In 1977, two spacecraft—Voyager 1 and 2—were launched into space carrying a pair of round metal plaques filled with information designed to acquaint any extraterrestrial who happened to find them with Earth and its inhabitants.

Included on the covers of both those “Golden Records” was a starburst-shaped map, co-created by UC Santa Cruz Emeritus Professor of Astronomy and Astrophysics Frank Drake. It used pulsars—rapidly spinning remains of dying stars that emit narrow beams of light—to help other intelligent life forms understand where our small orb is located.

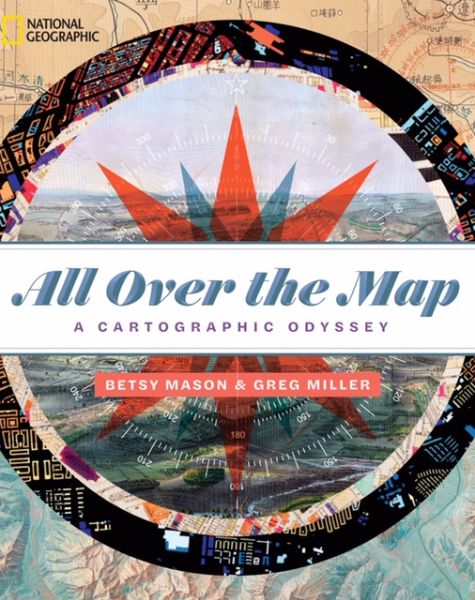

That clever roadmap to Earth is just one of the more than 200 maps included in a book created by two graduates of the campus’s Science Communication Program, Betsy Mason and Greg Miller. Titled All Over The Map: A Cartographic Odyssey, it was published in 2018 by National Geographic.

The 320-page illustrated tome includes things like disturbingly accurate Russian spy maps; a diagram showing where to find booze during Prohibition in New York City; a chart of fracking wells in Williston, North Dakota; and a map showing the location of dozens of ships that were abandoned during California’s Gold Rush and still lie buried beneath San Francisco’s financial district. There is even a map of Westeros from HBO’s Game of Thrones.

“I’ve always been intuitively drawn to maps because they are visually compelling,” said Miller, a former Stanford neuroscientist and current freelance journalist who lives in Portland, Ore. “Now (after doing research for the book and for a blog the pair created) I realize every good map also has a story to tell.”

And tell, the duo did.

Drawing out stories

Mason and Miller met at UC Santa Cruz’s graduate Science Communication Program, then headed by John Wilkes. Each was coming off a career crisis. Mason, a Stanford-trained geologist, was working in the oil industry in Texas, and Miller had come to realize that spending all day in a lab was not his idea of happiness. Both were drawn to science journalism and UC Santa Cruz.

Eventually the pair landed jobs at Wired, where they pitched the idea of a blog about maps, which sent them on a hunt that would last seven years and eventually result in a book deal.

During that time, the two unearthed spy maps, political maps, and maps of ancient cities. Some were beautifully wrought, others crudely drawn. Many of the diagrams were from the David Rumsey Map Collection at Stanford Libraries, which contains more than 150,000 maps, but others were from government files, archives, and obscure scientific papers. As the pair discovered, each map carried a story, too: stories of explorers, of propagandists, of scientists and criminals, of zealots and the obsessed.

According to Mason, for instance, there was an adventurous museum director who, in the 1970s, couldn’t find a good map of the Grand Canyon for his and his wife’s visit. The man decided to make his own. Eight years and hundreds of thousands of dollars later, thanks to helicopter surveys and laser measurements, he had a stunningly detailed map of the chasm drawn by a special team of Swiss cartographers and published by National Geographic.

Then, there was the atlas that saved the lives of a bunch of 17th-century English buccaneers. Coming home after years spent marauding off the coasts of South and Latin America, the pirates faced a possible death sentence, Miller said. Instead, the men handed King Charles II a hand-drawn copy of a book of sailing charts and navigation information they’d looted from a Spanish galleon. King Charles was so happy to have the information that he spared their lives.

True map geek

“Even though I thought I was a map geek before I started the blog, I really had very little appreciation for how wonderful maps were,” said Mason, who is headquartered in the San Francisco Bay Area. “They are so much greater than I ever imagined. After seven years spent writing about maps, I love them more and more. Now, I think I qualify as a true map geek.”

She’s such a map geek, Mason even tracked down the graphic designer who created the beautiful, medieval-looking map of the kingdom of Westeros that the diabolical queen, Cersei Lannister, commissioned during a season-seven episode of Game of Thrones. After some negotiating, Mason managed to win permission to use the map in the book.

Miller, who may have had an even tougher assignment, got the OK to publish the schematic of the Death Star from the Star Wars movie franchise.

But ask the pair what’s the allure of maps to humans and they struggled to narrow down the reasons.

“I think anybody who says they don’t like maps just hasn’t met the right map,” Mason said finally.