Campus News

Powerful new AI technique detects and classifies galaxies in astronomy image data

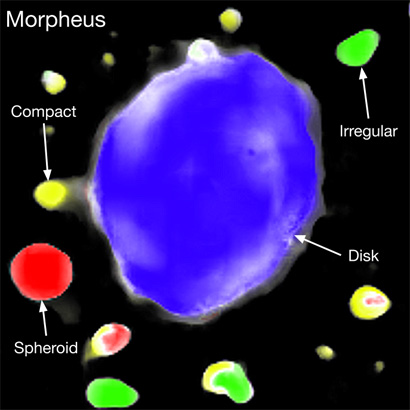

UCSC researchers developed a deep-learning framework called Morpheus to perform pixel-level morphological classifications of objects in astronomical images.

Researchers at UC Santa Cruz have developed a powerful new computer program called Morpheus that can analyze astronomical image data pixel by pixel to identify and classify all of the galaxies and stars in large data sets from astronomy surveys.

Morpheus is a deep-learning framework that incorporates a variety of artificial intelligence technologies developed for applications such as image and speech recognition. Brant Robertson, a professor of astronomy and astrophysics who leads the Computational Astrophysics Research Group at UC Santa Cruz, said the rapidly increasing size of astronomy data sets has made it essential to automate some of the tasks traditionally done by astronomers.

“There are some things we simply cannot do as humans, so we have to find ways to use computers to deal with the huge amount of data that will be coming in over the next few years from large astronomical survey projects,” he said.

Robertson worked with Ryan Hausen, a computer science graduate student in UCSC’s Baskin School of Engineering, who developed and tested Morpheus over the past two years. With the publication of their results May 12 in the Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series, Hausen and Robertson are also releasing the Morpheus code publicly and providing online demonstrations.

The morphologies of galaxies, from rotating disk galaxies like our own Milky Way to amorphous elliptical and spheroidal galaxies, can tell astronomers about how galaxies form and evolve over time. Large-scale surveys, such as the Legacy Survey of Space and Time (LSST) to be conducted at the Vera Rubin Observatory now under construction in Chile, will generate huge amounts of image data, and Robertson has been involved in planning how to use that data to understand the formation and evolution of galaxies. LSST will take more than 800 panoramic images each night with a 3.2-billion-pixel camera, recording the entire visible sky twice each week.

“Imagine if you went to astronomers and asked them to classify billions of objects—how could they possibly do that? Now we’ll be able to automatically classify those objects and use that information to learn about galaxy evolution,” Robertson said.

Other astronomers have used deep-learning technology to classify galaxies, but previous efforts have typically involved adapting existing image recognition algorithms, and researchers have fed the algorithms curated images of galaxies to be classified. Hausen built Morpheus from the ground up specifically for astronomical image data, and the model uses as input the original image data in the standard digital file format used by astronomers.

Pixel-level classification is another important advantage of Morpheus, Robertson said. “With other models, you have to know something is there and feed the model an image, and it classifies the entire galaxy at once,” he said. “Morpheus discovers the galaxies for you, and does it pixel by pixel, so it can handle very complicated images, where you might have a spheroidal right next to a disk. For a disk with a central bulge, it classifies the bulge separately. So it’s very powerful.”

To train the deep-learning algorithm, the researchers used information from a 2015 study in which dozens of astronomers classified about 10,000 galaxies in Hubble Space Telescope images from the CANDELS survey. They then applied Morpheus to image data from the Hubble Legacy Fields, which combines observations taken by several Hubble deep-field surveys.

When Morpheus processes an image of an area of the sky, it generates a new set of images of that part of the sky in which all objects are color-coded based on their morphology, separating astronomical objects from the background and identifying point sources (stars) and different types of galaxies. The output includes a confidence level for each classification. Running on UCSC’s lux supercomputer, the program rapidly generates a pixel-by-pixel analysis for the entire data set.

“Morpheus provides detection and morphological classification of astronomical objects at a level of granularity that doesn’t currently exist,” Hausen said.

An interactive visualization of the Morpheus model results for GOODS South, a deep-field survey that imaged millions of galaxies, has been publicly released. This work was supported by NASA and the National Science Foundation.