Campus News

Uncommon people / Judy Yung: Angel Island Centennial teaches important lessons

At 100, the “Ellis Island of the West” shows us that immigration reform is needed now.

January 21, 2010, marked the centennial of the Angel Island Immigration Station, popularly known as the “Ellis Island of the West.” But to the thousands of Chinese immigrants who were detained there for weeks and months to undergo harsh examinations, and to appeal exclusion decisions, Angel Island was nothing more than a prison.

This place is called an island of immortals,

When, in fact, this mountain wilderness is a prison.

Once you see the open net, why throw yourself in?

It is only because of empty pockets I can do nothing else.

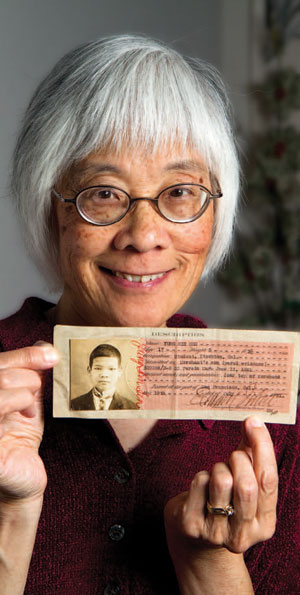

This Chinese poem that was found carved into the immigration barrack walls remind us that unlike Ellis Island, which restricted but did not exclude European immigrants to this country, Angel Island was built specifically to enforce the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, to keep Chinese laborers out of the country. The first racial group to be excluded by U.S. law, Chinese like my own father, Tom Yip Jing, were the first “illegal immigrants.” To circumvent the exclusion laws, he assumed a false identity. Once admitted into the country, my father had to live a life of deceit and duplicity, under constant fear of deportation.

Today, immigration is still a complicated and contentious matter, as we debate over who to let in and who to keep out, and what to do with the 11 million undocumented immigrants in the country. Last April, Arizona passed the toughest immigration law in decades, authorizing local police to arrest and detain suspected “illegal immigrants” and requiring aliens to carry immigration documents with them at all times.

How does this anti-immigrant trend jibe with the popular view of America as a “nation of immigrants” that welcomes “the tired, the poor, the huddled masses yearning to breathe free?” The Angel Island story tells us that the United States has always had a complicated relationship with immigration, including some and excluding others. While many Asian immigrants were denied entry at Angel Island because of race- and class-biased exclusion laws, thousands of newcomers from Asian, European, and Latin American countries were admitted, allowed to settle and eventually become U.S. citizens. Like other immigrants before them, they went on to help make America the powerful and rich country it is today.

In 1965, Congress passed new immigration legislation that put every race and nation on an equal footing. However, years of lax enforcement of our immigration laws, backlogs and bureaucracy, and inadequate work visas to meet the needs of a global economy have resulted in a vast population of undocumented immigrants, all forced to live in the shadows.

As we commemorate the 100th anniversary of the Angel Island Immigration Station, let us remember its multiracial history of inclusion and exclusion. Discriminatory and unfair immigration laws have harsh and deep repercussions on the lives of people. Conversely, fair immigration policies that uphold our values as a nation of immigrants have led to beneficial gains for the entire society.

More than ever before, our country needs comprehensive immigration reform that will secure our borders, benefit our economy, and provide a pathway to responsible citizenship for those undocumented immigrants who deserve it.

Judy Yung is a professor emerita of American studies. She co-authored Angel Island: Immigrant Gateway to America with historian Erika Lee.