Campus News

Big ideas

From saving falcons to peering into the universe, sequencing the human genome, and putting organic food on American tables, UC Santa Cruz has become known as the small university where big things happen.

It was May 2000, the race to sequence the human genome was on, and UC Santa Cruz Biomolecular Engineering Professor David Haussler was worried.

A private firm named Celera Genomics was beating a path to the prize with a big budget and what was reported to be the most powerful computer cluster in civilian use.

Meanwhile, an international consortium of public scientists—which Haussler had only recently been invited to join—was lagging behind.

The public institutions assigned to write a program that would assemble the 600,000 fragments of DNA the consortium had decoded into a comprehensible sequence were having trouble. On top of that, the heads of Celera Genomics and the public consortium had agreed to jointly announce the results of their work at the White House on June 26. The deadline was approaching like a speeding bullet.

What happened next was the stuff of movies, and also a reflection of the kind of maverick, can-do ethos that has pervaded UC Santa Cruz for all of its 50-year history.

Haussler, a tall man with a penchant for Hawaiian shirts, managed to wrangle 100 Dell Pentium III processor workstations—each with less power than one of today’s smart phones—and assemble a makeshift “supercomputer.” He then started a behind-the-scenes attempt to write an assembly program. The going was slow, however.

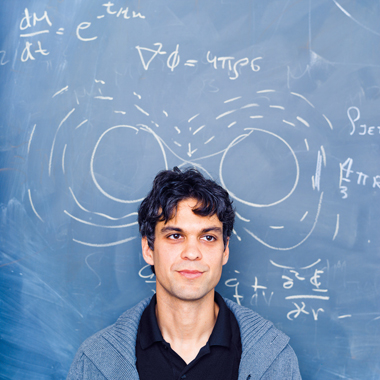

Enter Jim Kent, an unruly-haired UC Santa Cruz graduate student in molecular, cell, and developmental biology. He worried that if a private corporation sequenced the human genome first, thousands of genes might be patented—meaning that, for a time at least, “open science” would have meant “open only to those who could pay.”

On May 22, Kent, who’d cut his coding teeth in the commercial world of paint and animation programming, e-mailed Haussler saying he thought he had found a way to write an assembly program using a simpler strategy.

Haussler replied with one word: “Godspeed.”

“So Jim went for it,” Haussler said. “It was a classic scene. I knew Jim was a genius and I thought, ‘It may be hopeless but, at this point, what have we got to lose?’ Celera had one of the most powerful computer systems at the time, and we, basically, had 100 cell phones.”

Kent spent the next month huddled in the garage office at his Seabright home, writing 10,000 lines of code so furiously and for so many hours, he had to ice his wrists.

On June 22, four days before the White House announcement—and three days before Celera finished its computer assembly—Kent ran the first successful draft sequence of the human genome using the UC Santa Cruz computer farm and 13 sets of data sources.

The announcement of the successful sequencing of the human genome was hailed around the world.

Two weeks later, on July 7, Haussler and Kent had the honor of posting the first human genome on the Internet. In September, they also debuted the UCSC Genome Browser, a graphic web-based “microscope” for exploring the human genome that continues to be free to anyone who wants it.

Today, thousands of biomedical researchers worldwide use the UCSC Genome Browser in their work to uncover the causes of disease and develop treatments. The browser has been mentioned in more than 20,000 different scholarly papers in biomedical literature, an indication of its impact in disease research. The site gets about a million hits per day.

It was an audacious achievement but not the only time UC Santa Cruz has beaten the odds to make a difference. From saving falcons to peering into the universe and putting organic food on American tables, UC Santa Cruz has become known as the small university where big things happen.

Here are just a few examples.

Bring back the birds

Peregrine falcons are the F-16s of nature. They can dive to speeds of up to 300 mph, snatch other birds out of mid-air, and have a ratcheting function in their feet that allows them to lock onto prey and hold it with very little energy.

