Campus News

UC Santa Cruz leads interdisciplinary consortium for astrobiology research

With funding from NASA, the UCSC-led team will lay the foundation for detecting the signatures of life in the atmospheres of other planets.

The NASA Astrobiology Program has awarded a five-year, $5 million grant to an interdisciplinary consortium led by the University of California, Santa Cruz, to trace the volatile elements that form the atmospheres of planets, establishing a scientific foundation for detecting the signatures of life on other worlds.

Natalie Batalha, professor of astronomy and astrophysics at UC Santa Cruz, will lead the consortium, one of eight new research teams selected by NASA to inaugurate its Interdisciplinary Consortia for Astrobiology Research (ICAR) program. In addition to UCSC, the consortium includes researchers at the University of Hawaii at Manoa, University of Colorado, Boulder, University of Kansas, and NASA Ames Research Center.

“We want to understand the physical processes that impact planetary atmospheres,” Batalha said. “We must understand those physical processes and their effects in the absence of life so that we will be able to recognize the signs of life when we see them.”

Batalha served as the project scientist for NASA’s highly successful Kepler Mission, which discovered more than 2,500 exoplanets. A recent analysis of Kepler data suggests there are at least 300 million potentially habitable worlds in our galaxy. Batalha noted, however, that a planet in the “habitable zone” of its star (where liquid water could pool on the planet’s surface) is not guaranteed to be a truly habitable environment.

“One of the takeaways from the Kepler Mission is that the diversity of exoplanets in the galaxy far exceeds the diversity of our own solar system,” she said. “If we want to understand the diversity of rocky, habitable zone planets, we have to study the physical processes that sculpt the atmospheres of all planets—even those not amenable to life as we know it.”

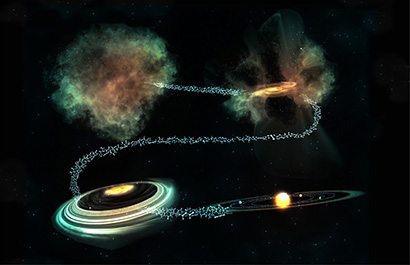

For Batalha’s team, that means “following the volatiles,” tracing the path of the volatile elements like carbon and oxygen that make up a planet’s atmosphere. That path goes from star-forming clouds into protoplanetary disks, to the building blocks of planets, and eventually into planets themselves, where volatile elements can move between the surface, atmosphere, and interior, and even be lost to space.

The launch of the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) in 2021 will usher in a new era of exoplanet exploration and the characterization of exoplanet atmospheres. The consortium will develop the tools needed to interpret observations of exoplanet atmospheres made by JWST and the latest generation of ground-based telescopes.

The researchers will address four fundamental science questions: What is the inventory of volatiles in planetary building blocks? What are a planet’s external sources and sinks of volatiles (in other words, where do they come from and where do they go)? How are volatiles distributed between a planet’s interior, surface, and atmosphere? And what can atmospheric observations tell us about the volatile inventories and chemistries of exoplanets?

Researchers at the University of Hawaii led by Eric Gaidos will investigate the formation of planets and their volatile content using astronomical observations of protoplanetary disks and young planets, laboratory experiments that simulate conditions in the interiors of planetesimals and growing planets, and analysis of meteorites and samples returned from asteroids.

Meredith MacGregor at the University of Colorado, Boulder, will lead analysis of circumstellar disk observations using the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) combined with other ground-based observatories. She will also coordinate multi-wavelength observing campaigns to explore the properties of and mechanisms behind stellar flaring in order to better understand how these events can damage planetary atmospheres over time.

Ian Crossfield at the University of Kansas will lead isotopic abundance analyses of exoplanets, brown dwarfs, and dwarf stars. He will also consult and assist with the planning and analysis of Hubble Space Telescope and JWST spectroscopy of nearby exoplanets. Thomas Greene is leading the effort at NASA Ames Research Center to provide guaranteed-time JWST observations of exoplanet atmospheres and model their chemical abundances, clouds, and photochemical effects.

“Our team has a broad range of expertise and unparalleled access to the telescopes and facilities needed to carry out this research and meet the challenge of not just finding life on other worlds, but having confidence that we can identify signatures of life when we see them,” Batalha said.

At UC Santa Cruz, the team includes faculty in two departments, Astronomy & Astrophysics and Earth & Planetary Sciences (EPS). Jonathan Fortney, professor of astronomy and astrophysics and director of the Other Worlds Laboratory, will conduct theoretical and modeling work on exoplanet structure and atmospheres; Ruth Murray-Clay, the Gunderson Professor of Theoretical Astrophysics, will conduct a wide array of theoretical work, including the physics of disk structure and evolution and the processes of atmospheric mass loss.

Francis Nimmo, professor of EPS, will model planetesimal volatile acquisition and retention; Myriam Telus, assistant professor of EPS, will study meteorite outgassing and cosmochemistry; and Xi Zhang, assistant professor of EPS, will model exoplanet atmospheres and help interpret exoplanet spectra in the context of cloud physics. Andrew Skemer, associate professor of astronomy and astrophysics, and Rebecca Jensen-Clem, assistant professor of astronomy and astrophysics, will also contribute to the consortium.

Batalha, who leads UCSC’s interdisciplinary Astrobiology Initiative, said the NASA ICAR award is a testament to the strength of UCSC’s faculty in this area of research.

“I came to UC Santa Cruz knowing that the pieces were in place already for a strong astrobiology program. This funding allows us build on that foundation and means that astrobiology at UCSC can flourish,” she said.

The UCSC Office of Research provided seed funding for the Astrobiology Initiative.