When Todd Newberry arrived in 1965 to teach biology at the new UC Santa Cruz campus, he stopped at the first important-looking building he saw on High Street. It turned out to be a Congregational Church.

He kept driving, crossing a cattle guard and passing a collection of rundown ranch buildings. "I thought: 'This is it? My God,'" Newberry remembered.

That introduction to the UC system's fledgling university may have been a bit unsettling for the newly hired professor but, in a way, it was also symbolic of what UC Santa Cruz was: an unconventional place that pushed against the stodginess of educational institutions, a place where innovation—no matter how messy—was part of the campus's DNA.

It was, as then-UC President Clark Kerr said, "the most significant educational experiment in the history of the University of California."

Rage against the machine

UC Santa Cruz was born, along with UC Irvine and UC San Diego, as the answer to California's post-war baby boom, which was expected to flood the UC system with 215,000 students by the year 2000—four times the enrollment in 1961.

The campus's location on a scenic sweep of coastal meadow and forest was chosen in March 1961 not only for its staggering beauty but also for its ease of acquisition and the fact its owner, the Cowell Foundation, was willing to donate back a good chunk of the $2 million price tag. The frank and practical Dean McHenry, then UC dean of academic planning, was named chancellor of the new campus a short time later.

Kerr wanted each of the three new campuses to have their own identities and, with his choice of McHenry, cemented the notion that UC Santa Cruz would become a statement against the rise of the large, impersonal, and inflexible university—a concern both men shared.

Using Oxford and Cambridge as their models, the two devised a plan for the new campus: 15-20 semi-autonomous small colleges where students could have close contact with their professors while still being part of a large research institution.

By the time construction began at Santa Cruz, the Free Speech Movement's Mario Savio had famously called upon the 800 protesters occupying UC Berkeley's Sproul Hall to throw their bodies onto the gears and wheels of the university "machine" and grind it to a halt.

That idea of starting an intimate university free of the heavy bonds of bureaucracy and entrenched thought, along with the beauty of the campus, attracted an impressive list of early faculty who had trained at universities like Harvard, Princeton, Yale, Stanford, and Cambridge.

"I was teaching at the University of Connecticut," said John Dizikes, a Harvard-educated professor of history who arrived at UC Santa Cruz for its inaugural year. "Several friends said, "For God's sake, don't go there, you'll end up doing the plumbing." Of course they were right, but what they didn't realize was that it was incredibly exciting to start a place where we were relatively free to do new things."

Among Chancellor McHenry's most important hires were two men who would help set the tone for UC's grand and, what some called "eccentric," venture. Byron Stookey Jr., a quiet and gangly Harvard graduate, was named director of academic planning, and a respected, horseback-riding historian named Page Smith was appointed as Cowell College's first provost.

Together, Stookey and Smith pressed to build a daring intellectual community where learning would become fun and exciting again, where boundaries would be pushed, and what they called "orderly disorder" would rule.

Or as Stookey said: "In order to foster student initiative and individualism, we must institutionalize a tolerance for innovation."

Before classes even began in October 1965, Smith raised the first flag of independence by persuading the new faculty to toss out letter grades in favor of a pass/fail system.

A scruffy utopia

UC Santa Cruz's first 652 students were class presidents, high school newspaper editors, award winners, and valedictorians. Students, the majority of them white, arrived in button-down shirts and pleated skirts having finished a heavy list of required readings: James Joyce's A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, Oscar Lewis's The Children of Sanchez, and Friedrich Nietzsche's On the Genealogy of Morals.

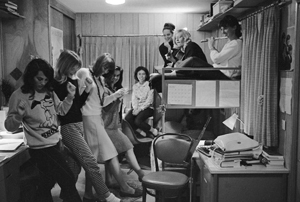

But instead of hallowed halls, what they found were piles of lumber, three buildings that still carried the aroma of putty and paint, and wagon-wheel clusters of 40-foot trailers that would serve as dorm rooms. Cost overruns had delayed construction of the first college, Cowell.

Each trailer housed eight, same-gender students—four at either end with a fake-marble bathroom in the middle. Stuffed with bunk beds, desks, typewriters, clothing, and surfboards, some of the trailers came to look like they were in a perpetual state of ransacking.

Someone dubbed the place, "UC Mobile Home Estates."

"It was like a big summer camp," said Eric Thiermann, who may have been the campus's first entrepreneur, giving $1 haircuts in his trailer—a skill he'd picked up while working in a Kentucky mental hospital.

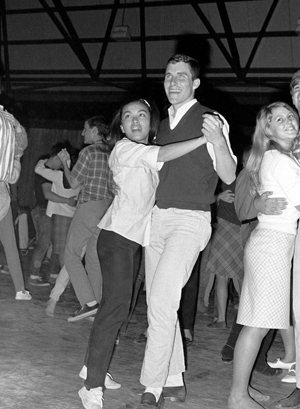

Friendships formed quickly in the cramped quarters. Love blossomed despite rules limiting inter-gender trailer visits. Creative students sent beer cans aloft on firecracker boosters.

