Campus News

Preserving the legacy of Watsonville’s first Filipino immigrants

In partnership with the university, the community-led Tobera Project will develop an oral history archive and digital exhibition to be housed at McHenry Library.

UC Santa Cruz faculty and student researchers from the Humanities, Social Sciences, and Arts divisions are partnering with leaders of Watsonville’s Filipino community to document and preserve the rich history of the Manong Generation, the first wave of Filipino immigrants who came to California’s Central Coast in the 1920s and 1930s.

The Manong Generation were mostly young, single men who left the Philippines looking for work. In Santa Cruz County, they were recruited into low-wage farm jobs in the Pajaro Valley. They picked strawberries, cucumbers, and tomatoes and sorted beans. They put in 11-hour days hauling irrigation pipes through muddy fields. Though they were paid less than both white and Mexican workers at the time, they still often found a way to send a portion of their wages back to relatives across the Pacific.

At the time, women and children were often legally barred from making the journey over from the Philippines because labor recruiters only wanted single men, and racist policies in California also made it largely illegal for Filipino men to marry white women. As a result, there were only about a dozen families with children among the original Manong Generation in the Watsonville area. Most of those children are now in their 60s, 70s, and 80s. These days, they are community elders: the last remaining keepers of Manong Generation stories that have otherwise been erased from local history.

Watsonville-raised Dioscoro “Roy” Recio’s parents were both descendants of the local Manong Generation. His father, Dioscoro R. Recio, died in 2003, and when his mother also passed away in 2018, Recio began to fear that the stories of the area’s earliest Filipino immigrants could be lost forever. So he hatched a plan to preserve these memories for future generations.

“We have a term called ‘utang na loob,’ which is kind of like a debt of gratitude, or your responsibility to your ancestors and showing respect and appreciation for what they endured,” Recio said. “I wanted to make sure that their stories are honored, because when you look at history books, they’re not really recognized as part of the fabric of American society. This is our community, so it’s our responsibility to tell these stories.”

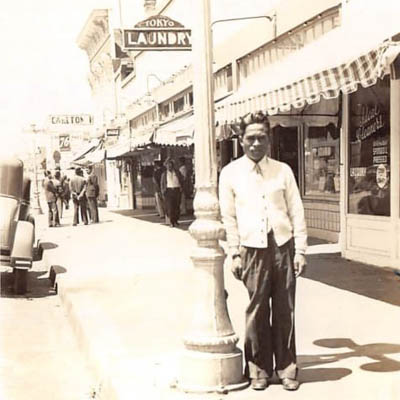

Recio kicked off his efforts with a special event in October of 2019 at the Freedom branch of the Watsonville Public Library. He invited members of the local Filipino community to bring photographs, documents, and artifacts related to their family histories for inclusion in an exhibit at the library called “Watsonville is in the Heart.”

Steven McKay, a UC Santa Cruz associate professor of sociology who studies Filipino labor and migration, stopped by to check out the event and connected with Recio, who shared his vision for a large public archive of Filipino history housed somewhere locally. Those conversations grew into a partnership with the university that was officially announced in April.

Now, a group of UC Santa Cruz researchers supported by The Humanities Institute are helping Recio bring his vision to life through developing an extensive oral history archive, digitizing and expanding the “Watsonville is in the Heart” exhibit collection, and planning a K-12 ethnic studies curriculum related to the project. The oral history archive and digital exhibition will eventually join the special collections at the university’s McHenry Library, where they’ll be accessible to both the local community and scholars and researchers around the world.

The team’s goal is to document the contributions of the Manong Generation while also shedding new light on the constant threats they faced from racial violence. Recio named the initiative The Tobera Project, in honor of Fermin Tobera, a Filipino American who was murdered during the infamous Watsonville Riots of 1930, when a white mob terrorized the local Filipino community for five days. Tobera was killed when a rioter shot into the side of a bunkhouse where he and other Filipino workers were hiding to protect themselves from the violence.

“These events became an important part of Asian American history and the long legacy of anti-Asian violence and imperialism,” said Associate Professor Steve McKay. “But the documentation pretty much lives on in just two local newspaper accounts, so it’s a very thin documentation. Now, we have the families that descended from the folks who actually experienced it, and for the first time we’re hearing their perspective.”

McKay and Assistant Professor of History Kathleen Gutierrez will lead UCSC’s work on The Tobera Project with Ph.D. candidates Meleia Simon-Reynolds and Christina Ayson-Plank. Undergraduates Nick Nasser and Toby Baylon will assist with conducting oral history interviews, alongside several trained community volunteers. Gutierrez said she believes the oral history archive will help to build greater understanding of the Manong Generation, including and beyond their experiences of the Watsonville Riots.

“We’re hoping that this archive is going to be much more expansive in showing the diversity of experience in everyday life for Filipinos in Watsonville, including their resilience and the struggles of belonging and othering that were present in the city from the riots onward,” she said. “This is a community-generated effort to allow for more vibrancy to these stories, and I think the community deserves to have that kind of dynamism shown in an archive.”

Among those who will contribute stories to the oral history archive is Frank Madolora, a UC Santa Cruz graduate and retired social worker in Santa Cruz County who helped to care for many members of the Manong Generation as they aged, including his father.

“One of the biggest regrets I have is that I didn’t talk with my father enough before he passed away because I know he had so many stories,” Madolora said. “This project is a way for me to remember him and to let others know about that generation of Filipinos. In our dialect, ‘manong’ means brother. They all came here as single males, then they bonded with each other and became each other’s families.”

For Recio, that sense of family and legacy are an important part of what he’s hoping to preserve through The Tobero Project. He chose to work with UC Santa Cruz, in part, to keep the project local and easily accessible for future generations. And already, young people are learning from and connecting with the project.

One example is UC Santa Cruz Ph.D. candidate Meleia Simon-Reynolds, who is mixed Filipino. She said she never learned much about the local Filipino American community while she was growing up in Santa Cruz County. But now, she’s designing educational resources for The Tobera Project so that local teachers will be better prepared to share this history with students in the future.

Ultimately, Recio says he hopes The Tobera Project will lift up and validate the voices of local Filipino communities, a mission that feels all the more important in light of recent waves of anti-Asian violence both locally and across the country.

“My father and his generation had to endure all of this racist sentiment just to survive,” he said. “At the time when Fermin Tobera was killed, he was just someone who was around who they thought didn’t belong. But The Tobera Project is saying, ‘Hey, we belong here, whether you like it or not.’ And we want to make sure that our ancestors’ stories are recognized as true American stories, just like anyone else’s.”