But by 1970, there were only two breeding pairs left in California thanks to the pesticide DDT, which thinned the shells of the falcons’ eggs, causing them to break under the weight of the nesting adult.

Today, there are nearly 300 productive pairs of the iconic bird, and their return is due in large part to a seat-of-the-pants organization started in 1975 on the UC Santa Cruz campus by the late Natural History Professor Ken Norris.

Like Haussler, the Santa Cruz Predatory Bird Research Group, as it was known, had to MacGyver its way to success. Led by a tireless scientific researcher named Brian Walton, the group sent climbers up rock walls with homemade plywood backpacks to retrieve falcon eggs, which they would replace with fake eggs created by the UC Santa Cruz Art Department.

According to Glenn Stewart, now director of the program, the falcon eggs would then be transported by volunteers to the research group’s makeshift headquarters in the Lower Quarry—which Norris had threatened to power with the “world’s longest extension cord” until administrators agreed to supply electricity to the site. There, the eggs would be hatched in modified chicken incubators and the chicks warmed on heating pads placed in cement-mixing tubs. The birds would be fed with ground pigeon or quail meat raised by staff and volunteers, watched 24/7 by program employees and students, and finally transported back to the nest for their “rebirth,” often to the surprise of their avian parents.

By 1999, the peregrine falcon had recovered enough to be removed from the federal endangered species list.

It was an impudent fight, headquartered on a campus known mostly for its lack of grades, and one that included a lot of improvisation, more than a few bent rules, and even the threat of arrest. (One volunteer was swarmed by a Los Angeles SWAT team while trying to capture pigeons from a freeway billboard in order to supplement the program’s food budget.)

“It’s one of the greatest environmental success stories of all time,” Stewart said.

In a galaxy…

About the same time the peregrine falcon population was taking flight, a group of scientists from UC Santa Cruz were revolutionizing the way we studied the heavens.

Two physicists, Jerry Nelson and Terry Mast, had recently arrived on campus from UC Berkeley. The two had conceived a radical telescope design that used segmented, hexagonal mirrors to peer more deeply into space than ever before. The result was a multimillion-dollar project to build two of these breakthrough 10-meter telescopes on the slopes of Mauna Kea in Hawaii.

In order to work, the telescopes also needed precisely crafted secondary mirrors, and, even though a few outside companies could make them, UC Santa Cruz scientists decided to tackle the difficult assignment themselves.

Then–professor of astronomy Joe Miller remembered: “I said, ‘We’ve got the well-equipped optical laboratory, a very experienced and great optician (Dave Hilyard), and superb support from Jerry Nelson, Terry Mast, and Harland Epps, who is the leading designer of astronomical optics in the U.S.’”

Today, the twin Keck telescopes use secondary mirrors built in a series of unassuming metal-roofed shops amid the redwoods of UC Santa Cruz. The Kecks are considered the most productive telescopes in the world.

Their success also inspired a new effort to build a 30-meter version of the Keck telescopes—an international endeavor with roots still deep in Santa Cruz.

But secondary mirrors were not the only instruments born amid the woods. Instruments conceived by astronomer Steven Vogt and by National Medal of Science winner Sandra Faber have allowed researchers to discover scores of extrasolar planets, find direct evidence for the Hot Big Bang theory, and make major progress in mapping the evolution of the universe for the last 5 billion years.

UC Santa Cruz was also at the vanguard of adaptive optics, technological advances that combat atmospheric distortion so the images scientists see through telescopes are sharp and clear.

“We’ve developed and built these absolutely forefront instruments,” said Michael Bolte, UC Santa Cruz professor of astronomy and astrophysics, sitting in his campus office underneath a photo of one of the Keck telescopes. “The place where it all happened is right here.”

Lights, science, action

Down the hill and a few years earlier, a couple of research biologists and confessed seabird freaks from UC Santa Cruz embarked on a mission that would grow to save 389 species from possible extinction on more than four dozen islands in the world.

