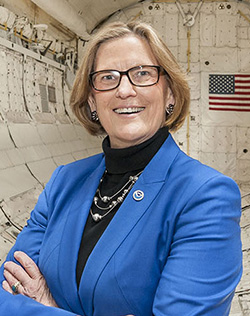

UC Santa Cruz Professor Emerita of Astronomy and Astrophysics Sandra Faber, and astronaut and oceanographer Kathryn Sullivan (Cowell ’73, Earth sciences) met for a good-humored, informal, and revelatory “fireside chat” this week.

The event was a high-profile way to publicize the naming of two interactive, high-tech floors in the newly renovated Science & Engineering Library in their honor: the Sandra M. Faber Floor (third floor) and the Kathryn D. Sullivan Floor (first floor), thanks to naming gifts from the Helen and Will Webster Foundation.

During their far-ranging discussion, Faber talked about the ins and outs of repairing the Hubble telescope, and Sullivan discussed the fine art of space walking and descending to the ocean’s deepest depths; she’s the first woman to reach the Challenger Deep, a spot seven miles beneath the ocean’s surface. She's also the owner of three Guinness World Records titles, including one for being the first person to visit both outer space and the deepest point on Earth.

But most importantly, the talk, moderated by Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Professor Beth Shapiro, offered endless inspiration for women in the audience who are pursuing STEM careers.

“There's no job that a woman has not done in the astronaut corps now from Space Station command to Space Shuttle command,” noted Sullivan, who noted that astronaut Peggy Whitson spent an astonishing 665 days in outer space, holding the U.S. duration record for time in orbit.

A library for the future

The Websters—major UC Santa Cruz donors—had a particular vision for this most recent gift.

“It was the Websters’ wish to name the library floors in honor of these women who broke glass ceilings before the term ‘glass ceiling’ even became popular,” said University Librarian Elizabeth Cowell during the fireside chat. “Our amazing honorees and speakers Sandra Faber and Kathryn Sullivan forged an incredible path in male-dominated professions years ago.”

This project is part of a renovated Science & Engineering Library that hosts advising, tutoring, and student support services in a place where students already gather, making it easier to find mentorship and take advantage of student success resources alongside library services, in addition to state-of-the art technology, Cowell said.

Two separate celebrations of these honors will be held in person after COVID-19 restrictions have been lifted.

The Sandra M. Faber Floor floor renovation project was finished early in the winter quarter of last year. The project expanded seating capacity to 440 in a mix of individual and group study spaces, and improved access to power and the wireless network.

Students were using and enjoying this interactive space for a brief period before the COVID-19 pandemic hit. The floor includes a large “laptop bar” with lavish backdrops featuring detailed photographs of space. The Kathryn D. Sullivan Floor will have an oceanographic theme. The centerpiece of the floor will be the Digital Scholarship Innovation Studio (DSI), where students will have access to a broad array of 3D creation tools and expert assistance.

The library will also expand its physical collections capacity by about 30% by installing new compact shelving similar to what has been in McHenry Library since 2008. The project is currently under development, and is expected to be ready for use by this upcoming winter quarter.

Highs and lows

The talk was a rare opportunity for audience members to ask these distinguished speakers questions about their long careers. One of the Zoom attendants got right to the point: How would Sullivan compare and contrast space walking to exploring the ocean’s deepest depths?

Sullivan became the first woman in the United States to walk in space in 1984. In 2020, she became the first woman to reach the deepest point in the ocean.

Sullivan said that those adventures had just one thing in common: “You can't be in either of those environments without a very well engineered craft that gives you the kinds of conditions we need (for human survival). The marvels of engineering are essential to both of them.”

“But the big differences are stark right away,” Sullivan continued. “When you go into space you've gone from the atmospheric pressure that we're all sitting in here now to zero. Outside the little sphere that you’re sitting in, you’re riding a bomb to get into orbit, so it’s just as explosive and intense as that phrase would suggest.”

In contrast, “a submersible into the deep sea is a very serene four-hour elevator to the bottom,” Sullivan remarked. “From orbit, you can see about 100 miles from the spacecraft window. In the deep sea you can only see as far as the lights that you brought with you will allow, which is usually about 30 feet. And you see critters all the way down. In space, the only critters are the ones that are with you in the spacecraft when you go into orbit.”

Busting down the door

Shapiro asked both scientists about their experiences with sexism.

“Actually, I certainly have encountered issues over gender,” Faber said. “But I have an irrepressible desire to speak up all the time. As a result, I’m not [sheepish] about coming forward. I just speak up, and people have paid attention, for which I'm very grateful.”

