Campus News

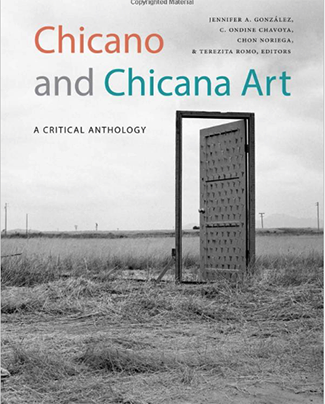

New anthology of essays about Chicana and Chicano art edited by arts professor Jennifer González

“Chicano and Chicana Art: A Critical Anthology” offers an overview of the history and theory of Chicano and Chicana art from the 1960s to the mid-2000s.

Designed to be an introductory teaching collection, the book is comprised of a diverse selection of thematically organized essays by leading scholars, tracing the development of Chicano/a art from its early role in the Chicano civil rights movement to its mainstream acceptance in American art institutions.

“This is the first edited anthology of scholarly writings about Chicana/o visual arts,” noted UC Santa Cruz history of art and visual culture professor Jennifer González. “Previously only art museum catalogs, single-author texts and monographs have been published.”

González served as chief editor for the 552-page book, just published in February by Duke University Press, in collaboration with co-editors Ondine Chavoya, Chon Noriega and Tere Romo.

“This is not intended to be a comprehensive collection, but rather to serve as a teaching tool for students and the general public,” González added. “The articles are carefully chosen for the way their ideas intersect around regionally specific analyses, conceptual themes, or critical debates. Each section has a brief introduction to orient the reader to these concerns. I will be teaching a course on Chicana/o art next quarter using the book for the first time.”

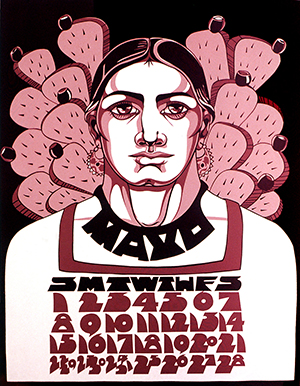

The essays in the book address a number of themes, including the politics of border life, public art practices such as posters and murals, and feminist and queer artists’ figurations of Chicano/a bodies.

They also cover the many cultural and artistic influences, ranging from American graffiti and Mexican pre-Columbian spirituality to pop art and modernism, that have informed Chicano/a art’s practice.

As González notes in the book’s introduction:

“We hope this anthology will draw the interest of students of Chicana/o history and culture, as well as art theorists and visual studies scholars who practice in a field that has, until relatively recently, generally ignored the contribution of Chicana/o art to American and contemporary art history.

“What does the future hold for globally mobile citizens, refugees, Indigenous populations, and noncitizens? Are the terms ‘Chicano’ and ‘Chicana’ irretrievably historical and dated, or will they be taken up again, in a new way? How will marginalized populations respond creatively to ongoing, systematic economic and racial injustice? These are important concerns of our present time; they have changed little in the past fifty years since the Chicano movement was launched. Developing a response to these questions nevertheless remains one of the goals toward which Chicana/o art is directed, and to which this collection hopes to contribute.”