Campus News

Virtual anthropology uses digital copies to increase access for students

The trouble with working with bone fragments in an anthropology lab is they’re often fragile and always one of a kind. What if you could create identical copies, enough for each student?

The trouble with working with bone fragments in an anthropology lab is they’re often fragile and always one of a kind.

What if you could create identical copies, enough for each student? That’s exactly what UC Santa Cruz anthropology professor Alison Galloway is doing with her extensive bone collection.

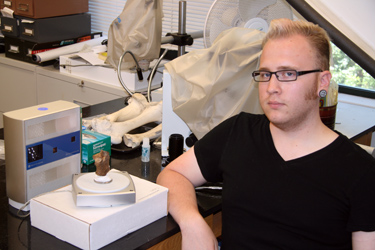

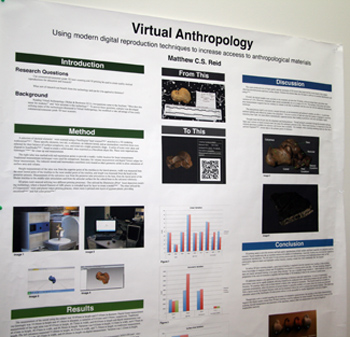

One of Galloway’s past undergraduate students came up with the idea. Matthew C.S. Reid, who graduated a year ago, spent the past summer scanning Galloway’s collection and “printing” 3-D copies of each of the more than 400 samples.

Reid took Galloway’s skeletal biology class in winter quarter 2011 when he got to thinking about how to make the bone fragments available to students. “I wanted to improve education for people like me,” he remembers.

“Bone fragments are pretty fragile, we can’t let students handle them,” Galloway says. But the study of forensic anthropology requires students and researchers to see how fragments fit together. Recreating, for instance, what a skull looked like before it was struck with a blow or bullet.

Galloway said her forensic work sometimes requires gluing pieces together. Even that process changes the pieces. “We lose what’s on the fragmented surface,” she said.

Reid had transferred from Laney College in Oakland with a dual interest in anthropology and computers – particularly 3-D modeling. Both interests came into play with what he calls “virtual anthropology. “It’s the perfect marriage of osteology – the study of bones –and computers,” he said.

Reid and Galloway secured funding for the project this summer to scan and digitize the collection. The resulting ones and zeros create a variety of opportunities, Reid said. The optical scanner “shoots lasers and science comes out,” he said.

The process is tedious using a 3-D scanner connected to a Dell workstation. A heel bone might take a half hour to scan; a skull several hours. But the digital data allow for an infinite supply of precise, inexpensive three-dimensional copies, giving each student in subsequent classes a sample to study, work with, and even alter or destroy.

“This way we can retain the original,” said Galloway, who is also UCSC campus provost and executive vice chancellor. She is often called to testify in criminal cases. “We can do reconstruction on a print; we have the original and the print – both are available to the defense and prosecuting counsel in the case of a trial.

UC Santa Cruz is one of the first universities in the U.S. to use the scanning and 3-D print technology to copy a anthropology collection. Galloway and Reid plan to make the information open source, posting it on the web so that other institutions and researchers can use it and even make copies of their own.

Reid, who plans to apply to graduate school to further his work with 3-D scanning, is particularly interested in other data the technology allows. He’s able to calculate highly accurate surface area and volume from the digitized samples, data that are practically impossible to measure otherwise.

Once Galloway’s collection is cataloged digitally, Reid will move on to other collections.

Galloway said she is happy with the project. “I was interested in having a library of images that students could use in the classroom. He was interested in the 3-D imaging. In an odd coincidence, two people came together with interests that meshed.”

“This is so cutting-edge,” Reid said, “and UC Santa Cruz is doing it.”