Using a blend of data, history, and archaeology, UC Santa Cruz undergraduates have explored what life as a slave was like on plantations in the American South. They shared their research findings in an interactive poster session this week.

The presentations are part of the fall quarter class "Slavery in the Atlantic World," co-taught by archeologist and anthropology professor J. Cameron Monroe and history professor Greg O’Malley. This is the second time the professors have taught the course.

Historically, slaves were depicted as only labor and numbers, with very little, if any, information about their personal life. “The history of slavery was written by people in power,” Monroe says.

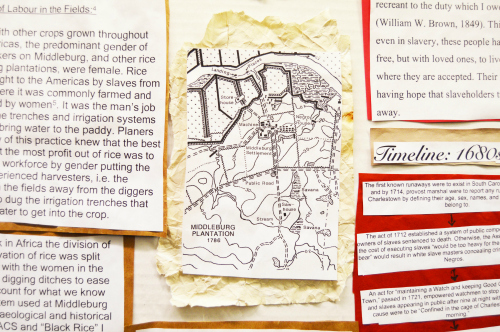

But now with data recently made available by the Digital Archaeological Archive of Comparative Slavery (DAACS) and the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database, students in Monroe and O’Malley’s interdisciplinary class can piece together archaeological records with historical analysis to explore the human side of captive life.

“Now, we can correct the legacy of dehumanizing slavery,” Monroe said about ways an archaeological perspective can complement what these databases can offer. As Monroe and O’Malley share, some scholars see the database as controversial because it reduces slaves’ experiences to numbers, ultimately dehumanizing the slave trade. However, when a qualitative analysis is introduced, students can account for a richer reflection of a slave's lived experience.

As part of his group project, Harrison Sater (Porter ’17, anthropology) examined pottery fragments to better understand material culture in the slave quarters at Thomas Jefferson’s plantation, Monticello, located outside of Charlottesville, Va. His group found there were more earthenware bowls than porcelain plates in kitchens. This indicated to him that slaves ate more soups and stews, typical of their native West African cuisine. This also revealed that slaves were given an illusion of agency to maintain certain cultural traditions in their new life.

But establishing an illusion of autonomy was central for slave owners. Letting slaves think they had certain freedoms was really just another way for plantation owners to control them, says anthropology major Alyssa Robleza (Oakes ’17), whose group studied the ways Jefferson manipulated the environment to convince slaves to not escape at his Virginian retreat at Poplar Forest.

For example, Robleza and her peers followed hedge patterns to show the various ways Jefferson isolated slaves from seeing the external world. By not being able to see outside life, they would not be tempted to escape, says critical race and ethnic studies major Kadijah Means. And because of their insular life, slaves could also form attachments and families, which would also increase their likelihood to stay put.

The groups also used archaeological artifacts to study how slaves might have resisted their captors.

“Ceramics, work material, and bottles of alcohol remains found in these pits show evidence of pilferage,” says Sater.

Students said that the pilfered items in these subfloor pits, special hiding places in slave quarters, were used for planning small revolts.

“Artifacts like sharp bricks and bullets may be evidence of plans for rebellion,” Sater adds.

“Archaeology has the potential to democratize history,” Monroe says.

Other groups looked how the division of labor was split on plantations, how free time could be determined through artifacts, how slaves communicated with slaves at other plantations, and how they actively supplemented dietary rations through hunting.