But the camp-like atmosphere quickly gave way to the intellectual expectations of the campus's originators. Before classes even started, six professors held an energetic Oxford-style debate in front of the student body on whether On the Genealogy of Morals and A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man misled youth.

Bill Dickinson (Cowell '68, philosophy) recalled being inspired by the rigor of those early readings and of that first debate. "I just remember thinking: 'I'm finally on my way to something important in my life,'" he said.

With only a smattering of buildings, the Field House served as a combination lecture hall, dining hall, gymnasium, study hall, and hangout. Professors, many of them only a few years older than their students, ate with their charges and joined them in games of rugby, baseball, and basketball.

Provost Smith also instituted weekly college nights—completely ignoring a vote of the faculty to hold them only once a month—where students and professors donned formal attire for a dinner followed by a talk or performance from a heady cast of thinkers and artists.

Among those early college night visitors were beat poet Allen Ginsberg, Harvard theologian Harvey Cox, writer/activist Susan Sontag, Scottish filmmaker Alexander Mackendrick, writer Anaïs Nin, and jazz musician Don Ellis.

Dickinson vividly remembered Smith seating him next to Cox during one of those Thursday night dinners because he knew the young scholar was interested in contemporary theological ideas.

"Growing up as I did, in foster homes and an orphanage," Dickinson said, "I was unaccustomed to receiving that sort of respectful attention."

It was at UC Santa Cruz, Dickinson said, that he learned "my life matters."

"Our thesis is simple," said McHenry in a 1966 speech. "In a college setting where a small number of students and faculty go about their daily business in close proximity, it is just that much more difficult to forget that the students are individual, inexchangeable, irreplaceable human beings."

But perhaps nothing pulled the students and faculty closer than the two-year World Civilization core course required of every student on campus.

William Hitchcock, a Yale-educated historian who served with Naval Intelligence during WWII, was to teach the course, which would end with a single, six-hour exam.

His invigorating 9:30 a.m. lectures not only woke up sleepy students but also forced them to devour a reading list of 32 titles, including portions of the Bible. Professors from other disciplines were called on to lead supporting seminars, so a biologist might find himself heading a discussion on ancient Greece. The flamboyant art professor Mary Holmes gave evening slide-show lectures as part of the course.

During that first year, a date might turn out to be a Holmes lecture on Mesopotamian figurines.

"It was such a rite of passage," said Bonita "Bonnie" Banducci (Stevenson '69, sociology). "The heart of the community and the real foundation of our experience was the World Civilization lectures in the Field House," she said.

The course would prove problematic, however, when a full fifth of the class failed the final exam. After an opportunity to re-take the test, 27 letters of dismissal were sent out and administrators got busy redesigning the course.

Audacious and academic

By 1967, Cowell, Stevenson, and Crown colleges had been completed, and the vision of a campus governed by flexibility and experimentation was in full swing. Although at least one student likened the campus to a headless horseman without any kind of obvious direction, most thrived under the system. And, without the burden of grades, students said they felt free to sample new subjects and pursue their passions.

"Because there was so little emphasis on grades, so little emphasis on careers, I think it really opened up people to the possibilities," said Thiermann, whose first taste of photography at UC Santa Cruz would lead him to a career as a filmmaker.

And the campus was rich with possibilities.

Artists like Noah Purifoy, co-founder of the Watts Towers Art Center, and Ruth Asawa, a Japanese-American sculptress and activist, led seminars on campus, while sci-fi author Robert Heinlein showed up, cigarette dangling, to teach a literature class.

With professors also required to teach classes in the colleges, courses like winemaking and American Utopianism were scheduled. Newly hired Earth Sciences Professor Gary Griggs taught a college course titled Shelter, which led students through the process of building a house.

Devoted students flocked to work the soil with Alan Chadwick, a spindly actor-turned-master-gardener who would go on to become a pioneer of organic farming techniques and set the stage for the campus's Center for Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems.

Newberry, already a popular teacher, sent his introductory biology class on a bird walk from the campus to Natural Bridges State Park. The energetic Smith gave his history students tins of snuff to sample and fired a musket out the classroom door while the lumbering but brilliant psychology professor Bert Kaplan's lecture on "The Psychology of Religious Experience" drew packed houses.

"Instead of being totally focused on getting A's, as I had been," said Betsy Buchalter Adler (Cowell '70, psychology), "I focused on learning."

The academic also mixed with the audacious.

One year, four preceptors covered every inch of an empty room underneath the Cowell dining hall with supermarket posters advertising fruits and vegetables. They dubbed it "The Fruit Room" and invited the entire college to a party there—a combination art installation and "happening." A series of sculpture based on poses from the Kama Sutra appeared unannounced on the hills of campus. A human chess game saw Art Professor Holmes riding up on a horse dressed as the red queen, while History Professor Jasper Rose once led the entire World Civilization class in a performance of Handel's Messiah.