It was the 1980s, and Don Croll and Bernie Tershy had loaded up their surfboards and headed to a pair of wind-wracked Mexican islands where feral cats were obliterating Cassin’s Auklets, Scripps’s Murrelets, and Black Storm-petrels.

The men knew what was happening on those specks of land was emblematic of a larger problem: Nowhere were extinctions greater than on the world’s islands, home to 20 percent of bird, reptile, and plant species.

With the help of a legendary bobcat trapper, the determined but underfunded environmental tacticians went to work, managing to clear the islands of the destructive felines. Within five years, the two assembled a rag-tag team of graduate students, trappers, and Mexican conservationists, freeing nine islands off of Baja California of invasive rats, feral cats, rabbits, goats, and burros—allowing native birds and plants to return. They turned the group into a nonprofit called Island Conservation and established its headquarters in a rented space on the UC Santa Cruz marine-lab campus.

Today, Island Conservation is an independent, Santa Cruz–based nonprofit with a $6.5 million budget and projects around the world.

“To us, it was: Why apply science just to describe problems?” Croll said. “Using science to find solutions seemed way more interesting.”

It was a culture born from early faculty like Michael Soulé, a professor of environmental sciences known as the father of modern conservation biology, and the late Ken Norris, a UC Santa Cruz natural history professor who not only helped craft the Marine Mammal Protection Act of 1972 but also co-founded the 756,000-acre UC Natural Reserve System, according to Croll.

Since then, the UC Santa Cruz researchers have helped bring about policy changes like a West Coast ban on fishing for krill, shrimp-like crustaceans that are a major food source for marine life, and are now working with postdoc Asha de Vos to examine a possible modification of shipping lanes that could help save Sri Lankan blue whales. Their students have helped stop construction of a liquefied natural gas plant in an environmentally sensitive area of Mexico and supported modification of rules so oil-spill money for seabird restoration can be used beyond spill boundaries to places the winged victims travel and breed.

“The ethos of this place is to encourage people to go out and do things,” Croll said.

Beyond bars

When Psychology Professor Craig Haney arrived in Santa Cruz in 1977, he’d already witnessed the psychological damage prison could cause.

He had been one of the principal researchers in the famous Stanford Prison Experiment, which had student volunteers playing the roles of guards and inmates in a simulated prison setting, and which had to be halted because of the psychological mistreatment and breakdowns that ensued.

But now Haney found himself in the real world of prisons, talking to inmates in windowless solitary confinement cells where the smells of 23-hour-a-day living and a sense of grief created an almost palpable heaviness in the air.

He witnessed prisoners break under the pressures of isolation and documented how others clung to slivers of humanity by imposing an almost obsessive order on their solitary lives. He saw inmates transition from a fear of being alone to apprehension about being around people, and chronicled the rise of the use of isolation in prisons around the country.

In 2012, he told a U.S. Senate subcommittee that, for many inmates, “solitary confinement precipitates a descent into madness.”

Haney’s four decades of prison research has taken him from frightening prisons in Texas to medieval-looking facilities in Pennsylvania and to a federal supermax prison in Colorado. In California he saw men packed into a sweltering gymnasium with bunks stacked three high as armed guards patrolled catwalks above them.

“Men were living not for weeks or months but for years in these abysmally overcrowded, dangerous, and unhealthy environments,” he said.

In 2011, Haney’s testimony about the psychological effects of this kind of treatment became the cornerstone for a U.S. Supreme Court decision that forced California to reduce its prison populations because of cruel and inhumane conditions.

Sitting in his office in advance of a CNN interview about solitary confinement, Haney reflected on his work both inside and outside the university.

“I think when you see injustices that other people haven’t, it’s important to communicate those observations beyond an academic world,” Haney said. “We have an obligation to share knowledge not just with students but with a larger society. Especially when that knowledge bears directly on things about which the public should know and care about.”

