human emissions, while particulate inorganic carbon production diminishes carbon dioxide uptake by about 270 million tons per year. Differences in the amount of each type of carbon produced from north to south across the Southern Ocean influence how the biological pump impacts local air-sea carbon dioxide exchange.

If the amount of carbon fixed by these phytoplankton decreased by 30%, the Southern Ocean would release carbon dioxide instead of absorbing it, the scientists said.

The significant role played by phytoplankton in the modern Southern Ocean carbon sink suggests that understanding year-to-year variability in biogenic carbon production is key to understanding the overall Southern Ocean carbon sink, Fassbender said.

“Expanding persistent year-round observations from biogeochemical profiling floats would serve as a cost-effective way to monitor the biological pump throughout the Southern Ocean and globally,” she said.

The study was primarily supported by a National Science Foundation grant at UC Santa Cruz.