A few years ago, UC Santa Cruz Assistant Professor of Astronomy and Astrophysics Kevin Bundy became intrigued by the potential of photonic devices, which can detect and manipulate light on small scales, to miniaturize the methods used to capture information about objects in the night sky.

Excited by the possibility of this astrophotonics technology, he reached out to Holger Schmidt, distinguished professor of electrical and computer engineering and an expert in the field of photonics, to open a conversation about the potential for collaboration.

Now, the two researchers have won an NSF grant that will allow them to pursue this emerging technology of making spectrometers on a chip – tiny devices for separating and measuring light at ultraviolet, visible, and infrared wavelengths to to study the properties of objects in the sky, including their composition and distance. They believe that this technology can not only enable advances in astronomy when used as part of telescope instrumentation, but can be leveraged for a wide variety of applications across fields such as chemical analysis, environmental monitoring, and biosensing.

“There's a lot of technology now that can be brought to bear in taking these spectrometers – these color analyzers – and shrinking them down from about the size of a car to something much more compact, and in some senses more powerful,” Schmidt said.

Spectrometers-on-a-chip have the potential to be very impactful in that sizing down the technology to split and detect wavelengths of light can mean many can be packed on to one single telescope, making it possible to one day collect spectra from tens or even hundreds of thousands of celestial sources simultaneously.

Their small size also means they can be produced at a lower cost, transported more easily, and integrated with other components to create a device with a wide range of functionality – all of the benefits we typically associate with the miniaturization of tech.

“The general benefit is just the ability to collect a lot more information from the sky a lot more powerfully and cheaply,” Bundy said. “You can imagine putting these devices on a satellite or on a balloon, because they would be so much smaller and lighter.”

But there are two main challenges the researchers must address before their spectrometers-on-a-chip can be successfully implemented in telescopes and potential other applications.

The first is the issue of optimizing the chip itself, which includes making them more efficient, making sure they can record and provide the right information about the light they detect, learning how to integrate them so they can pack multiple chips side-by-side on one device. The researchers need to operationalize the chips so that they can become a robust component of a larger instrument, such as one mounted on a telescope, and not just a device that is studied in the lab.

The other main challenge is to couple the light received through the telescope into the miniature spectrometers. Because of Earth’s atmosphere, ground-based telescopes never produce a perfectly stable image of a star, but instead the star is always wobbling slightly in the image. This effect is not conducive to photonic spectrometers, which work best when the light they receive is pure and undisturbed. This requires the scientists to think innovatively about how to best feed light from the telescopes to the spectrometers.

“That challenge is the reason why this is an interesting problem, and it’s one of the reasons we don't have this technology on existing telescopes,” Bundy said.

Bundy believes there is growing momentum for this area of research, and that it can be of great benefit to ongoing efforts within the astronomy community. For example, a current project at the Rubin Observatory will capture images of and catalog billions of objects in the night sky. Current technology only allows scientists to capture the spectra of 5,000 objects at a time, making a project to follow up on the images captured and measure spectra at this scale nearly impossible. But Bundy hopes that the new devices the UCSC researchers develop will make this affordable and feasible.

“For cosmology and galaxy formation, I don't see another way to continue our forward momentum in terms of better instruments in the 10 to 20 year timescale,” Bundy said. “In about ten years, there has to be some technological transformation, or we're kind of stuck. I think there's going to be growing interest in making this work.”

Schmidt’s lab will focus on designing and testing the miniature spectrometers, with fabrication of the devices spearheaded by collaborators at Brigham Young University. Bundy’s group, led by graduate student Matt DeMartino, will establish the requirements for the device in order to optimize and test its performance.

“I think this will be the first step in hopefully a broader set of programs and projects that combine photonics and astronomy,” Schmidt said.

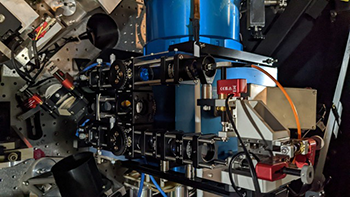

The researchers will work to integrate their miniaturized spectrometers onto the telescope at Lick Observatory, which is managed by UC Observatories and located close to Santa Cruz. In the near future, the team hopes to test their devices on the telescope there, meaning the three-meter, nearly 80-year old device can play an important role for developing cutting-edge astronomical instrumentation.

The grant will also fund several STEM outreach programs taken on by the researchers. The researchers will run experiments related to photonics as part of the Seeds Spoon Science program, which teaches local school children and their families science through gardening. They will also participate in the UC LEADS and CAMP programs which sponsor promising students from underrepresented groups, and continue successful outreach programs at local elementary and middle schools.