Campus News

JWST makes first unequivocal detection of carbon dioxide in an exoplanet atmosphere

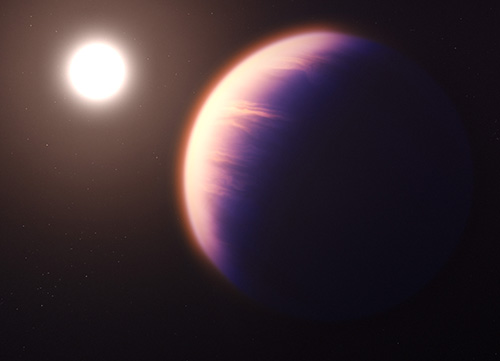

UCSC astronomer Natalie Batalha leads a team that detected carbon dioxide in the atmosphere of the exoplanet WASP-39b using the James Webb Space Telescope.

For the first time, astronomers have found unambiguous evidence of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere of an exoplanet (a planet outside our solar system).

The discovery, accepted for publication in Nature and posted online August 24, demonstrates the power of the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) to deliver unprecedented observations of exoplanet atmospheres.

Natalie Batalha, professor of astronomy and astrophysics at UC Santa Cruz, leads the team of astronomers that made the detection, using JWST to observe a Saturn-mass planet called WASP-39b which orbits very close to a sun-like star about 700 light-years from Earth.

“Previous observations of this planet with Hubble and Spitzer had given us tantalizing hints that carbon dioxide could be present,” Batalha said. “The data from JWST showed an unequivocal carbon dioxide feature that was so prominent it was practically shouting at us.”

Carbon dioxide is an important component of the atmospheres of planets in our solar system, found on rocky planets like Mars and Venus as well as gas giants like Jupiter and Saturn. For exoplanet researchers, it is important both as a gas they are likely to be able to detect on small rocky planets and as an indicator of the overall abundance of heavy elements in the atmospheres of giant planets.

“Carbon dioxide is actually a very sensitive measuring stick—the best one we have—for heavy elements in giant planet atmospheres, so the fact that we can see it so clearly is really great,” said coauthor Jonathan Fortney, professor of astronomy and astrophysics at UCSC and director of the Other Worlds Laboratory.

Stars and gas giant planets are made primarily of the lightest elements, hydrogen and helium, but the abundance of heavier elements—what astronomers call “metallicity”—is a critical factor in planet formation, Fortney explained.

“The ability to determine the amount of heavy elements in a planet is critical to understanding how it formed, and we’ll be able to use this carbon dioxide measuring stick for a whole bunch of exoplanets to build up a comprehensive understanding of giant planet composition,” he said.

Batalha’s team observed WASP-39b as part of a JWST Early Release Science program to study transiting exoplanets. A transiting planet passes in front of its star as viewed from Earth, enabling astronomers to analyze the starlight that passes through the planet’s atmosphere, where gases like carbon dioxide absorb certain wavelengths of light.

Using the Near Infrared Spectrograph (NIRSpec) on JWST, the team obtained a high-resolution “transmission spectrum” showing the light transmitted through WASP-39b’s atmosphere separated into its component wavelengths. Batalha said the data yielded “exquisite light curves” and showed that the NIRSpec instrument is exceeding expectations for transmission spectroscopy. This bodes well for observations of small rocky planets, which are expected to have carbon dioxide in their atmospheres (when they have atmospheres) but won’t give as strong a signal as a giant planet like WASP-39b.

“This detection will serve as a useful benchmark of what we can do to detect carbon dioxide on terrestrial planets going forward,” Batalha said. “It’s the most likely atmospheric gas we’ll detect with JWST in terrestrial-size exoplanet atmospheres.”

In addition to carbon dioxide, the researchers detected another interesting feature in the spectrum of WASP-39b that they have not yet identified. “It’s a mystery feature for now,” Batalha said. “In this paper, we focused on a narrow range of infrared colors—this is only a preview of the features we expect to see in the full spectrum.”

Fortney noted that WASP-39b appears to have a similar composition to Saturn. Saturn’s metallicity is 10 times that of the sun, and WASP-39b also seems to be enriched in heavy elements by about 10 times relative to the sun.

“That’s super interesting, and we would love to know if all Saturn-mass planets have the same metallicity,” he said. “It was exciting to see this in another system, because we didn’t know what to expect when we went from the planets in our solar system to the atmospheres of exoplanets.”

Located in the constellation Virgo, WASP-39b is more than 20 times closer to its star than Earth is to the sun. Although it is about the same mass as Saturn, it is less dense and about 50 percent larger, probably due to heating from being so close to its host star. Previous observations showed it to have relatively clear skies, making it a good target for transmission spectroscopy.

When the first data from JWST were released in July, the UCSC exoplanet researchers were hosting 45 visiting astronomers for the Other Worlds Laboratory’s annual Exoplanet Summer Program. “We were all huddled around the laptop getting our first look at the spectrum and marveling at it,” Batalha said. “It’s a tremendous, almost euphoric feeling, seeing something for the first time that no other human has seen before—that’s what science is all about.”

In addition to Batalha and Fortney, the JWST Transiting Exoplanet Community Early Release Science Team includes Xi Zhang, associate professor of Earth and planetary sciences at UCSC, postdoctoral fellows Aarynn Carter and Kazumasa Ohno, graduate student Sagnick Mukherjee, alumnus Zafar Rustamkulov (now a graduate student at Johns Hopkins University), and former postdoctoral fellow Natasha Batalha (now at NASA Ames), as well as a long list of coauthors around the world.

The James Webb Space Telescope is an international program led by NASA with its partners, the European Space Agency and the Canadian Space Agency, and is operated by the Space Telescope Science Institute.