Campus News

Santa Cruz County faces significant gap in food security, study finds

As the season of holiday feasting approaches, a new study reveals that Santa Cruz County residents who are most at risk of food insecurity may be missing an average of five meals a week.

As the season of holiday feasting approaches, a new study reveals that Santa Cruz County residents who are most at risk of food insecurity may be missing an average of five meals a week.

The findings were issued in a report, Tracking the Meal Gap in Santa Cruz County: An Index of Food Insecurity, 2014-2018, that was released Nov. 13 at a gathering of nonprofit, government, and community stakeholders.

The report was produced by the UC Santa Cruz Blum Center on Poverty, Social Enterprise, and Participatory Governance and Second Harvest Food Bank Santa Cruz County.

Key findings include:

- In 2017-18, 43% of food assistance needs went unmet among households earning less than $50,000 annually, even after accounting for assistance provided by government and nonprofit sources, including CalFresh and food banks.

- Santa Cruz County households with annual earnings of less than $50,000 missed 21 million meals in 2017-18. If these missed meals were distributed equally among households in this income bracket, this would mean that each person missed approximately five meals per week, and was likely forced to seek less expensive, less nutritious options or go hungry.

- Food assistance would need to nearly double to meet the needs of households earning under $50,000.

The 2014-2018 Food Insecurity Index refers to the “meal gap” between the total number of meals needed by low-income households and the number of meals provided. People are considered food insecure if they have limited or uncertain access to nutritious, safe food. Common indicators include skipping meals, hunger, and cutting down on portions.

“This is the first time an index of this kind has been calculated in our county,” said Heather Bullock, a professor of psychology and the director of the Blum Center. “This report is our first step in mobilizing diverse stakeholders to work together on this issue.”

The report, which includes recommendations for reducing food insecurity, will be issued annually with an updated index. “We believe this will quickly become an invaluable community resource,” said Bullock.

Recommendations and collaboration

Increasing CalFresh enrollment reduces food insecurity, and the authors calculate that if all eligible residents enrolled, county residents would access an additional 5 million meals—reducing missing meals by about 20 percent.

“Reducing the stigma associated with food assistance programs is crucial,” said Bullock.

The report also noted a decline between 2014-2018 in the most vulnerable population, which the authors attribute to rising housing costs that are forcing out low-income households. The cost of living in Santa Cruz County contributes to the county having the second-highest effective poverty rate in the state, as well as the second-highest food insecurity rate, said Willy Elliott-McCrea, chief executive officer of Second Harvest Food Bank. Households making less than $50,000 annually may spend an average of 75% of their income on shelter, he said.

“The increase in shelter costs feeds the cycle of food insecurity and chronic disease,” he said. “We know that food insecurity can cause poor health and poor health in turn can deepen food insecurity.”

David Amaral, a doctoral candidate in politics at UC Santa Cruz, built the index in consultation with Michael Enos, who has provided similar training to other counties, by gathering data from governmental agencies, nongovernmental organizations, and nonprofits.

“This index is different from national indices, because we have specific information about food assistance provided by food banks and nonprofits and NGOs,” said Amaral. “Our goal was to establish the extent of food insecurity and how much it’s being met in this county.”

The Nov. 13 gathering marked the first time all the local food and nutrition providers gathered together to talk about how to address the cycle of food insecurity.

“It was gratifying that the research seemed to be directly and immediately useful to the people on the ground who are trying to address these problems,” said Amaral. “That doesn’t happen every day in academia.”

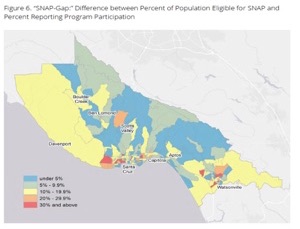

Attendees honed in on a map that identified three key areas where a high proportion of residents qualify for food assistance but aren’t enrolled. The biggest so-called “SNAP gaps” are in central Santa Cruz, Capitola, and Watsonville. “It was exciting to see people starting to forge a network, and to hear their eagerness to start developing strategies to address the problems that were showing up,” said Amaral.

“This collaboration, with university researchers teaming up with community partners, embodies the best of what we can do when we work together to address social problems,” said Katharyne Mitchell, dean of the Division of Social Sciences at UCSC. “I look forward to seeing the progress that comes from this partnership.”

Elliott-McCrea, whose food bank reaches more than 55,000 people each month, underscored the value of working together. “The more we can leverage and cross-promote and advocate for the full range of nutrition programs, the more effective we’ll all become,” said Elliott-McCrea.

Second Harvest, founded in 1972, was the first food bank in California and is the second-oldest in the nation. It distributes over 8 million pounds of food annually to 100 food pantries, schools, soup kitchens, group homes, and youth centers, as well as 100 Second Harvest sites. Among the other local organizations that contributed data for the report were Grey Bears, Community Bridges, and Valley Churches United Missions.