Campus News

Ultrasensitive antigen test detects SARS-CoV-2 and influenza viruses

Novel chip-based diagnostic technology can detect individual viral antigens in nasal swab samples to identify the viruses that cause COVID-19 and flu with a single test.

Researchers at UC Santa Cruz have developed a novel chip-based antigen test that can provide ultrasensitive detection of SARS-CoV-2 and influenza A, the viruses that cause COVID-19 and flu, respectively.

The test is sensitive enough to detect and identify individual viral antigens one by one in nasal swab samples. This ultrasensitive technique could eventually be developed as a molecular diagnostic tool for point-of-care use. The researchers reported their findings in a paper published May 4 in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“This is a chip-based biosensor capable of detecting individual proteins one at a time, and we show how it can be used to detect and identify the antigens for multiple diseases at the same time,” said senior author Holger Schmidt, professor of electrical and computer engineering at UC Santa Cruz.

“It’s a whole new way of looking for molecular biomarkers, not only for infectious diseases, but for any protein biomarkers used in medical testing,” added Schmidt, who holds the Kapany Chair in Optoelectronics and directs the W. M. Keck Center for Nanoscale Optofluidics at UCSC’s Baskin School of Engineering.

The current gold standard for diagnosing SARS-CoV-2 infections uses PCR technology to amplify small amounts of the virus’s genomic material, and samples are analyzed in centralized laboratories such as UCSC’s Colligan Clinical Diagnostic Laboratory. Antigen tests, which detect viral proteins, are faster and easier to use and have been approved for testing at the point of care (e.g., doctor’s offices) and even for at-home use, but these tests are not considered accurate enough for clinical decision-making, and their results may require confirmation with a more reliable technique.

The new chip-based antigen test is not only highly sensitive, but also enables simultaneous testing for multiple viruses from one sample. This is important for diseases such as COVID-19 and flu which have similar symptoms. Measures implemented to control the COVID-19 pandemic have reduced the incidence of flu dramatically, but in the future doctors may need a rapid test that can tell them which respiratory virus a patient is infected with.

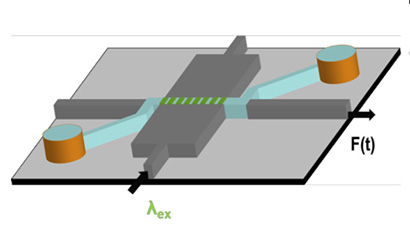

Schmidt’s lab, in collaboration with coauthor Aaron Hawkins’ group at Brigham Young University, has pioneered “optofluidic chip” technology for biomedical diagnostics, combining microfluidics (tiny channels for handling liquid samples on a chip) with integrated optics for optical analysis of single molecules.

To develop the new antigen test, Schmidt’s team designed a fluorescent probe bright enough that individual markers can be detected optically on the chip. “The ability to detect individual markers means there is no need for an amplification step, which removes some of the complexity of the processing,” he explained.

Schmidt’s lab had been developing tests for other infectious diseases when COVID-19 emerged as a global pandemic last year. At first, research ground to a halt as a statewide shutdown kept everyone at home. But it was clear to Schmidt that the diagnostic technology his lab was developing for Zika virus and other infectious diseases could be adapted for COVID-19.

“Once we were allowed to come back to the lab for essential research, my students started coming in to work in the lab by themselves on a coronavirus test,” Schmidt said. “It was a heroic effort by my students to develop these tests from scratch. First we were shut down by the pandemic, and then the wildfires hit and we had to evacuate our samples to Stanford and shut down again. But they kept going.”

Graduate student Alexandra Stambaugh led the effort and is first author of the paper. The team worked with the campus diagnostic lab to obtain nasal swab samples for testing. They only used samples that had tested negative for the coronavirus, adding viral antigens to the samples at clinically relevant concentrations to validate the tests.

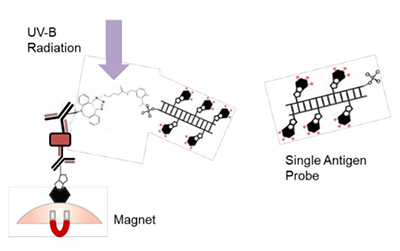

The test uses an “antibody sandwich” approach commonly used for immunoassays. In this case, antibodies specific for the target antigen are attached to magnetic microbeads, so that any target antigen present in the sample sticks to the beads. After washing, a second antibody with the fluorescent marker attached is added, and it binds to any target antigen present on the beads. The fluorescent markers are attached to the antibodies by a spacer that can be cleaved by ultraviolet light, which releases the markers to flow through the detection chip where they are detected one by one. The researchers attached a green marker to the coronavirus antibody and a red marker to the influenza antibody to distinguish between the two viruses.

In addition to Schmidt and Stambaugh, the coauthors of the paper include Joshua Parks , who initiated the development of the novel fluorescent markers, and Gopikrishnan Meena, both at UC Santa Cruz, as well as Matthew Stott and Aaron Hawkins at Brigham Young University. This work was funded by the National Institutes of Health and the University of California.