Campus News

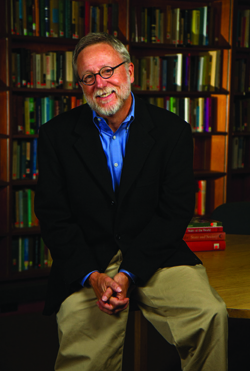

Alumni in Profile / Gregg Herken — Unraveling history’s mysteries

Gregg Herken, a member of UCSC’s pioneer class, brought some of the Cold War’s secret weapons into public view.

It sounds like the plot of a Cold War novel: delicate negotiations with the Soviet military, clandestine satellite recovery, the unmasking of a secret Communist in the highest branches of science.

Instead, it’s part of the life story of Gregg Herken, a retired professor of history at UC Merced and a member of UC Santa Cruz’s first graduating class (Stevenson ’69; history, politics).

Herken borrowed the motto of Cowell College, UCSC’s founding college—“the pursuit of truth in the company of friends”—and carried it into his professional life. Herken looked for the truth in some of the mysteries of history, and brought secret weapons of the Cold War into the public view.

Herken made his most publicized discovery while researching his book, Brotherhood of the Bomb, a finalist for the Los Angeles Times Book Prize in history in 2003. While exploring the lives of the three creators of the nuclear bomb—Robert Oppenheimer, Ernest Lawrence, and Edward Teller—Herken uncovered something Oppenheimer had tried to hide for years. Despite his denials, Oppenheimer had once been a member of a closed unit of the Communist Party.

But was he a spy for the Soviets?” says Herken. “Categorically, absolutely not.

Now Herken has turned his research focus toward three men who played pivotal roles in the Cold War: columnist Joe Alsop, Washington Post owner Philip Graham, and head of covert operations for the CIA Frank Wisner.

“They got together every Sunday for supper and, basically, they ran the country from those meetings,” Herken says. His book about “The Georgetown Set,” scheduled for publication in 2016, promises an in-depth look at this powerful group and the answer to another mystery: Who tried to blackmail one of those men?

Herken’s pursuit of truth also came into play in his role as chairman of the Department of Space History at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Air and Space Museum.

During his 15-year tenure, Herken obtained a top-secret U.S. spy satellite that the government refused to admit even existed at first, and also acquired one of the Cold War’s most notorious missiles, the Soviet SS-20, for the museum. The latter deal required long negotiations with the Soviet military, three trips to the U.S.S.R., and a last-minute flurry of talks when the missile was unveiled with a very unhistoric “SS-20” the Soviets had painted in huge, celebratory red, white, and blue letters on its side.

Herken smiles when he remembers the way his jaw dropped in reaction to the altered missile. But visitors to the Air and Space Museum will only see the results of Herken’s negotiations: a discreet Cyrillic U.S.S.R. on the 55-foot-tall weapon.