The past is present

If you want to know about climate change, you may want to look deep into the Earth. That’s what Christina Ravelo, UC Santa Cruz professor of ocean sciences, has done, and what she discovered has rattled the way scientists go about predicting the effects of climate shifts.

Ravelo, a paleoclimatologist with a shock of dark, curling hair, has spent countless hours studying sediment cores harvested from deep beneath the ocean in hopes the past would shed clues on the present. Her interest is in an epoch known as the Pliocene Warm Period 3.5 to 4.5 million years ago, when temperatures were a few degrees higher and CO2 levels roughly the same as today.

What she discovered was evidence of a permanent El Niño–like state in the tropics with its resulting drought, floods, and damaging storms. Her discovery shook the scientific community because modern climate-prediction models did not forecast that kind of result.

“The issue has fueled a lot of debate and a lot of scrutiny about how Earth responds to high CO2 levels,” said Ravelo. “There may be even more radical changes that the models aren’t picking up yet because we haven’t been able to simulate a tropical climate accurately. We’re trying to figure out why the models and the data from the Pliocene don’t agree.”

Her findings, along with those made by her colleague Professor of Earth and Planetary Sciences Jim Zachos, and her use of a laser system to analyze the geochemistry of fossils in order to understand climate and ocean dynamics, has put her—and UC Santa Cruz—on the forefront of climate research.

Seed to table

If you’ve ever picked up a carton of organic strawberries from your local supermarket, you have an eccentric English gardener, a passionate farmer/plant ecologist, and UC Santa Cruz to thank.

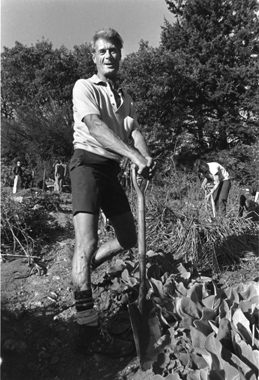

The odyssey of those strawberries began in 1967 when a quirky master gardener named Alan Chadwick arrived at UC Santa Cruz. Tasked with creating a student garden, Chadwick and a host of young acolytes grabbed digging fork and spade, and soon turned a rocky hillside on the upper campus into a garden overflowing with flowers and vegetables. His technique, which he called the French Intensive Biodynamic method, would come to lay the groundwork for organic gardens around the world.

But by 1981, Chadwick had left, and a campus farm born out of that first garden was struggling under a financial drought. Things looked bleak until an enthusiastic plant ecologist and farmer who’d just come from southern Mexico, where he’d worked the soil using traditional farming systems, arrived on campus. His name was Steve Gliessman.

Hired to teach a spring natural history field quarter, Gliessman was also asked to revive the struggling UC Santa Cruz Farm. His idea was to tie the Farm to academics in a science he called agroecology—the application of ecological principles to agriculture as opposed to factory farms’ reliance on chemicals and what he saw as unsustainable practices.

Cobbling funds from philanthropist Alfred Heller and a state program that generated money from custom license plate sales, Gliessman turned the Farm into an outdoor classroom—the first formal academic agroecology program in the world and a program that would also help launch a movement that has changed the way America eats.

As part of the program, Gliessman and students began working with local farmer Jim Cochran in 1985 to study whether organic berry growing could be an economically viable venture.

The answer is evident in the organic produce grown by large-scale farms and sold in the likes of Safeways and Wal-Marts today.

“What we’ve done is call attention, on one hand, to the non-sustainability of the industrial approach to farming,” said the now-retired Gliessman while sitting under the silvery branches of an olive tree he had planted years before at the campus’s Sustainable Living Center. “And, on the other hand, we’ve developed a system of food health and justice from the soil to the people around the table.”

More greatest hits

In addition to the aforementioned big ideas, UC Santa Cruz is responsible for an impressive list of other groundbreaking achievements, including the following.

