While Alex Krohn was completing his Ph.D., he visited numerous UC Natural Reserves looking for reptiles and amphibians. With dozens of protected wildlands located in a wide variety of ecosystems across the state, the reserves in the UC Natural Reserve System (NRS) are popular places for scientists to collect specimens and do field research.

Trying to determine whether certain species of interest lived on a given reserve, however, wasn’t as easy as the UC Berkeley graduate student had hoped. Sometimes a reserve’s species list was incomplete, or in other cases was out of date and considerably older than he was.

Now, as assistant manager of the UC Santa Cruz campus reserve, Krohn is working to remedy that problem. In 2019, he launched a survey of the birds, plants, fish, fungi, insects, vascular plants, mammals, bryophytes (mosses and liverworts), and lichens at all of UC Santa Cruz’s Natural Reserves. In time, he wants this biological snapshot to include all 41 reserves now in the NRS.

Monitoring for change

“Our data will be used to study how the reserves’ diversity has changed over time. Where no such data exist, our data will serve as a crucial baseline to study future change,” Krohn said.

Krohn has designed the survey to train students in field biology while benefiting the ecological community. It will not only update knowledge about NRS reserves, but also expose students to field and museum work, while augmenting the collections of UC’s natural history museums.

“The survey adds value to the NRS’s library of ecosystems,” said Peggy Fiedler, executive director of the NRS. “Researchers want to know what species occur at which reserves and which times of year they can be found. The specimens and species lists will encourage more studies on NRS lands and improve our ability to protect California’s biodiversity.”

Krohn’s plan is to survey UCSC’s four NRS reserves first as a proof of concept. He hopes the results will inspire other campuses to conduct comprehensive inventories their own NRS reserves.

“We want to show, given relatively little funding and a short amount of time, how much new information we can gather for the reserves about the biodiversity they currently have,” he said. The first year of the survey cost less than $8,000. The funds have provided stipends for crew leaders and money for gas and collecting equipment.

The survey will focus on one reserve at a time over the course of an entire year. This enables surveyors to witness the full range of seasonal shifts such as migrations, flowering, births, and deaths.

Student surveyors

First up is Younger Lagoon Reserve. Extending across wetlands, coastal terrace, and a beach, the reserve boasts a wide variety of habitat types and species. It’s an easy site to visit as it’s located just a few miles from the main UC Santa Cruz campus.

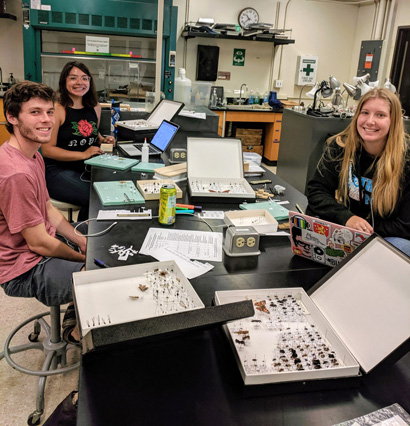

Teams of undergraduates have been sampling the reserve regularly since spring. Each team specializes in a particular type of organism, such as arthropods or plants, and is led by a local expert, graduate student, or knowledgeable undergraduate. The specimens each team collects are deposited at UC Santa Cruz’s Norris Center for Natural History, where Krohn is assistant director.

Because the methods are straightforward to conduct and repeat, groups such as classes should be able to update the survey in the future. “As long as someone is there to help identify what you catch, pretty much anyone can do this survey,” Krohn said.

A chance to lead

Jessica Correa led the Younger Lagoon insect team last spring. An environmental studies and sociology major, Correa had spent her junior year surveying the insects of UC Santa Cruz’s campus grasslands for her capstone project. Krohn hired her to lead the insect team surveying Younger Lagoon Reserve in spring before she graduated.

“I’m usually just part of the team. I hadn’t been a leader. The survey gave me so much experience in how to manage a team and work with different people’s schedules,” Correa says.

Before heading out into the field, Correa helped train her team on how to survey for and collect any specimens they gathered. In the field, she planned how long the team was going to collect, mapped out where each member would trap, and wrangled the most complex traps herself. Back at the Norris Center, she organized sessions for team members to identify, pin, and label insects for the museum’s permanent collection.

Making connections in the field

The inventory uses tried-and-true sampling protocols at every turn. These include laying wooden boards on the ground to shelter small animals such salamanders and voles, and shining lights that draw insects after dark.

“It was like hiking with a purpose,” said Emma Brown, a junior environmental studies major at UC Santa Cruz. A member of the Younger Lagoon insect crew, Brown began collecting with Correa last spring and earned two units for her efforts. She is now a paid intern for the project.

The survey trips have opened Brown’s eyes to the connections between insects and their environments. She’s noticed certain species waxing and waning with the weather, observed which reserve soils scarab beetles preferred to breed in, and followed ant-eating wrens to locate the best spot for her ant traps.

Brown feels her participation in the survey is laying the groundwork for her future. “I plan to keep doing insect collecting and continue on to graduate school,” Brown said, “so I know these skills definitely will help me out then.”

A new view of museum collections

“This project connects experts here at the museum and the university with our undergraduates to get people involved in research,” Krohn said. “They can teach students how to collect and stain a lichen or dry a fungus.”

Information about each specimen is entered into the Norris Center’s databases, which feed into the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF), an online database of museum specimens and other biodiversity data from around the world. The information will also be available on ReserveMapper, a tool that displays specimens collected specifically from NRS reserves.

By doing the preservation and cataloging themselves, students “come away understanding how natural history museums are a library for life, and have a new appreciation for all they do outside of exhibits and displays visible to the public,” Krohn said.

It also eases the burdens of reserve managers. While most have years of training in the natural sciences, it’s virtually impossible for one person to possess the specialized knowledge required to differentiate similar-looking species from all taxa. For example, distinguishing certain species of moths requires dissecting their reproductive parts, while some lizards can only be told apart by counting their scales.

“We can take that work off the shoulders of reserve managers, who might not be experts in how to properly store plants or prepare museum specimens either,” Krohn explained.

Baseline data

The project comes not a moment too soon given the magnitude of human impacts on the natural world, Correa said. Not only are amphibians and large mammals in deep declines, but some entomologists fear a so-called “insect apocalypse” has left populations of arthropods at potentially catastrophic lows.

“It’s important to be studying it before the species decline,” Correa said.

The survey also afforded students a bonus: getting to experience wilder corners of nature. “We got to go into part of the reserve where most people are not allowed except to do research. We would find bird bones, small mammal skulls, and we tried to figure out what happened to them. You don’t get that on Natural Bridges Beach next door; the public is always there,” Correa said.

Krohn’s ambitions for the survey have been borne out by early results. After one quarter of surveying, students increased the number of lichens known from Younger by 430%, and insects by more than 1000%. The trend held true even among relatively well characterized groups; students found two new species of snake never before documented at the lagoon.

At Younger Lagoon, groups like birds and plants have been well documented. But other taxa at the reserve, like fungi and lichens, were not nearly as well known.

Younger Lagoon Reserve Director Elizabeth Howard said getting information about these other groups of organisms is going to be a huge bonus. “Once we have those resources, we’ll start to see research questions and projects on those taxa,” she said. And that will benefit individual researchers and encourage more people to expand our understanding of the natural world.