Campus News

Teaching the teachers

UC Santa Cruz serves California through Cal Teach, a program that encourages and prepares math and science students to become teachers.

For Monica Villarón, the second Monday of August was one of the most exhilarating and stomach-churning days a person can have in a career. It was her first day as a high school math teacher, the first day she stood on her own in front of eager, indifferent, bored, or hyperactive students expecting her to have all the answers.

“I was excited and nervous,” she said the day after she started teaching at Ceiba College Preparatory Academy in Watsonville. “I tried to form a relationship with the kids, but also set my rules for the rest of the year. By the end of the day, I was exhausted.”

There’s no escaping all the jitters and mistakes of a teacher’s rookie year, but Villarón has an edge over most first-year educators: the experience she gained in the Cal Teach program at UC Santa Cruz.

“Cal Teach gave me my first experience working with kids, so I feel I was able to learn how to connect with kids and became efficient at explaining things,” the 2011 graduate said, also noting the importance of traditional student teaching. “This will be my first year, but I feel prepared.”

Turning students into teachers

Preparing talented math and science students to become secondary-level teachers is the mission of Cal Teach, a statewide initiative launched in 2005 in response to a chronic shortage of highly qualified teachers in subjects so critical to economic competitiveness and to understanding and resolving complex modern problems.

“Often science and math majors who are the most knowledgeable and excited about the subjects are not going into teaching,” said Kim Newman, coordinator of the P20 Partnerships Teaching Leadership initiative in the UC Office of the President. (P20 refers to the path from preschool to grad school.) “Being taught by non-math and science majors is reflected in the test scores of students and the number of young kids who are actually interested in math and science.”

While there are many factors that play into low test scores, the results locally and statewide are disheartening. In Santa Cruz County, only 20 percent of 9th grade students passed the basic math exam while 49 percent of 10th graders passed the science test, according to the 2011 STAR test results. Statewide, those numbers are 18 percent and50 percent, respectively.

Typically, prospective teachers complete an undergraduate degree and then pursue the credential required to teach in California classrooms before getting their first taste of commanding a classroom.

High school graduates who know they want to teach usually attend one of the California State University campuses, but the UC system has the most science and math undergraduates in California, making it a fruitful hunting ground for future science and math teachers who may think they’re headed for a lab instead of a classroom.

“We’re open to anyone who’s willing to explore the possibility of being a teacher,” said Gretchen Andreasen, a director of Cal Teach at UC Santa Cruz. “Our undergraduate program doesn’t replace what students do in a teaching credential program, but it gives them a clear sense of whether they may like teaching.”

Cal Teach at UC Santa Cruz is a freestanding program working in collaboration with several established departments (education, math, physics, biology, and Earth and planetary sciences) and schools throughout Santa Cruz County.

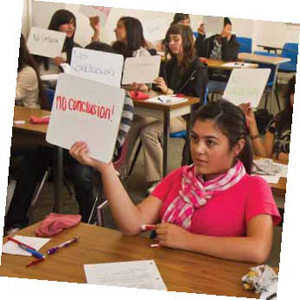

That makes it risk-free for undergrads, who can test out the idea of being a teacher without straying off the pathway of their major. It also makes it effective because students are immediately in classrooms with real kids, learning about classroom management, lesson plans, and meeting the needs of diverse students.

Cal Teachers in classrooms

It’s far too soon to truly measure the impact of the program, but five years after Cal Teach launched, its first graduates are teaching and inspiring students up and down the state, including more than 15 in classrooms in Santa Cruz, Monterey, and San Benito counties.

“They’re really starting to make a difference as strong candidates for our school districts,” Andreasen said. “One of the things that makes me proud and happy is how delighted Santa Cruz City Schools is with our students whom they’ve hired in the past couple years.”

Cal Teach graduates show up the first day with “great depth of learning,” said Karen Hendricks, the assistant superintendent for human resources for the Santa Cruz district.

“They are prepared to engage students in rigorous and relevant curriculum and be very valuable members of our collaborative learning community,” she said. “The best package is one who has strong content knowledge and knows how to interact with students, parents, and colleagues. Students coming out of Cal Teach are very adept at those things.”

Cal Teach students start with classes in pedagogy, some of which are taught by secondary teachers, and a series of progressively intensive internships, starting with 25 hours in the classroom of a host teacher.

In five years, nearly 2,000 students statewide and 349 students at UC Santa Cruz have enrolled in at least one Cal Teach internship. Of those Santa Cruz students, 224 have graduated, and Cal Teach staff believe 73 have gone on to pursue a teaching credential.

That’s 73 new math and science teachers who otherwise might be doing something else, who might never have heard the call, for example, to serve English languagelearners in South Santa Cruz County.

Villarón grew up in Watsonville. She considered other career paths in college but in Cal Teach discovered education is her passion, through activities like teaching a calculus lesson in Spanish. She even turned down a research fellowship in order to take the teaching job at Ceiba.

“It was very humbling to realize the struggle English-language learners face in our classrooms,” she said. “At the end of the day I knew that my calling was to help underrepresented minorities join the math, science, and engineering fields, and teaching was the perfect avenue to do so.”

Watsonville High math teacher Vivian Moutafian taught Villarón in high school and in Cal Teach and calls her a “star student.”

“Monica is born to teach,” she said. “She’s hardworking and articulate, and she really cares about the students. She’s got everything it takes.”

Moutafian should know. She’s been teaching for more than 30 years and has seen hundreds of young teachers.

“There’s a huge turnover in new teachers,” she said. “They often experience burnout. Cal Teach gives prospective teachers an opportunity to see firsthand what it means to teach and the support of their host teachers and Cal Teach instructors. I think we’ll keep more high-quality teachers this way.”

Matt King is a freelance writer based in San Jose.

This article appears in the fall 2011 issue of Review magazine.