The Cancer Genomics Hub, built and operated by the UC Santa Cruz Genomics Institute, is an essential resource for scientists studying cancer genomics data with the goal of developing targeted treatments against the disease. CGHub is the largest public database of cancer genome sequences in the world and the first “NIH Trusted Partner” authorized to distribute genome sequence data to biomedical researchers.

By mapping, at the atomic level, the structure of the ribosome, a complex molecular machine found in all cells that translates the DNA molecular machine into functioning proteins, Harry Noller, professor of molecular biology at UC Santa Cruz, and his colleagues have helped provide a basis for the development of targeted antibiotics.

UC Santa Cruz Professor of Anthropology Adrienne Zihlman’s critique of the “Man the Hunter” model changed the idea that male-dominated activities like hunting were responsible for evolutionary adaptations like big brains. Her notion that female gathering activities could just as easily account for these adaptations was responsible for a shift in evolutionary perspective that is now mainstream.

Retired UC Santa Cruz Psychology Professor Elliot Aronson’s work on cognitive dissonance and his invention of the Jigsaw Classroom as a way of reducing ethnic hostility and prejudice in schools resulted in his being listed among the 100 most eminent psychologists of the 20th century.

As leaders in the development of custom electronics and sensors for state-of-the-art particle detection systems, physicists at UC Santa Cruz’s Institute for Particle Physics have been at the forefront of high-energy physics experiments for the past 30 years. Their contributions include a significant role in the discovery of the Higgs boson at CERN, a large part in designing and building the Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope, and ongoing work on upgrades to CERN’s Large Hadron Collider.

Nathaniel Mackey, professor emeritus of literature at UC Santa Cruz, won the Poetry Foundation’s Ruth Lilly Poetry Prize. The $100,000 award goes to a living U.S. poet whose lifetime work warrants extraordinary recognition.

Researchers at UC Santa Cruz pioneered the use of satellite tags to monitor the migrations and habits of elephant seals. Their tags have recorded dives to well over a mile deep and tracked elephant seal migrations throughout the entire northeast Pacific Ocean and as far as the coasts of Japan and Russia.

The renowned Dickens Project began at UC Santa Cruz. A scholarly consortium of members from more than 40 universities around the globe, it is recognized as the premier center for Dickens studies and home to the popular summer Dickens Universe gathering.

Thanks to a high-tech tracking collar developed at UC Santa Cruz, researchers are able to monitor the movements of mountain lions and determine how much energy the big cats use to pounce, stalk, and overpower their prey.

The Jack Baskin School of Engineer-ing started the first undergraduate major in computer game design in the UC system.

In the midst of the 2014 Ebola outbreak in West Africa, the UC Santa Cruz Genomics Institute released a free Ebola genome browser to assist global efforts to develop a vaccine and antiserum to help stop the spread of the disease.

The hows and whys of Earth’s reversals of its magnetic fields can be better understood thanks to a 3D simulation developed by UC Santa Cruz Professor of Earth and Planetary Sciences Gary Glatzmaier. Along with a colleague from UCLA, Glatzmaier created the first computer simulation of the geodynamo in the Earth’s core, which maintains the globe’s magnetic field.

UC Santa Cruz’s Kudela Lab is a leader in understanding the effects of harmful algal blooms on the West Coast. Its founder, Professor of Ocean Sciences Raphael Kudela, is working with the California Department of Public Health to develop better monitoring tools for harmful algal blooms and is developing predictive models for forecasting when and where harmful algal blooms will occur.

In a paper published in Nature, UC Santa Cruz scientists—physicist Joel Primack and astronomers George Blumenthal and Sandra Faber—along with British scientist Martin Rees outlined a theory for the role of Cold Dark Matter in the formation of galaxies. It remains the dominant working paradigm for structure formation in the universe.

In recognition of the important work UC Santa Cruz scientists are doing with data storage and management, industry giants have partnered with the campus to form the UC Santa Cruz Center for Research in Storage Systems.