Culture Festivals at Cowell College featured Greek costumes, a dramatic reading of Fyodor Dostoyevsky's The Grand Inquisitor, and screenings of the movie Oedipus Rex.

"There were rules, but you didn't necessarily know where all of this was going. You had this clear sense that you, yourself, could chart the curriculum and drop in on classes. You got the feeling part of your education was going to rebound to you as your responsibility. You weren't going to be spoon fed," remembered Jock Reynolds (Stevenson '69, psychology).

A talented athlete, Reynolds had planned to be a marine biologist—until he took a sculpture class from Gurdon Woods, the distinguished former director of the California School of Fine Arts in San Francisco who had been lured to Santa Cruz to lead its fledgling art department.

"You have a fine mind, good eyes, and skilled hands," Woods told Reynolds, as the class progressed. He invited Reynolds to work as his weekend studio assistant and also help establish a small bronze foundry in the old blacksmith shop on campus. During Reynolds's senior year, Woods recruited him and a small group of other willing students to take part in a year-long experimental arts workshop led by the avant-garde Fluxus artist Robert Watts. During this creative adventure, Watts introduced his students to a remarkable array of visiting artists including composer John Cage, choreographer Merce Cunningham, and the father of "happenings" Allan Kaprow.

"This year of constant creative experiences was a transformational one, an educational gift of the rarest kind," Reynolds said.

Reynolds would go on to become a notable artist and director of the Yale University Art Gallery, and, by 1968, UC Santa Cruz had more applicants per opening than any other UC campus, including Berkeley and UCLA.

Times are a changin'

The Vietnam War, the Civil Rights movement, and the sexual revolution were reshaping not only the political landscape of the late '60s but also American culture.

Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert Kennedy had been assassinated. The anti-war movement was growing. Hair was getting longer and skirts were getting shorter. Some 6.5 million American women were on the pill.

At UC Santa Cruz, students were finding their political power.

In 1968, when UC Regents decided to meet on the UCSC campus, 1,000 students, 20 faculty, two horses, and a pig marched from Cowell to Crown College. They were protesting a Regents' decision to bar Black Panther leader Eldridge Cleaver from speaking on campuses and to press for the proposed College 7 to focus on African-American studies and be named after activist Malcolm X. At one point, they rushed then-Gov. Ronald Reagan, who retreated with the help of bodyguards, then returned to talk to protesters. During questioning, he reportedly wagged his finger at a student saying, "Now look here, sonny."

Minority students organized a campus-wide class boycott to protest what they saw as an "irrelevant" education system. An attempt to commandeer a meadow and erect a geodesic dome to serve as a gathering center for student activists ended with arrests and a chilly rainstorm.

But students' dissatisfaction was also balanced with an optimism that they could make change happen and, as students moved from dorms into Santa Cruz, their ideals followed, sometimes to the shock of townspeople.

"UC Santa Cruz was the kind of place that attracted brave and visionary people," said David Talbot (Stevenson '73, sociology), who arrived on campus in 1969. The journalist, who would go on to found Salon.com and write a book about the Kennedy brothers, remembered living in a downtown Victorian with a group of eight feminists from campus.

They started a food co-op and a women's health clinic in Santa Cruz and organized war protests and guerilla theater that landed Talbot in jail on more than one occasion. They gathered UC Santa Cruz students to go into prisons to teach.

"This ferment of creativity that was about imagining a new world was inspired by Santa Cruz," Talbot said.

But change wasn't only about politics.

By the late '60s, plans were already under way for the formation of what would become UC Santa Cruz's Institute of Marine Sciences. J. Herman Blake, the campus's only African American professor, was helping guide the proposed College 7 (now Oakes College) toward an emphasis on ethnic studies. The bearded molecular biologist Harry Noller had also begun his pioneering work on the ribosome, a complex molecular machine found in all cells that translates genetic code into functioning proteins.

"The ivory-tower atmosphere and relative isolation of UCSC were in a way liberating," Noller said in an article about his career. "There were not a lot of 'experts' around to discourage you from going in unusual directions."

For many of those who arrived in 1965, their 1969 graduation would include disgruntled students throwing their diplomas at Kerr and McHenry, and a noisy guerilla theater performance in which activist students conferred an honorary degree on the imprisoned Black Panther leader Huey Newton.

By then, much had changed from the innocence of those trailer days and yet much had stayed the same. With graduation, the bright, young pioneers walked into the world armed not only with their idealism and curiosity, but also with a set of critical thinking skills and the knowledge they had gathered while in the company of friends.

The UC Santa Cruz experiment "worked very beautifully and very surprisingly," said Art Torres (Stevenson '68, government), who would go on to serve eight years as a California assemblyman and 12 years as a state senator, and is now vice-chair on the governing board of the California Institute of Regenerative Medicine.

"It was," he said, "a very magical place."