Campus News

The ghosts of fascism

Madeleine Albright, the United States’ first female secretary of state, spoke about the rise of authoritarian governments and the enduring threat of fascism during her sold-out talk in front of 2,500 people in downtown Santa Cruz on Tuesday night.

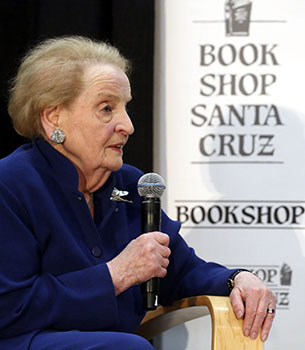

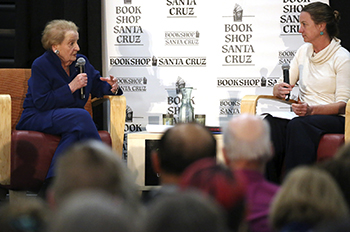

Former Secretary of State Madeleine Albright in conversation with Pulitzer Prize winning journalist Martha Mendoza at Kaiser Permanente Area in an event sponsored by Bookshop Santa Cruz. Albright is on a tour to promote her book, "Fascism: A Warning". Photo by Shmuel Thaler / Santa Cruz Sentinel

Madeleine Albright, the United States’ first female secretary of state, warned about the rise of authoritarian governments and the enduring threat of fascism during her sold-out talk in front of 2,500 people in downtown Santa Cruz on Tuesday night.

Albright recently topped the New York Times bestseller list with her 2018 book, Fascism: A Warning, in which she traces fascism’s roots, calls out the global rise of right-wing authoritarian regimes, and expresses grave concern about divisions, resentments, and isolationism in the United States.

During her on-stage discussion at the Kaiser Permanente Arena with Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter Martha Mendoza, (Kresge ’88, individual major, journalism and education) Albright drew from global as well as personal history to make the case that fascism remains a virulent threat. “The definition (of) fascist is someone who identifies with one group at the expense of another, thinks the press is the enemy of the people, believes various institutional structures don’t work, and is prepared to use violence to maintain power,’’ said Albright, who served as Secretary of State from 1997 to 2001 under President Bill Clinton.

Albright, addressing the largest crowd on her speaking tour, talked about the insidious, creeping quality of fascism, which can worm its way into a society and take over before the population has a chance to sound the alarm. At one point, Albright quoted Benito Mussolini, whom she described as the first fascist: “If you pluck a chicken one feather at a time, nobody notices.” Albright added that “there is a lot of feather-plucking going on right now.”

In her book, Albright never characterizes President Donald Trump as fascist, though she has described him as “the most anti-democratic leader that I have studied in American history.”

Even when Trump was not mentioned by name, he was a shadow looming over Albright’s discussion with Mendoza.

Albright, during a talk that briefly overlapped Trump’s State of the Union address, called upon audience members to become involved in local and national politics, while calling leaders out “for not respecting the judiciary,’’ encouraging people to revile the press, and acting as though they are “above the law.”

In her book, she writes that “the president’s penchant for denigrating other countries has cost America an immense amount of goodwill while boosting the electoral prospects of foreign politicians who express hostility toward Washington and its policies.”

In Santa Cruz, Albright elaborated on this remark: “I think that our strength is the fact that we do have friends and allies, that we don’t have to do everything alone. …We need to know that our national interests are protected better when we are in partnership with other countries so we can share the burdens and do things together … If you look at history, when America is absent, terrible things happen.”

“I think ‘America first’ then becomes ‘America alone,’’’ she said. “I am troubled by the return to the sense that we can be an island. We can’t. I find it stunning that we have managed to make enemies. How can you be an enemy with Canada? What is brilliant about America is we have had two friends on both of our border frontiers.”

Comic relief

Though the conversation matter often drifted towards the somber and the tragic, Albright gracefully accepted an audience member’s question about her famous collection of brooches, which the Smithsonian Castle once exhibited under the title, “Read My Pins.”

Albright used the pins to show admiration and distaste for heads of state, show her priorities to ambassadors, and react to criticisms. When she said “terrible things” about Saddam Hussein for invading Kuwait, and newspapers in Baghdad called Albright “an unparalleled serpent,’’ she wore a brooch shaped like a snake. “I would use it as a diplomatic tool,’’ she explained. “When I was secretary of state, the Russians were bugging the State Department, literally. We complained to Moscow, but when I met with the Russian foreign minister, I wore a huge bug, and he knew exactly what I was talking about.”

Sometimes, Albright assumed the guise of a stand-up comic. When Mendoza called her a feminist icon, but mentioned the noticeable lack of female fascists in Albright’s book, Albright said, “There are not a lot. Frankly, it’s the men. I do believe in women being in power. I am very excited about the women who have just been elected to our Congress. I think there is a lot of hope out there in terms of what they are going to do. But you know, I am asked sometimes, ‘would it be better if the whole world was run by woman?’ If you think so, you’ve forgotten high school.”

She also urged audiences to be proactive, and engage in respectful dialogue, to counter the polarization and the coarsening of political discourse in the United States.

“On my to-do list is to listen to people you disagree with,’’ she said. “I don’t like the word ‘tolerance’ because that means to tolerate, to put up with. It’s more important to respect.”

“I do try really hard,’’ Albright continued. “You should all be very glad you don’t live in Washington, D.C. because I listen to right-wing radio as I drive, and I get very excited about it. Hand gestures and things.”

A former refugee, and lessons from the past

At one point in the talk, Mendoza asked the audience “how many people are here because someone in their past had to flee a government?” Many hands went up. “Right now,” Mendoza continued, “at the Mexican border, there are thousands of people who are being used to stoke fear in the United States.” She was referring to Central Americans who have fled their home countries and seek asylum in the U.S. Turning to Albright, she said, “how does one know when fascism is rising, and it’s time to get the kids and the documents and get out?”

Albright responded with her own vivid story of displacement because of authoritarian regimes.

Born Madeleine Jana Korbelová in Prague, she was forced to flee her home country twice – first, because of the Nazi occupation, and later because of the Communist government. She found out that the United States prided and distinguished itself by opening its arms to refugees.

Albright’s family stayed in England during World War II. Many years later, her father recalled the way the English had treated them. “People were very kind, but they used to say, ‘your country has been taken over by a terrible dictator. What can we do to help, and when are you going home?”

In contrast, “When we came to the United States, people said, ‘we’re so sorry, your country has been taken over by a terrible system. What can we do to help, and when will you become a citizen?”’

That spirit of generosity and openness was on her mind when Albright presented a man with his naturalization certificate during a ceremony on July 4, 2000. “As he walked away, I heard him say, ‘Can you believe it? I am a refugee and I just got my citizenship papers from the Secretary of State!’ So I went up to him and said, ‘Can you believe that the Secretary of State is a refugee?’ That is what the country is about.”

Bookshop Santa Cruz presented the Madeleine Albright event, which was co-sponsored by the Humanities Institute at UC Santa Cruz and Temple Beth El.