Faber recalled the glaring sexism she experienced as a graduate student at the Palomar Observatory in San Diego County and at Mt. Wilson Observatory in Los Angeles. At Palomar, she was barred from an area that was informally called the Monastery, sending a "no women allowed” message. “I couldn’t stay in the Monastery for obvious reasons so I slept on the gatekeeper’s sofa.”

But when she became the first female staff member at Lick Observatory in the '70s, her experience was much different.

“First of all, the big barrier that I faced by virtue of gender was that I got pregnant right away,” Faber said. “And so I had to deal with being an assistant professor and a pregnancy at the same time.”

But Faber said the reaction of Lick Observatory Director Robert P. Kraft was “incredibly wonderful. He said, ‘We don’t have any policies, so therefore, what I’m telling you is, take as much time as you need, and we will ask no questions whatsoever.'”

Sullivan said she’d led “a blessed life” in terms of not having to deal with gender-based barriers.

“Earlier pioneers went before me," said Sullivan. "The doors to some of the fields I was going into—I wouldn’t say they were wide open, but they weren’t nailed shut, either.

Instead, Sullivan spoke of relatively minor irritations, such as getting some pushback from men on research ships where the men had grown used to “doing whatever they want, whatever that might be—you know, tell raunchy jokes, burp, or hang around in their underwear—be little boys again, and now there’s going to be a woman here to make them feel more self-conscious about that.”

Unforeseen challenges

Audience members wanted to know about the biggest challenges that Sullivan and Faber had faced in their careers. Both of them have had to deal with complex problem-solving in high-pressure situations. Faber mentioned her essential—and highly stressful—work contributing to the optical design of the Keck Telescopes and leading the construction of the multi-object DEIMOS spectrograph for the Keck. Faber and Jon Holtzman also played a major role in diagnosing Hubble's optical flaw and executing the subsequent repair.

Supervising the spectrograph construction and diagnosing some early technical problems was “the hardest thing I ever did” because of the huge learning curve, she said.

“I had never built an instrument before; I knew very little about optics," Faber said. "I knew nothing about mechanical design or anything like that, and I was the head of this team … I take my hat off to the brave souls among our astronomy folk who devote their entire lives to making instruments that the rest of us observe with—I did it once and it almost killed me.”

Faber has taken on and surmounted many other formidable challenges in her career. She is one of the leaders worldwide in the study of galaxies, with an enduring legacy of contributions across a wide range of topics in galaxy structure, galaxy evolution, and cosmology.

Assessing risks

Asked about her own personal challenges, Sullivan went into detail about the risks she took by going into space. Sullivan rode on the Space Shuttle Challenger in 1984, the 13th flight of NASA's Space Shuttle program and the sixth trip for the Challenger, two years before seven astronauts died when the Challenger blew apart 73 seconds after liftoff from Cape Canaveral, Florida. Sullivan knew four of the crew members, so the tragedy hit home.

In shuttle missions, “there is an irreducible risk that is never going to be zero,” Sullivan said, regarding the tragic accident. “If anything, that confirmed that for me.”

Regarding the undeniable risk of going into space, Sullivan said, “it's human beings doing things no humans have done before, so they will make errors of omission and commission. And I weighed that out and decided this makes sense to me not for fame and not for fortune, but in terms of the potential value to humankind and the value to my country, and the opportunity to serve my country. That was the value.”

Future plans

Both of these science pioneers have nothing left to prove. But Faber and Sullivan still have dreams and grand ambitions for the future.

Sulivan would love one more ride in space, if such a thing could be arranged. “And if the moon happened to be involved," she said, "I wouldn’t object.”

Faber dreams of having an Earth Futures Institute at UC Santa Cruz. The project—involving a collaboration with UC Riverside—is currently in the conceptual phase.

This new entity is designed to focus world attention on “the existential question of Earth’s future on the time scale of decades to a million years,” according to the project’s website. Funding is a serious challenge, “but if I could wave a magic wand and have a wish, we would have an Earth Futures Institute at UC Santa Cruz, and we would be addressing the most important questions in the history of the human race,” said Faber.

In the meantime, Faber is celebrating the renovated floors that have been named in her and Sullivan’s honor. “I am so pleased that my name is going to be associated with a part of this beautiful building,” she said. “The floor has been decorated and graced with many wonderful astronomical images, and you can look out at the redwoods. It’s food for the soul.”