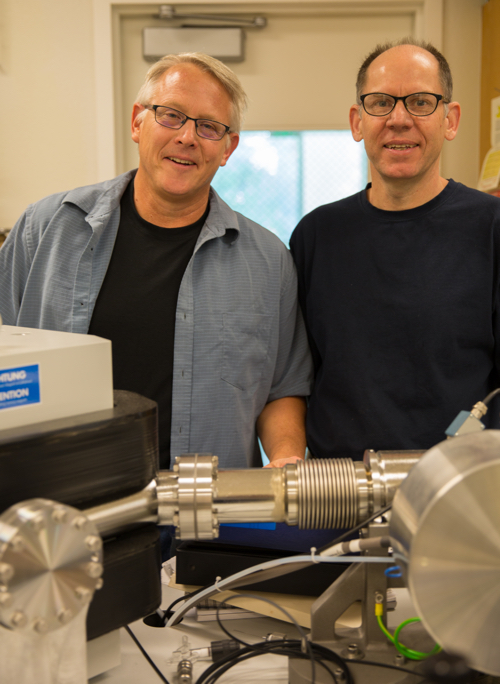

A major grant from the National Science Foundation (NSF) will help fund the acquisition of a new state-of-the-art spectrometer for the Stable Isotope Laboratory at UC Santa Cruz.

The $805,000 project for the new instrument was primarily supported by a $564,184 NSF grant, one of three awards the campus received this year from NSF’s highly competitive Major Research Instrumentation program. In addition, the Office of Research, the Division of Physical and Biological Sciences, the Division of Social Sciences, three departments and a research institute all contributed a total of $241,000 to fully fund the instrument expansion.

Principal investigator Matthew McCarthy, a professor of ocean sciences, said the new equipment will support research across a wide range of disciplines, ranging from oceanography and earth science, paleontology, anthropology, ecology and fundamental biochemical cycle research.

“We want our facility to be a place that diverse scientists from UC Santa Cruz and across our region can use,” McCarthy said. “My vision for this is to be a national and international center for novel and leading-edge stable isotope approaches.”

Powerful tool

Stable isotope analysis is a powerful tool for tracing carbon and nutrients as they cycle through food webs and the environment. UCSC’s Stable Isotope Laboratory, established in 1994, has been one of the world’s top facilities for research on climatic and oceanographic conditions in Earth’s past (paleoclimatology and paleoceanography). Scientists using the lab are at the forefront of research on, for example, ancient greenhouse climates, El Niño Southern Oscillation events, controls on rainfall in California, the vulnerability of species to global change, and other topics. According to McCarthy, research associated with the laboratory has generated over 165 scientific papers since 2004.

Isotopes are different forms of the same element. The most common naturally occurring isotope of carbon, for example, is carbon–12 (the 12 refers to the number of protons and neutrons in the nucleus of the atom). Other carbon isotopes include carbon–14, which is unstable and emits radiation as it decays over time, and carbon–13, which is a stable isotope. While carbon–14 is useful for carbon dating, stable isotopes of carbon, nitrogen, and other elements are useful in a wide range of scientific analyses.

Stable isotopes have proven especially valuable in the analysis of diet, where they can be used to distinguish between different sources of food. Isotopes in the food animals or humans eat are stored in their bones, teeth, and other tissues. By measuring the ratios of certain isotopes in tissue samples, researchers can determine, for example, where an animal fed and whether it ate primarily a marine, terrestrial, or freshwater diet. This ability has made stable isotopes an increasingly invaluable tool for not only ecology, but also paleontology, anthropology, and even forensics.

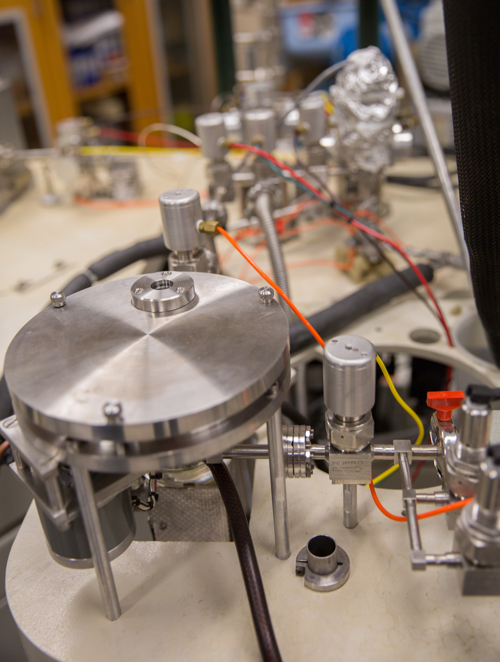

With the new grant, the Stable Isotope Lab will acquire a cutting-edge instrument called an isotope-ratio-monitoring mass spectrometer (IRMS). McCarthy explained that the IRMS is a powerful tool for performing compound-specific isotope analysis (CSIA).

CSIA is a way of measuring isotopes in individual molecules rather than bulk samples, which is the traditional method of stable isotope analysis. This application has proven especially useful for measuring isotope ratios of carbon and nitrogen in amino acids. This type of analysis is a relatively new but very promising field of study that “has exploded in the last 15 years,” McCarthy said.

Innovative research

The new spectrometer will also substantially modernize the existing isotope lab, which was last updated in 2004 and contains still usable but rapidly aging instruments that are now limited in their capabilities. With this new equipment, UC Santa Cruz will continue to be in the forefront of innovative research in the years to come, McCarthy said.

“My vision for this project was really to not just expand things, but to make us a premier, cutting-edge place in the world to do compound-specific isotope analysis across different disciplines,” he said.

CSIA can be used in a broad range of scientific disciplines, including oceanography, biology, ecology, astrobiology, paleontology, Earth science, and environmental studies. One expanding area at UCSC in which CSIA has proven of particular value is in anthropology and archaeology. Traditionally, bulk sample measurement of ratios between carbon–13 and nitrogen–15 in human bone collagen have helped to distinguish diets composed of, for example, animal protein versus plant protein or terrestrial versus marine diets.

Recently, however, it is becoming increasingly clear that this technique is failing to provide adequate data in regions with complex ecosystems where diverse dietary resources are available. Compound-specific isotope analysis of individual amino acids, by contrast, can distinguish these more complex dietary regimes.

Vicky Oelze, assistant professor in biological anthropology, sees great potential for CSIA in her research on the diets and ecology of apes and prehistoric humans. “I want to use the compound-specific approach to answer questions on meat consumption in wild chimpanzees, because the patterns we’re seeing with bulk isotopes are often super confusing,” Oelze said. “If this method works out, we have a much more precise tool we can use for future work on meat consumption frequencies in wild fauna.”

CSIA will also be useful in a number of other areas, such as McCarthy’s research using deep-sea corals to look at millennial-scale oceanographic change. It can be used to investigate biogeochemical cycles, such as how land use changes have impacted nutrient dynamics in coastal and marine habitats, and for other applications such as studying the changes in food web dynamics in modern populations of marine mammals.

If all goes well, the new isotope equipment will be installed and ready for use in standard applications in spring 2019, McCarthy said.

The Stable Isotope Lab in the Earth and Marine Sciences building will be expanded to accommodate the new isotope-ratio-monitoring mass spectrometer. The lab will bring together scientists from different departments, divisions, and regional institutions, and will serve as a training ground for undergraduate and graduate students, as well as visiting researchers.