Campus News

Influential evolutionary biologist Barry Sinervo dies at age 60

Sinervo made landmark contributions ranging from evolutionary biology and game theory to the effects of climate change on animals and ecosystems.

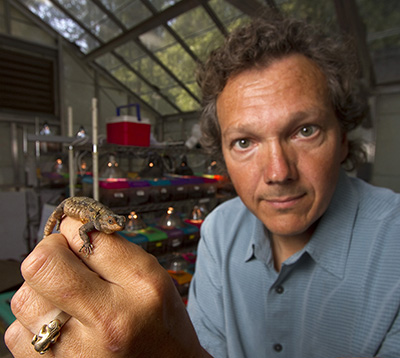

UCSC scientist Barry Sinervo

Barry Sinervo, a professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at UC Santa Cruz known for groundbreaking research in evolutionary biology and on the impacts of climate change, died on Monday, March 15, in Santa Cruz. Sinervo had been battling cancer for six years, but remained active in teaching and research. He was 60.

“The premature loss of Barry Sinervo’s blazingly creative thinking is a blow for the campus and for evolutionary biology and conservation science,” said Paul Koch, dean of UCSC’s Division of Physical and Biological Sciences.

Sinervo’s research in evolutionary biology spanned population genetics, game theory, behavior, and physiology. His decades-long research on social systems and mating behavior in lizards led to a series of influential publications on the evolutionary dynamics and behavioral ecology of their mating strategies.

Sinervo also led an international team of biologists in a survey of lizard populations worldwide that found an alarming pattern of population extinctions connected to climate change. Those findings, published in Science in 2010, led Sinervo to focus increasingly on the issue of climate change. He led collaborative research projects with a global network of scientists studying the impacts of climate change worldwide and worked to inform the public about the urgency of the growing climate catastrophe.

In 2014, Sinervo helped establish the UC-wide Institute for the Study of Ecological and Evolutionary Climate Impacts (ISEECI) and served as its director, leveraging UC’s Natural Reserve System to study how climate change will affect California ecosystems.

“He really connected UCSC globally with researchers studying the impacts of climate change around the world, and he was an important mentor for many scientists in developing countries,” said Bruce Lyon, professor of ecology and evolutionary biology. “There’s been an outpouring of sympathy from around the world, and also celebration of his life and achievements. It’s clear that Barry had a big impact on a lot of people.”

Sinervo was born in Port Arthur in Ontario, Canada. He earned his B.Sc. in biology and mathematics at Dalhousie University in Nova Scotia and his Ph.D. in zoology at the University of Washington in Seattle. He was an assistant professor of biology at Indiana University before joining the faculty at UC Santa Cruz in 1997.

For over three decades, Sinervo studied mating behavior in California’s side-blotched lizards. His research showed, among other things, that three different throat colors in male lizards correspond with different behaviors and mating strategies. The competition between these strategies (aggression, cooperation, and deception) takes the form of a rock-paper-scissors game in which no single type can dominate the population, and the abundance of each rises and falls in cycles.

Sinervo and his collaborators later discovered the same dynamic in an unrelated lizard species in Europe. More recently, he investigated how this type of mating system can be generalized and applied to other species, including mammals.

Sinervo’s research on the rock-paper-scissors game, starting with a landmark paper published in Nature in 1996, was influential in many areas beyond evolutionary biology and behavioral ecology.

“Even economists reference Barry’s lizards in their books on game theory,” said Daniel Friedman, professor emeritus of economics at UCSC. “Rock-paper-scissors is an iconic game for game theorists, and Barry was the first to show an animal species plays this interesting game in its social system.”

Friedman and Sinervo collaborated on several papers, taught courses together on evolutionary game theory, and coauthored a book, Evolutionary Games in Natural, Social, and Virtual Worlds (2016, Oxford University Press).

“He was a fun guy, alive with a new idea every minute. They didn’t all work, but they were always fun to explore, and many were really good ideas that no one else would have thought of,” Friedman said. “He was fearless and had his own way of looking at things. He reminded me of some of the early faculty, the type of people who made UCSC what it is.”

Sinervo’s longtime collaborator Donald Miles, professor of biological sciences at Ohio University, said Sinervo’s integrative perspective enabled him to see connections that broadened the impact of his work.

“Where other people would see bits of the puzzle, Barry would see the whole picture,” Miles said. “He’s arguably one of the major contributors to our understanding of evolutionary processes and of species responses to climate change. He had a big impact not only with his publications but also through his teaching and the training workshops he organized in countries all over the world—he touched so many people.”

Despite his ongoing health challenges, Sinervo’s passing took many of his colleagues by surprise. “It’s a shock that he isn’t with us now,” Friedman said. “I was amazed how he was able to keep going—he was just having too much fun.”

Lyon, who has been co-teaching a behavioral ecology field course with Sinervo for two decades, including the current quarter, said Sinervo was eager to continue working with students.

“All of us were kind of in awe of his spirit and how he handled everything that happened to him with such grace. He never lost his infectious enthusiasm for science and natural history,” Lyon said.

In the past year, while continuing to teach and maintain ongoing research collaborations, Sinervo was also devoting much of his time to completing a digital textbook on animal behavior. When his voice gave out, his wife stepped in to narrate the lecture videos. The book, Behavioral Genetics to Evolution, was published in January by Top Hat Marketplace.

Sinervo is survived by his wife of 35 years Jeanie Vogelzang, son Ari Sinervo, sisters Kristiina Alariaq and Sirppa Sterling, and brothers Pekka Sinervo and Ken Sinervo. Donations in his memory may be made to 350.org.