Campus News

Study of mountain lion energetics shows the power of the pounce

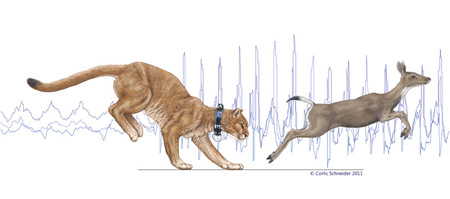

High-tech collars enabled scientists to track mountain lions in the wild and determine how much energy the big cats use to hunt their prey.

Scientists at UC Santa Cruz, using a new wildlife tracking collar they developed, were able to continuously monitor the movements of mountain lions in the wild and determine how much energy the big cats use to stalk, pounce, and overpower their prey.

The research team’s findings, published October 3 in Science, help explain why most cats use a “stalk and pounce” hunting strategy. The new “SMART” wildlife collar–equipped with GPS, accelerometers, and other high-tech features–tells researchers not just where an animal is but what it is doing and how much its activities “cost” in terms of energy expenditure.

“What’s really exciting is that we can now say, here’s the cost of being a mountain lion in the wild and what they need in terms of calories to live in this environment,” said first author Terrie Williams, a professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at UC Santa Cruz. “Understanding the energetics of wild animals moving in complex environments is valuable information for developing better wildlife management plans.”

The researchers were able to quantify, for example, the high energetic costs of traveling over rugged terrain compared to the low cost of “cryptic” hunting behaviors such as sit-and-wait or stalk-and-ambush movements. During the actual pounce and kill, the cats invest a lot of energy in a short time to overpower their prey. Data from the collars showed that mountain lions adjust the amount of energy they put into the initial pounce to account for the size of their prey.

“They know how big a pounce they need to bring down prey that are much bigger than themselves, like a full-grown buck, and they’ll use a much smaller pounce for a fawn,” Williams said.

Cats on treadmills

Before Williams and her team could interpret the data from collars deployed on wild mountain lions, however, they first had to perform calibration studies with mountain lions in captivity. This meant, among other things, training mountain lions to walk and run on a treadmill and measuring their oxygen consumption at different activity levels. Those studies took a bit longer than planned.

“People just didn’t believe you could get a mountain lion on a treadmill, and it took me three years to find a facility that was willing to try,” Williams said.

Finally, she met Lisa Wolfe, a veterinarian with Colorado Parks and Wildlife, who had three captive mountain lions (siblings whose mother had been killed by a hunter) at a research facility near Fort Collins, Colorado. After eight months of training by Wolfe, the mountain lions were comfortable on the treadmill and Williams started collecting data.

Power animals